Muncho Lake is surrounded by the high, barren peaks of the Muskwa Ranges and the Sentinel Range, which reach altitudes of more than 6,600 ft. Since the lake is about 3000 feet lower, the jutting mountains against the water are both beautiful and terrifying.

The lake is, in some lights, jade-green in color due to copper oxide leaching from the bedrock. On this day it was tinged with the rock flour that is found in glacial streams. “Glacial milk,” as this water is called, can be milk chocolate brown, ivory, or turquoise. The rock flour itself is made of fine-grained particles ground off bedrock by glacial erosion. Because the silt is so fine, it ends up suspended in glacial meltwater.

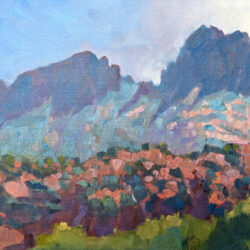

There’s a tiny community at Muncho Lake, but it isn’t much more than a service station. We passed without stopping, because neither of us was feeling well. By the time we arrived at Toad River, Mary was feverish. I just had a nasty cold, so I left her sleeping in a room at the Toad River Lodge and headed back to Muncho Lake to paint.

I returned to Toad River in the early evening to find that Mary still hadn’t stirred. I felt her head; she was hot to the touch. Clearly, there was something more seriously wrong than a bad cold. At this point, my husband took over as our long-distance logistician. He has us moving in slow stages over the next few days so that she could rest and recover—and above all, not camp. It was way too cold.

Even better, there was a clinic in Fort Nelson. She saw a doctor, and it turned out that she had mononucleosis.

—

In 2016, my daughter Mary and I set off across Alaska and Canada on a Great White North Adventure, which you can read about starting here. We arrived in Anchorage at the beginning of September and got home in mid-October. In between, we visited every province but PEI (been there, done that), and Yukon Territory. In retrospect, it might have made more sense to do this during the summer, since Alaska and Canada threw a mess of strange weather at us.