We don’t know why prehistoric man created the 360 ft.-long prehistoric Uffington White Horse in Britain, but every generation is both amazed and moved by it. Conversely, miniatures dazzle us with their meticulous craftsmanship. In very large or very small works, we’re immediately transported out of the ordinary. That is why The Heart of the Andes by Frederic Edwin Church must be seen in person—the scope is lost in photos.

The scale of the figures within a painting can make its message more powerful. Here, four masters show us how it’s done.

Wanderer above the Sea of Fog is by the great German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich. He doesn’t spell out the identity of the model; in fact, the man is turned away from the viewer. He is an Everyman with whom we are meant to identify. He is centered in the canvas (saved from being static by the S-curve of his body) and is larger than the landscape itself. Friedrich wants us to focus on our human responses and not the landscape itself, as symbolic of uncertainty as it is.

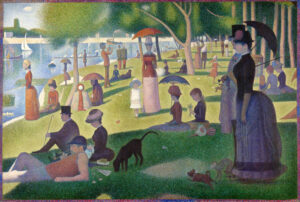

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Georges Seurat is one of the most famous paintings in art history. It’s the seminal work of Neo-Impressionism. It was birthed with some difficulty, as Seurat labored over it for three years. Observe the scale of the figures. They range from the monumental couple on the right with their weird little monkey to the distant figures in the background. Using figures of various sizes, Seurat deftly created depth without atmospherics or modeling. Compare this painting to its companion piece, Bathers at Asnières, which takes a more conventional approach to creating depth.

Many Hudson River School paintings are sermons on canvas, and Thomas Cole’s The Oxbow: View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm is no exception. You are meant to see the American landscape as an Arcadia where man and nature live in harmony. There’s also nascent American myth here, celebrating our story of discovery, exploration and settlement just as they began to fade into history. Cole hammers this home with the Hebrew lettering in the logging clearcut. It spells either “Noah” or “Shaddai” (the Almighty) depending on whether you’re reading it right-side-up or from the God’s-eye-view.

Cole painted himself into The Oxbow. He’s so tiny it will take you a moment to find him. Look in the ravine to the left of his kit and umbrella. By making himself so small he drives home the point that we are mere specks in Creation.

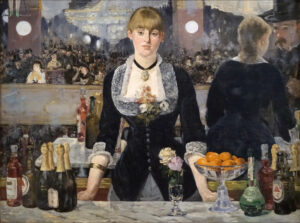

Much has been written about the ‘impossibility’ of the reflections in Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (at top). The gentleman at the far right is enigmatic; he’s both transactional and nightmarish. Note the feet of the trapeze artist at the far left and the Bass Pale Ale bottle, which hasn’t changed in 140 years.

The barmaid’s face is life-size, and she is assessing us straight-on. Whether we’re looking at exhaustion, sadness, or resignation is hard to say. By making her life-size, Manet hammers home the power of her straightforward gaze. This painting isn’t just a mirror in a bar; it’s a mirror on our own souls.

Manet was dying of syphilis when he painted this, suffering severe pain and paralysis. Controversy has raged about the identity and character of the model, known only as Suzon. That hardly matters, because what we see in her eyes is a reflection of Manet’s, and by extension, our, thoughts.

If you’ve ever thought about taking one of my workshops aboard schooner American Eagle, here’s a lovely account from writer Georgette Diamandi, who joined us this past September.