|

| Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man was based on book III of De Architectura. Vitruvius said the human figure was the principal source of proportion for the classical orders of architecture. |

The art of hydraulic cement was lost after the fall of the Roman Empire and not rediscovered until 1756, but if people had just read their Vitruvius, the recipes were in there all along.

Sandy Quang (who is writing her Master’s thesis) prefers her Vitruvius aloud so I’ve listened to quite a bit of his De architectura in recent months. He’s such a lucid writer that I have no trouble following it while driving. What’s amazing is how much of what he describes hasn’t changed in almost 2100 years.

|

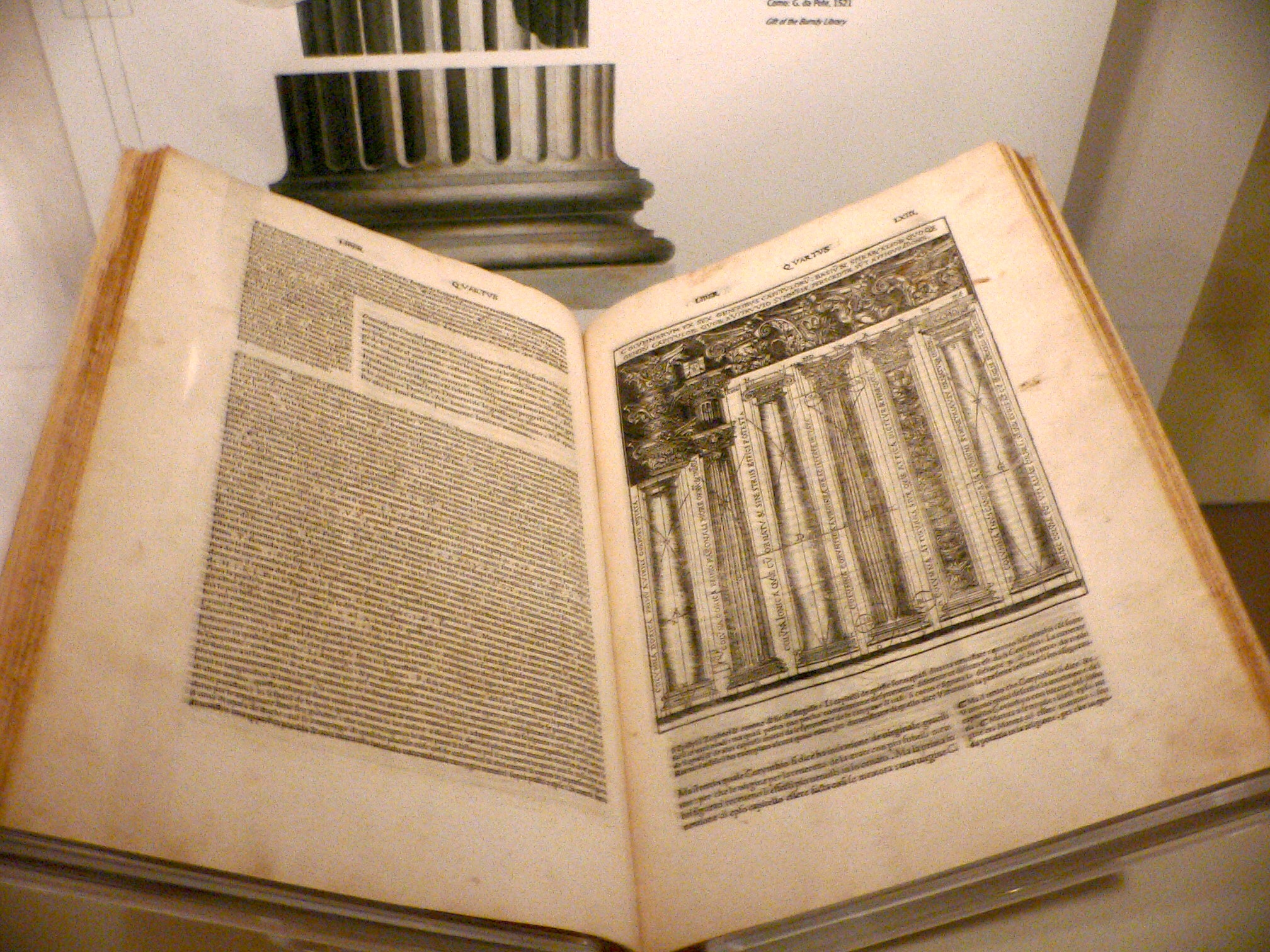

| 1521 edition of De architectura, translated and illustrated by Cesare Cesariano |

Very little is known about Vitruvius’ life. He was born about 80–70 BC and died sometime after 15 BC. He was some kind of praefect, but whether that was in the army or civilian life is not clear. He was mentioned by Pliny the Elder and Frontinus, but even his cognomen (surname) and first names are uncertain.

What an amazing mind Vitruvius had! He not only wrote; he practiced his craft. As an army engineer he specialized in the construction of ballista and artillery. He described the building methods of foreign tribes throughout the Roman Empire, from which it can be inferred that his service was broad. And somehow, he had the time to write this ten-volume treatise on architecture, which is the only surviving classical text on the subject.

Ancient Roman architects had a broader remit than our modern equivalents, being responsible for engineering, urban planning, materials, HVAC, acoustics, plumbing, and a whole host of other sub-specialties. De Architectura attempts to break down this massive field and describe it in simple, comprehensible terms.

Sandy has read to me from the books on materials and pavements and decorative plasterwork (which relate to her particular interest in Roman mosaics). Having done my share of construction and plastering, I’m pretty familiar with how we use those materials today. Other than adjustments for climate, it’s shocking how little has changed.

|

| An ancient Roman concrete vault in Rome, from the Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine, c. 312 AD. Can we possibly improve on concrete structures that lasted two millennia? |

We don’t seem to produce such brilliant generalists in the modern era. I wonder why that is? You can read De architectura here.

Let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in Maine in 2014 or Rochester at any time. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!