Should an artist’s behavior change how we see his work? I have a hard time tolerating the work of Pablo Picasso, because I sense his misogyny shining through his work. Paul Gauguin, it has been argued, was merely following Polynesian culture in his sexual relationships with teenaged Tahitian girls. I think that’s a terribly abusive, colonialist mindset.

The question of art and morality came to mind this week with the passing of Pope Francis.

Fr. Marko Rupnik has evaded justice for six years for documented sexual abuse of nuns. The appointment of his canonical judges, ironically, coincided with the death of Francis, who some critics accused of protecting Rupnik. (Francis later lifted the statute of limitations so Rupnik could be tried, so it’s complicated.) Hopefully, the trial won’t be forgotten in the current crisis in the Holy See.

What does this have to do with art?

Besides being a priest, Marko Rupnik is an artist whose mosaics and other art grace many Catholic churches, chapels, and shrines around the world. They’re not my cup of tea; to me they look derivative and expensive. But someone must have liked them or they wouldn’t be everywhere. Given that the Vatican has already determined that Rupnik did, in fact, abuse these sisters, what are those sanctuaries going to do with those monstrously large mosaics?

That’s a timeless question, and it relates to that which we also have to answer any time we look at art by a disturbed or disturbing individual. It’s a question that sits at the intersection of art, ethics, and personal values.

The aesthetic autonomy argument

Some argue that once a work is created, it stands alone. The artist’s personal behavior, no matter how flawed, shouldn’t affect how we interpret or value the work. This view emphasizes the art itself—its technique, message, emotional impact—over the biography behind it.

That’s easier to do when more time has elapsed. Very few of us, for example, know anything about the personal life of, say, Benvenuto Cellini, but we can recite chapter and verse about Taylor Swift.

Context

We could argue that Caravaggio’s propensity for violence (after all, he killed a man in a brawl) is a lens through which we understand the gritty realism of his work. He was also systematically ripped off by his putative patrons, the Borgheses. Edgar Degas’ antisemitism, while reprehensible, was sadly in line with popular sentiment in late 19th century France. There are situations where context doesn’t excuse behavior, but it does make it more understandable.

Our own ethics as viewers

We make ethical choices every time we buy something, and art is no exception.

That is magnified in the case of Rupnik, whose art is in places of worship worldwide. I’m not Catholic but I like what Bishop Jean-Marc Micas of Tarbes and Lourdes, France, said about it:

“My role is to ensure that the Sanctuary welcomes everyone, and especially those who suffer, among them, victims of abuse and sexual assault, children and adults.

“In Lourdes the tried and wounded people who need consolation and reparation must hold first place.”

My Tuesday class is sold out, but there’s still room in the Monday evening class:

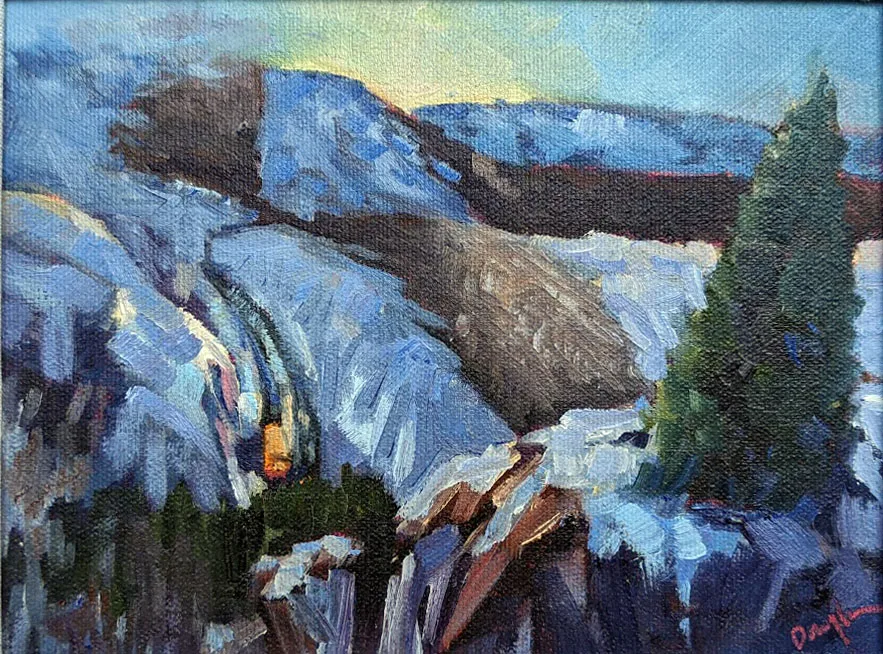

Zoom Class: Advance your painting skills

Mondays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 28 to June 9

Advance your skills in oils, watercolor, gouache, acrylics and pastels with guided exercises in design, composition and execution.

This Zoom class not only has tailored instruction, it provides a supportive community where students share work and get positive feedback in an encouraging and collaborative space.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.