“I want AI to do my laundry and dishes, so I can do art and writing, not for AI to do my art and writing so I can do laundry and dishes,” wrote Joanna Maciejewska, in what is probably the most apt comment of our times. I’m inundated with AI images. Their funny imperfections are offset by internal biases that are downright scary, especially when casual observers can’t tell them from reality.

Wabi-sabi art says that the maker is human

Wabi-sabi is a Japanese aesthetic that embraces the imperfect, impermanent and incomplete. It is trending right now in interior design and in the preciousness of Meghan Markle’s American Orchard Riviera, but there’s a legitimate heart call there. If you’ve ever attended a wedding in a barn or had a drink in a Mason jar, you’ve lived wabi-sabi art, American-style.

Wabi-sabi occupies the same position in the Japanese aesthetic as the Greek ideals of beauty and perfection have occupied in western art for more than 2000 years. It’s the perfect antidote to the increasingly slick imitation of reality that AI represents.

Most of us, if we think about wabi-sabi art at all, think of it in terms of kintsugi, or the art of repairing broken things that makes them better than they were when perfect. That’s cool, but it’s only one aspect of wabi-sabi. How can thinking about the imperfect, impermanent and incomplete improve our art?

Nothing lasts

I’ve written about how art is not eternal. If it’s not destroyed in a spasm of iconoclasm, it is left to rot or simply forgotten. The Greeks were arguably the greatest sculptors of the human form, and yet fewer than 30 substantially intact, large-scale bronze statues survive from classical and Hellenistic Greece. In fact, most of all artwork ever made no longer survives.

That’s a real bummer if you’re painting in the hope that your fame will outlive you, but that goal is a trap. It stops us from focusing on communicating with our fellow men in the here-and-now. “Yesterday’s the past, tomorrow’s the future, but today is a gift,” as they say.

Nothing is finished

“How do I tell if my painting is finished?” is one of the most common questions I’m asked.

Art history is replete with examples of paintings that never seemed to get done. Leonardo da Vinci picked away at his Mona Lisa for sixteen years; he only quit working on it when his hand became paralyzed. That is less painting than obsession.

‘Finished’ presumes that all the questions are answered. That sounds boring to me, but luckily I can’t say I’ve ever gotten there. I just get sick of working on things.

Nothing is perfect

The more technology gives us perfection, the more we embrace imperfection.

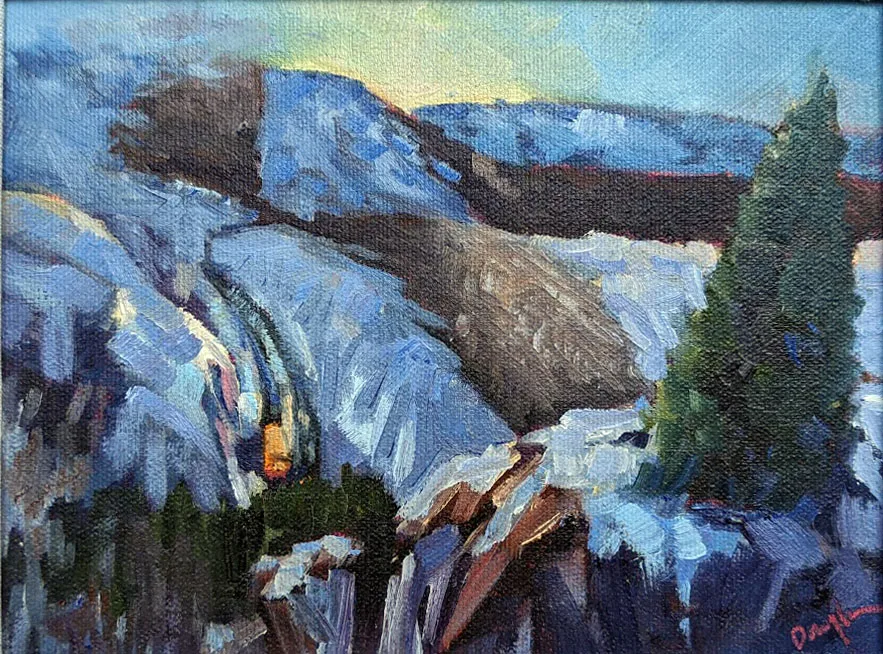

This is hardly my idea; it’s been the general thrust of painting since the advent of photography. Photography explains tangible reality faster and better than paintings do. What we do far better than AI and photography is reveal the hand (and therefore the psyche) of the maker.

Is this an excuse for half-hearted work?

Of course not! You still are being held to high standards; you’re just not required to be perfect. And as we all know, perfect is the enemy of good, which is why I’m ending this essay on a cliché.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.

All Flesh Is As Grass is , I think, my absolute favorite painting of yours.

Thank you!

Don’t forget “happy little accidents” 🙂