Two things I learned teaching my workshop last week.

|

| Kamillah Ramos at the Grand Canyon. |

I start each class and workshop by handing my students protocols for painting in oils and watercolor. “If you follow these steps,” I tell them, “you will understand how to paint.” These instructions are not unique; they’re how most successful artists work through drawing, composition, and paint application.

Just try it for the length of the class, I tell them. If it doesn’t improve your painting, go back to what you were doing before. But I’m confident that following this traditional approach works. Anyways, most people take painting classes because they recognize that something in their system isn’t working.

A set of step-by-steps is oddly liberating. Working out the problems in advance leads to looser and more lyrical brushwork.

Student Becca Wilson responded by telling me that there’s a phrase for this: “creativity loves constraints.” Bam.

The idea that limits can lead to extraordinary creative output seems counterintuitive. After all, the creative pursuits (and particularly the visual arts) are often thought to be about feelings and thus limit- and rule-free. In reality, they’re quite the opposite. Every creative pursuit has its own established practice, and painting is no exception.

Constraints set up processes within which problems can be solved. Separating painting into discrete steps—value study, color mixing and then, finally, brushwork—helps cut it down into manageable pieces. Only when you can do the steps automatically will you find your authentic, unique artistic voice.

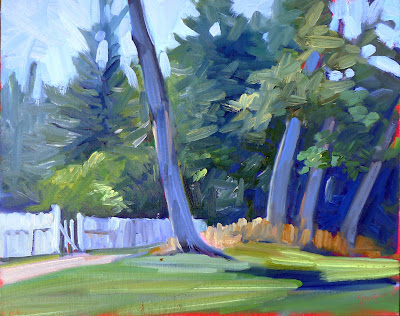

Kamillah Ramos and I were painting on Mather Point at 5:30 AM yesterday morning. This is a busy time at the Grand Canyon. The weather is good and schools are on spring break. Hundreds of people came by in the 4.5 hours we were painting, and many of them stopped to ask us questions or comment on our work.

“There’s nothing like plein air painting for changing the vibe of a place,” Kamillah said. She’s so right.

Our workshop painted in six separate locations in Sedona, which was also jam-packed with tourists. People might have found our presence irritating, but instead they were interested and enthusiastic. In fact, in decades of painting outside, I’ve had universally-positive reactions from passers-by.

Artists are very much a cultural and economic asset, and that’s worth remembering.

(Sorry this is brief but I’m about to board a red-eye to Portland.)