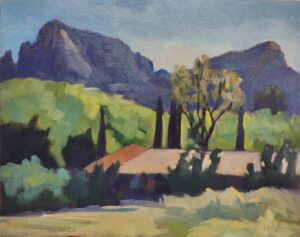

Occasionally, I’ll hear someone fumble for a description of a painting and come up with plein air style. Plein air isn’t a style or technique; it simply means painting outdoors instead of in a studio. Plein air allows an artist to capture natural light and colors from direct observation, and it’s a very important movement in art history, starting with John Constable and still popular today.

What these people are groping for is the term alla prima. The confusion lies in the fact that most (although not all) plein air painters also use alla prima technique.

What is alla prima?

Alla prima (also called au premier coup, wet-on-wet, or direct painting) is a technique where the artist applies paint directly onto the canvas without letting earlier layers dry. This contrasts with indirect painting, which I describe below.

Alla prima is used mostly in oil painting, but it has its equivalent in wet-on-wet watercolor. In alla prima painting, the artist strives for fast, incisive brushwork. It requires skill to avoid making mud, and the artist must work with confidence and speed.

Alla prima has been in use since the Early Netherlandish painters. It became popularized with the rise of Impressionism, but painters as disparate as Frans Hals, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, John Singer Sargent, Chaïm Soutine and Willem de Kooning have all painted directly. Rembrandt van Rijn painted indirectly for the most part, but pointed up his work with alla prima passages.

Alla prima paintings are not necessarily completed in one session, although the goal is to not let the bottom layers dry before adding more paint. There is minimal layering, and the focus is on capturing the essence of the subject with bold, confident strokes. It prioritizes expression and immediacy over meticulous detail.

This lends itself to a more expressive, loose style, with visible brushstrokes and a sense of movement. In fact, when people tell me their goal is to ‘get looser,’ what they generally mean is that they want to master alla prima painting.

Indirect painting

Before we had oil painting, we had egg tempera, encaustic, fresco and distemper, none of which lend themselves to bravura brushwork. It’s no surprise, then, that meticulous, detailed painting was the first form oil painting took. Just as tempera is layered, so was early oil painting.

In indirect painting, the artist builds up the image with transparent layers. Each layer dries completely before the next one is applied. Indirect painting allows for a high level of control and detail. Artists can build up subtle transitions of color and light, creating a realistic, highly polished finish. Indirect painting’s great virtue is that it creates luminosity that’s impossible to achieve with direct painting. That comes, however, at the expense of brilliant color and brushwork.

Indirect paintings start with a monochromatic underpainting or grisaille: While most direct painters do this as well, the grisaille in an indirect painting is intended to show through subsequent layers. This establishes the composition and tonal values retained throughout the piece.

This base layer is allowed to dry and is followed with diluted, transparent layers of paint (called glazes). These are applied over the underpainting to modify the color. Each glaze layer dries before the next is added. White is lousy for glazing, so in a well-painted indirect painting, the light is reflecting through the paint from the grisaille layer.

Indirect painting was widely used during the Renaissance and Baroque periods. (It’s the only way to achieve true chiaroscuro.) There are artists using it today, but they’re doing so almost self-consciously, as a throwback to earlier periods in painting history.

Back in the last millennium, I learned indirect painting first, alla prima second. (Rembrandt’s style was undergoing a miniature renaissance then.) Today, there are far more modern painters pursuing alla prima than indirect painting, but one isn’t inherently better than the other. In fact, with new materials solving the age-old problems of chroma and cracking, who knows if indirect painting is due for a rebirth?

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.