The human brain has an unfortunate tendency to skip over the parts of a plan it doesn’t like.

|

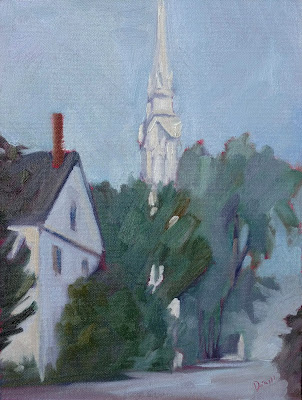

| Desert long view, 9X12, oil on canvasboard, $696 unframed. |

I never expected to be flying back from my workshop in Sedona with four wet canvases, so I only brought a two-canvas PanelPak. Whoops, bad planning—but it was based on prior experience. I seldom have time for anything but a basic demo when teaching workshops.

“Do you want me to mail those?” Ed Buonvecchio, my monitor, asked me. No, I could jury-rig something using waxed-paper and an elastic band. I’ve done it many times before, but this time, something slid. My dawn painting of the Grand Canyon smeared. Whoops, I should have accepted help when it was offered.

|

| Camel Head, 9X12, oil on canvasboard, $696 unframed. |

Oh, well. That gave me the opportunity to demonstrate glazing to my Monday night Zoom class, but I think the painting is irreparably damaged. It will have to be completely repainted, and at that point it’s no longer plein air, meaning I’m no longer interested.

That happened after I dropped both Grand Canyon paintings jelly-side down on the sidewalk. Whoops, I should have made two trips to the car.

That’s not usually a deadly problem, as I tend to paint leaner in the field than in the studio. Thin paint sticks to the canvas better than its juicy cousin. The twigs and leaf litter will brush out when the paintings are fully dry.

|

| South Rim of the Grand Canyon, 9X12, oil on canvasboard, $696 unframed. |

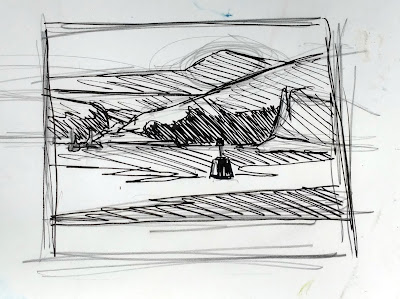

“Do you always do a value sketch first?” Ed asked me—with a small dash of skepticism—during the workshop.

“Only when I want my painting to come out well,” I replied.

The human brain has an unfortunate tendency to skip over the parts of a plan it doesn’t like, and the less articulated the plan, the more opportunities for bad assumptions. The consequences have come to be known as Murphy’s Law: anything that can go wrong, will.

We see that law of unintended consequences in every endeavor, not just painting. Looking back on mistakes, we can almost always identify where we went wrong. “If only I’d…” is our universal response. Advance planning can’t eliminate all disasters, but it sure cuts down on them.

|

| Painting, super-briefly, at the Grand Canyon. |

Planning means different things to different painters. To many (including me) it’s a simple, rough value sketch or notanoutlining the basic composition. To others, like Andrew Wyeth, it means a complex series of sketches working out all the problem areas in a painting.

But there is no planning hack in art that allows you to skim over the critical composition questions.

“I don’t want to spend all my time doing a sketch!” one student complained. It’s a common misconception that a painting moves faster and is more visceral if we don’t spend time on the value sketch and grisaille. But a painting without a plan takes longer to finish, is more tentative, and often is just a hopeful approximation of what we first envisioned.

But at dawn at the Grand Canyon, I ignored my own oft-stated instructions. Like everyone else, I have excuses: I was exhausted, it was still pitch-black, and the light would change fast. The result was a sub-optimal composition. So, I’m not really that heartbroken that the painting was ruined by my bad packing. It was the only one of the four that I was ambivalent about.