|

| We call this Paleolithic relief The Venus of Laussel but we really have no idea what it is. Perhaps it’s the world’s first self-portrait by an artist. |

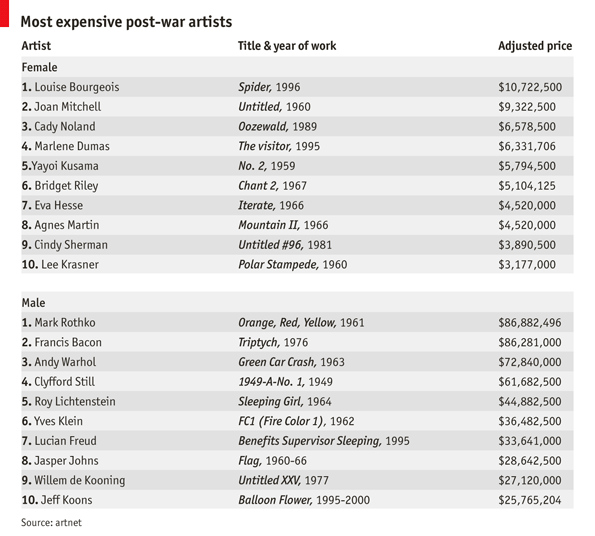

In the art world, it’s no big secret that there’s a high price to be paid for being a woman. The chart below was assembled before the recent $142.4 million sale price for Francis Bacon’s “Three Studies of Lucian Freud,” but the reality remains the same. Masterworks by female painters are consistently devalued in the marketplace.

Having participated in roughly a billion art shows, I can assure you that even if it’s getting better, it’s still very much a man’s world out there. On every level, paintings by male artists earn more money than those by female artists.

I came of age during the Modernist era, which associated creativity with virility. It was not, in fact, until I was much older that I began to learn about great women artists like Artemisia Gentileschi, Rosa Bonheur, or Käthe Kollwitz. This shows you how pervasive was the myth that art is a man’s province. In fact, I would say that the question of whether women could even make good art was still an open one in the 1960s and 1970s.

A recent survey of Paleolithic stenciled handprints by Professor Dean Snow from Pennsylvania State University certainly undermines that view. After sampling a number of European caves containing Paleolithic artwork, he estimates that about 75 percent of the handprint art in them was done by women.

|

| Handprints at El Castillo in Spain, among the world’s oldest art. |

In human populations, there is general sexual dimorphism of hands—the most reliable part being that the ratio of the length of the second digit (index finger) to the length of the fourth digit (ring finger) is greater in women than in men. However, even this isn’t foolproof; in modern European populations, it is only true about 60% of the time.

“I thought the fact that we had so much overlap in the modern world would make it impossible to determine the sex of the ancient handprints. But, old hands all fall at or beyond the extremes of the modern populations. Sexual dimorphism was greater then than it is now,” said Professor Snow.

That in itself raises a fascinating question: what in modern life suppresses gender dimorphism? Is it our abandonment of traditional gender roles? That in turn comes back to the question of what, in fact, are our traditional gender roles?

.jpg/594px-Paintings_from_the_Chauvet_cave_(museum_replica).jpg) |

| A museum replica of cave paintings at Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in southern France. |

Paleolithic cave art has been presumed by modern social scientists to be talismanic, bringing good hunting to its creators. Of course, hunting is a traditionally male activity in a hunter-gatherer society, which means it must have been made by men. But is it true that men were the predominant hunters in Paleolithic society? And was primitive man as singlemindedly religious as we’d like to believe, or is it possible that the cave artists were decorating those spaces for the sheer joy of it?

Analysis of the cave art really tells us more about our own biases than anything.

Let me know if you’re interested in painting with me in Maine in 2014 or Rochester at any time. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops!

.jpg/594px-Paintings_from_the_Chauvet_cave_(museum_replica).jpg)