‘What is art?’ is a deceptively simple question. I come down hard on the argument that art is any creative impulse that is utterly useless in practical terms. Art is created primarily for aesthetic, intellectual or expressive purposes. It evokes emotions, conveys ideas and, hopefully, provokes thought.

Craft, on the other hand, is traditionally used to describe work that serves a practical purpose. Of course, the line between art and craft is hopelessly vague and jagged. There was no legitimate purpose served by the exquisite illumination of the Lindisfarne Gospels; the stories were read out to an audience who probably couldn’t read and never had a chance to look at the pictures. The illumination was just a celebration of the magnificence of the Good News. But we call those unknown artists ‘medieval craftsmen.’

In late medieval Europe, tapestry was the central, most expensive figurative medium. Tapestries often showed complicated Biblical, allegorical or historical scenes. They were full of beautifully drawn figures in well-drafted settings.

These immense wall hangings were made in large workshops under the aegis of a master artist. Their production was not materially different from the painting workshops that would follow in the Renaissance. However, tapestry was based on two very practical crafts, weaving and needlework. We’ve further muddied the waters by assuming that the magnificent tapestries of our ancestors were primarily to keep drafts down. We call tapestry a craft, even though its technical demands are at least equal to those of painting.

Hans Holbein traipsed all over Europe to paint portraits of prospective brides for Henry VIII. (The king was terribly disappointed in Anne of Cleves when he saw her in the flesh, so much that the marriage was unconsummated. But he was the only person who thought her homely, so we’ll never know if Holbein flattered her or if Henry was unreasonable.)

Holbein’s paintings were made for a highly practical application, but they’re among the great paintings of the western canon. Nobody would call them craft.

Consider three tiny figurines, exactly the same. The first was made as a doll for a child. It’s by our modern lights a craft object. The second was made to cast a spell upon an unlucky recipient. That’s also a craft object. The third was made for no reason other than that its maker thought it was a good idea. That’s an art object.

I may not like a Maurizio Cattelan‘s Comedian (the infamous banana taped to a wall) but it provoked a response and a lot of conversation. That’s one of the fundamental purposes of art. Could I have enraged as many people with a landscape painting? Hardly.

A large part of the game Warhammer 40,000 is painting miniatures. Is that a craft, because it’s for a game, or art, because it’s totally useless? Is building a model of Frederic Church‘s Olana in The Sims, as my daft daughter is doing, art or craft?

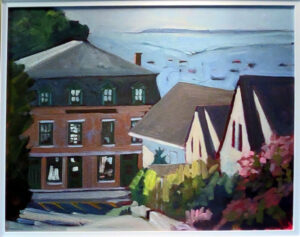

I’ve spent a few weeks at the Red Barn Gallery in Port Clyde contemplating a vivid and sublime Eric Jacobsen painting. It has been a true aesthetic pleasure. Beauty is something both traditional art and craft do magnificently. It’s something a banana taped to the wall (and much other modern art) fail at. To divorce aesthetics from art is as foolish as trying to draw a line between art and craft.

Speaking of the Red Barn Gallery, intake for the annual 10X10 show starts this Thursday. It’s a juried show that runs from August 11-September 1. Artists can submit up to three works, and the fee is $15/per submission. The application form is here.

I’ll be there on Thursday, and I’d love to see you!

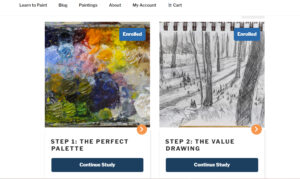

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.