It’s not an emotional response or mere fault finding.

This week I begin a new online class dedicated to critique. Since it’s a totally new idea, the shape of this class is evolving. However, the plan is that students will bring work they’ve done on their own for analysis within the group. The hope is that we can develop a sort of executive function that will oversee our painting processes outside of class. This, as you can imagine, is much harder than “hold your brush like this” painting classes.

Critique is a long-standing tool in every intellectual discipline, artistic and technical. However, it’s more straightforward to tell your co-worker, “I can’t duplicate your results,” than it is to put into words why a painting isn’t working. “I don’t know about art, but I know what I like,” is only a funny joke because it’s to a large degree true.

What critique is not is an emotional response. It must be disciplined and systematic, but art is at the same time intuitive and subjective. We bridge that gap by analyzing works based on a series of values:

- Focal point

- Line

- Value

- Color

- Balance

- Shape and form

- Rhythm and movement

- Texture (brushwork)

These elements of design transcend style or period. Every painting includes them to some degree. The critic must consider how they work together. Do they coalesce into something arresting or not? If not, what forces are blocking the full expression of the artist’s idea?

There should be no censure involved. We’re all intelligent adults; if our ideas aren’t working, it’s because we’ve run into a problem that another set of eyes can help us unravel.

The very first question we must ask (and answer) is, what are you trying to do or say in this painting? That’s not always simple, so it deserves time. Every subsequent point of discussion should be weighted in regards to that answer. For example, if what interested me was the loneliness of a home on a rocky crag, my composition, color, brushwork all need to support that aloofness.

Criticism should never be mere fault-finding. There is a seed of brilliance in almost every painting, and it needs to be enlarged upon. That means discussing the merits of a painting as much as discussing its faults.

|

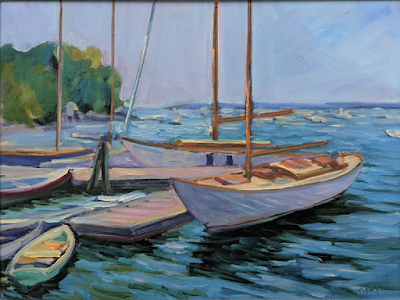

| Belfast Harbor, 11X14, available. |

For critique to work well, the critic and artist must both approach the process with humility and mutual respect. I once took a painting I couldn’t finish to a noted teacher for criticism. She told me that it looked like a ‘bad Chagall.’ In trying to execute her ideas on the canvas, I completely destroyed my own vision. My self-doubt met her self-confidence in a terrible concatenation.

I’m speaking here of narrow peer criticism. There’s a larger world of art criticism that seeks to analyze artists in terms of their culture and times, but it has nothing to do with us.

By the way, I’m also starting my mid-coast plein air sessions tomorrow. There’s more than ample room in this class, so if you’re interested, email me for more information.