Tomorrow I start teaching a class on composition and brushwork. In preparation I’m building an exercise based on Edgar Payne‘s Composition of Outdoor Painting. Thinking about each example has brought me back to the works of two brilliant designers, Édouard Manet and Wayne Thiebaud.

I don’t like using the same artist for each example. Instead, I try to mix it up, to demonstrate to my students that fundamental compositions have been used throughout history. Thiebaud was a celebrated modernist, but you can find Payne’s armatures in every one of Thiebaud’s paintings. Despite his pop art color and subjects, he rested everything on classical design.

Edgar Payne wrote his book more than eighty years ago, and it’s still the best composition book I’ve read. You can see the images here, or you can learn to apply them in one of my painting classes or workshops.

Rookie error

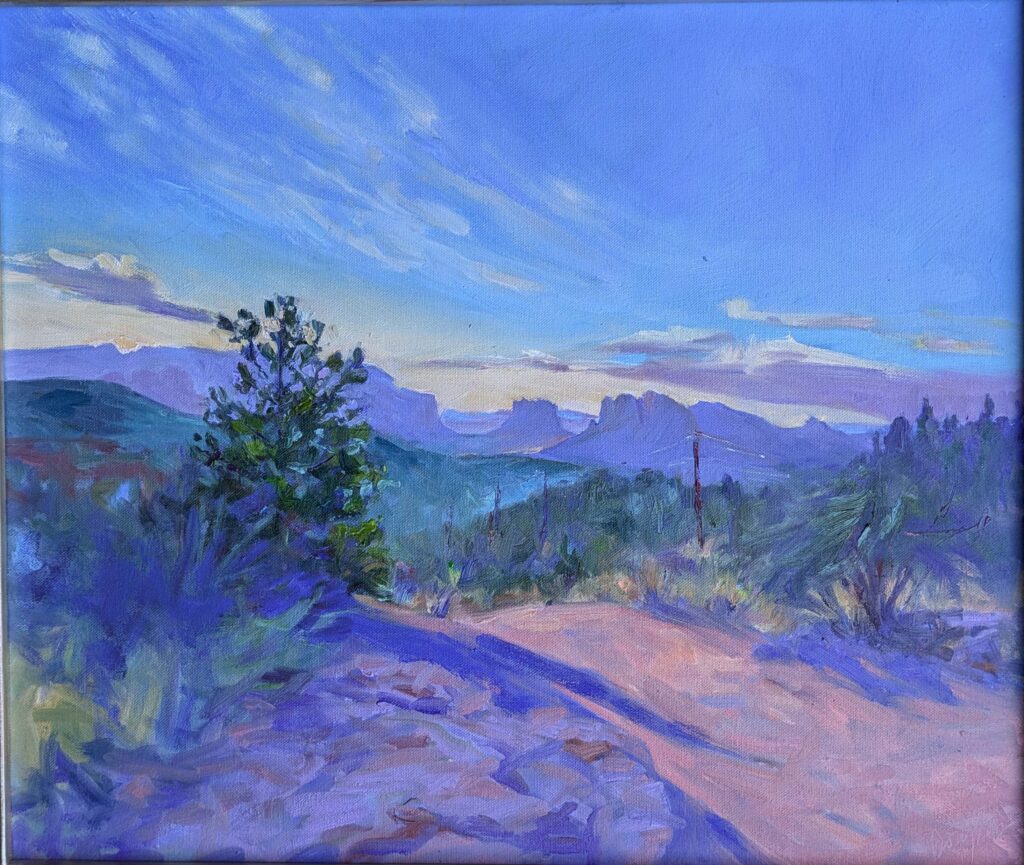

Beginning painters think those armatures are about placing objects. Instead, they are always about value (light or dark), although that value sometimes takes the form of an object. There are times when objects and shadows mingle; for example, a large piñon and some small creosote bushes can combine with their shadows to form a dark triangular mass. But it’s always the weight of the darks and lights that holds a painting together, not the nominal subject matter.

Paintings compel not because of detail but with value. It’s not enough, for example, that an object runs at a diagonal; you must make a persuasive shift along that diagonal. This is the primary lesson of Winslow Homer’s incredible seascapes.

Composition rests on the following principles:

- The human eye responds first to shifts in value, and following that, in shifts in chroma and hue;

- We follow hard edges and lines;

- We filter out passages of soft edges and low contrast, and indeed we need them as interludes of rest;

- We like divisions of space that aren’t easily solved or regular.

Let’s talk about our feelings

Just as Payne distilled the basic structures of paintings into simple shapes, he also recognized that artists can use certain structures to provoke feelings. For example, clashing shapes provoke anxiety, while unbroken horizontal lines are fundamentally calm.

Music, sculpture, poetry, painting, and every other fine art form relies on internal, formal structure to be intelligible. This is easiest to see in music, where the beginner starts by learning chords and patterns. These patterns are (in western music, anyway) universal, and they’re learned long before the student starts writing complex musical compositions.

Music is an abstract art because it’s all about tonal relationships, with very little realism needed to make us understand the theme. A composer doesn’t need little bird sounds to tell us he’s writing about spring. Likewise, the painter doesn’t need to festoon little birdies on his canvas to tell us he’s painting about spring. That should already be apparent in the light, structure and tone of his work.

The strength of the painting is laid down before the artist first applies paint, in the form of a structural idea-a sketch or series of sketches that work out a plan for the painting.

All good painting rests on good abstract design. Still, most realist painters don’t spend nearly enough time considering abstract design, even when they understand the critical importance of line and value. Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World doesn’t rely much on hue or chroma for its impact. It’s a washed-out pink, a lot of dull greens and golds, and a significant amount of grey. And yet it was the most successful figurative painting of the 20th century, because it sublimated everything to a simple armature—Payne’s ‘three-spot’.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.

We had an Edgar Payne boat painting in the gallery that I worked at in Vermont. I must’ve looked at it 100 times because it was all the things you described above, and simply beautiful at the same time. I never would have understood all the thought process that went into the work, until you it broke down. Thanks Carol!