|

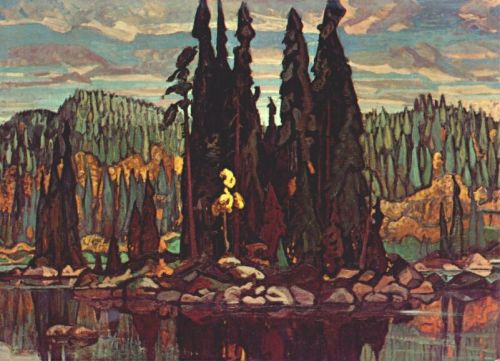

| American Landscape with Indian Camp, by Ralph Blakelock, showing the damage that can result from tinkering with technique. |

Yesterday I mentioned the deterioration in Albert Pinkham Ryder’s paintings. He was not, by any means, the only painter whose work has suffered over time.

Prior to the 19th century, painters had a limited range of materials at their disposal: vegetable oils, waxes, plant gums and resins, and eggs, milk, and animal hides. Pigments were made by either grinding minerals or extracting dyes from plants and insects. Some of the extracted pigments turned out to be fugitive (meaning they aren’t light-fast) but generally those old paintings are in remarkably good condition.

The 19th and 20th centuries were a period of constant modification of materials. Some changes have been inarguably for the better—for example, there would have been no Impressionism had there not been an explosion of new pigments in the mid-19th century.

|

| Holy Virgin Mary by Chris Ofili. Now, seriously, how does a conservator preserve elephant dung stuck to a canvas? (And in this case, does it really even matter?) |

Whenever I visit the modern collection at the

Albright-Knox Art Gallery I am struck anew by how badly some of their paintings have aged. 20th century artists had no reason not to use the tremendous variety of synthetic materials that industry was creating—synthetic media, plastics, adhesives, and drying agents. As the definition of what constituted painting broke down, artists also incorporated materials the ancients would have understood to be ephemeral or beneath their calling: dung, straw, paper, urine, blood, etc.

|

| Woman, by Willem de Kooning, 1965. He definitely experimented with obscure additives to keep his paints open longer, but so far scientists haven’t actually found any mayonnaise in his paintings. |

Willem de Kooning, for example, allegedly mixed house paint, safflower oil, water, oil and egg in with his paints. Some surfaces of his paintings remain soft and sticky fifty years later, which has to present a bit of a problem for conservators. Anselm Kiefer has used lead, sand and straw in many of his paintings.

|

| Mildew attacking orange paint in a Clyfford Still painting. |

Learning to paint in the 1960s and 1970s, I used a medium made of equal parts varnish, turpentine and linseed oil, with a few drops of cobalt drier thrown in. Having seen the ghastly cracking of fifty-year-old paintings made with this medium, I decided that medium shouldn’t be a DIY project. Better to trust the scientists who work for the reputable paint manufacturers.

Another technique I discontinued is underpainting my oil paintings in acrylics. Certainly, oil-over-acrylic won’t delaminate the way acrylic-over-oil will, but who can say how the two paint systems will interact over time? I think it’s fine to paint in oils on acrylic-primed canvas, but any part of the painting that shows through (and that includes the toning) should be done in oils.

It was trendy a few decades ago to dismiss the archival aspects of painting, to embrace the ephemeral. If, say, de Kooning is the equal of Rembrandt, why would we not want to see his works survive for the ages?

One more workshop left this year, and it starts a week from today! Join me or let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in 2014. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!