Drawing six similar objects will teach you to observe details.

|

| Reliant rigged as a sloop. |

I once got a commission to paint Lazy Jack II in Camden Harbor. I was pretty happy with the results. As I finished, two deckhands from another boat stopped to look at it. Their eyes met. “You’ve got the…” one started. “It’s not important,” said the other, and they quickly walked away. I’ve never figured out what’s wrong in that painting, but I did realize that you can only fudge the details so far. The experts will find you out.

In the normal course of things, you’re not going to see many square-rigged vessels here in mid-coast Maine (although you could see

USS Constitution if you drive down to Boston). You’ll see fore-and-aft rigs, where the sails run above the keel rather than perpendicular to it.

|

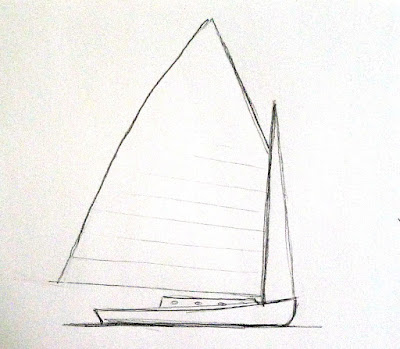

| A Bermuda-rigged sloop. This is the most common silhouette you’ll see wherever pleasure boats congregate. |

A boat’s sails all suspend from a vertical spar called the mast. This transmits all the power of the wind pushing the boat through the water. It’s really a marvel of engineering, especially since the kinks were worked out before the age of composite materials. There are some other spars whose names will be useful to know: booms, which run along the bottom of the sails, and gaffs, which get raised up in the air. Not every sailboat has gaffs, but they all have at least one mast and boom to hold the sails taut.

|

| A gaff-rigged catboat. |

A catboat is small and has a single sail on a single mast set well forward in the bow, or front of the boat. (I think this would be the perfect painter’s boat, especially if I could find one towable with my Prius.)

A sloop also has one mast, with only one sail in front of the mast. If that head-sail multiplies, your boat has morphed into a cutter.

Reliance, the 1903 America’s Cup defender, could be rigged as either a sloop or cutter. I drew

Reliance to illustrate that single-masted boats can be gaff-rigged as well as Bermuda-rigged. She was a peculiar thing, built only to win America’s Cup and then sold for scrap. Like all transitory things, she was, oh, so pretty.

|

| A ketch. Angelique is far prettier. |

Ketches and yawls have two masts, with the back (mizzen) sail smaller than the front sail. The difference is that in a ketch (like

Angelique) the aft mast is meant to push. It’s pretty big. A yawl’s mizzen sail is very wee, almost vestigial, and is way to the back of the boat. It’s basically an air rudder, used to keep things in balance.

|

| A yawl (or y’all, for those of you from the south). |

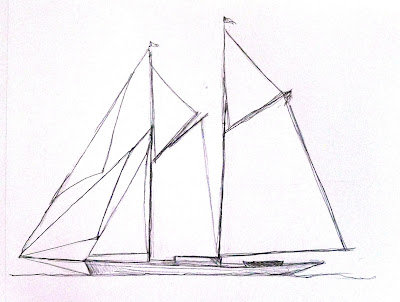

Schooners started out having two masts, but three-masted schooners were introduced around 1800, and the spars proliferated from there. The only seven-masted schooner, the steel-hulled

Thomas W. Lawson, was built in 1902. It was 395 ft. long.

While you might run across

Victory Chimes, a three-masted schooner out of Rockland, the rest of the Maine windjammer fleet have two masts. A schooner’s forward mast is shorter than its mainmast, giving it an appearance of eagerness. Schooners come in all kinds of sail configurations.

|

| A schooner’s foremast is shorter than its mainmast. |

Your assignment is to find a photo of each of these sailing vessels and sketch them out as I did, paying particular attention to where the sails attach to the masts, the angles at which the gaffs are running, and the height of the masts in relationship to the length of the hull. This is not about sailing, it’s about attention to the details that matter.

If you aren’t interested in boats, you can do the same exercise with cars, motorcycles, or varieties of apples; I don’t care what they are, just that you have six objects from the same class of objects.

The point of this exercise is not to create six beautiful boat drawings. It is to show you how much you learn by sketching. At the end of it, you should have a clear sense of why sketching in the field is a far better preparation for painting than taking photos is.

Remember, those of you who love boats: we’ll be sailing with

Captain John Foss on the most beautiful of all windjammers—

American Eagle—in June, studying watercolor painting on the move. For more information, see

here.

|

| My little assistants. I drew the boats and they colored. |