My dog always knows when I’m getting ready to leave. He attaches himself to me, following me from place to place as I go through my workday. I don’t think I’m dropping non-verbal clues. I think he’s listening to my conversations and understands far more than we think dogs are capable of.

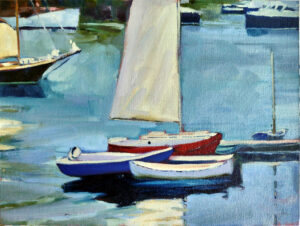

I’m heading down to Rockport, Massachusetts today for Cape Ann Plein Air. This is a premier plein air event; a number of people I haven’t seen since the start of the pandemic will be there.

When I get home, I have a week to get organized and then it’s off to Sedona Plein Air. There, I know only Ed Buonvecchio and juror John Caggiano. He’ll also be at Cape Ann as a painter this week. That’s not as weird as it sounds. There’s really nobody better to judge plein air painting than a fellow plein air artist.

Then it’s home in time to set up my schedule for 2023. I have four firm dates on my calendar so far:

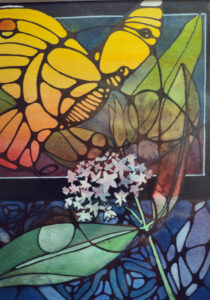

- Toward Amazing Color, Sedona, AZ—March 20-24, 2023. Sedona is a stunningly beautiful place that’s steeped in art history. What better place to learn about color than among the towering red sandstone bluffs, the muted greens of the chaparral, and that big, blue sky? An added plus for northerners—Sedona is warm in March!

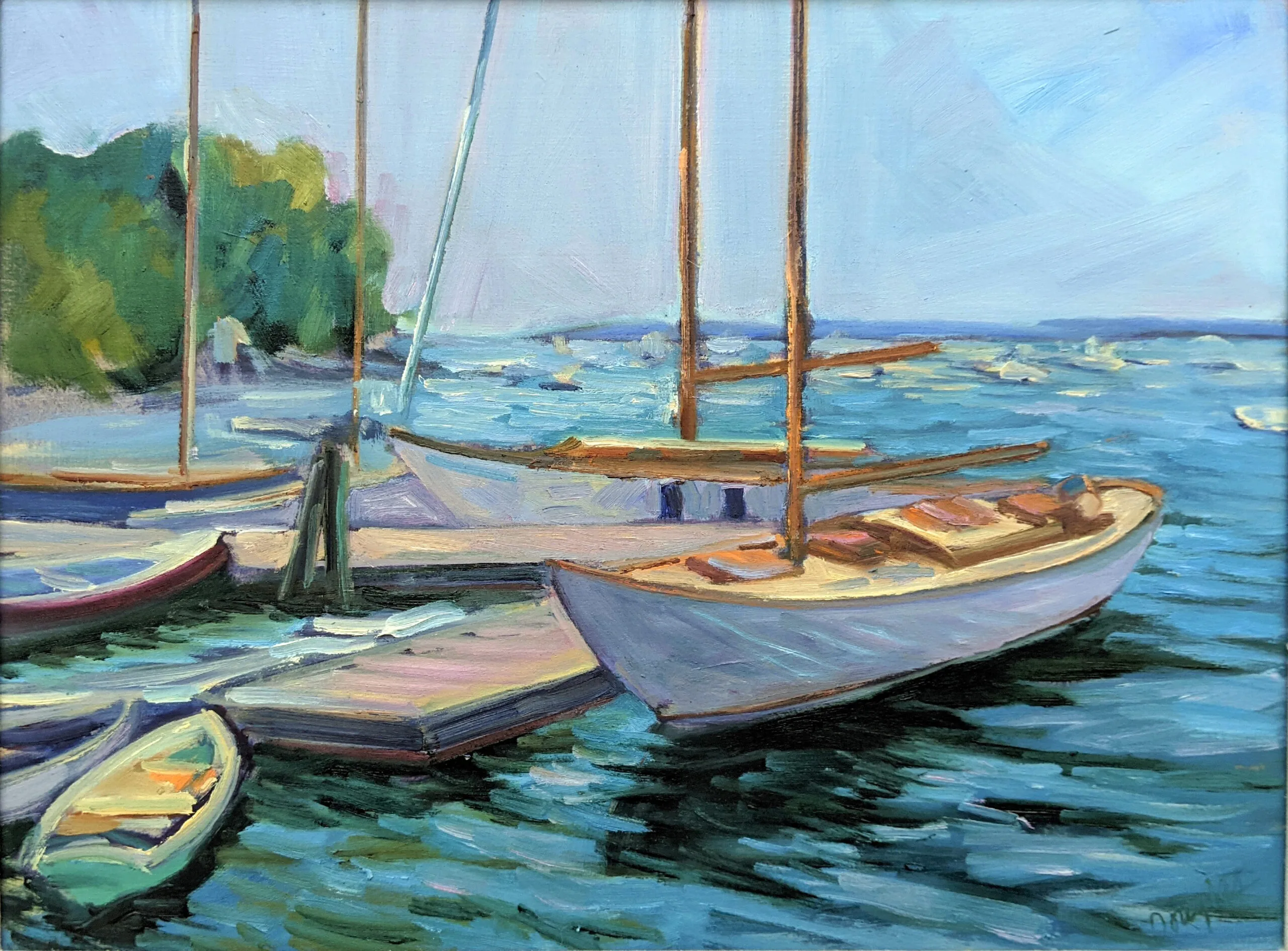

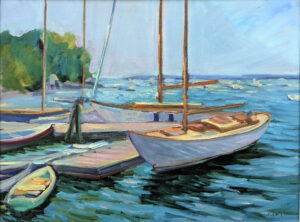

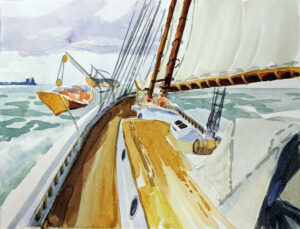

- Watercolor workshop aboard schooner American Eagle—June 20-24, 2023. This is the summer solstice, which gives us the longest possible period in which to paint. All professional-quality materials are included, and we welcome painters at all levels. In addition to wonderful sailing on an historic vessel, there are beautiful village walks and calm rows around quiet harbors.

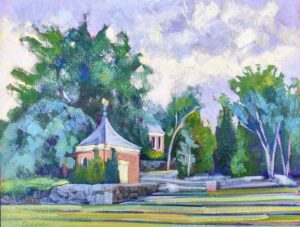

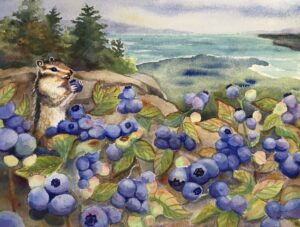

- Sea & Sky at Schoodic—August 6-11, 2023. This is in Acadia National Park, one of the nation’s true beauty spots. Since accommodations are available at the Institute, it saves you the trouble of looking for a hotel in an area that’s truly back of beyond.

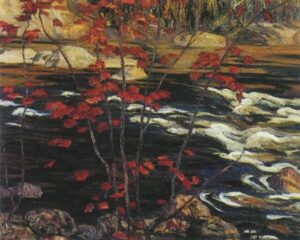

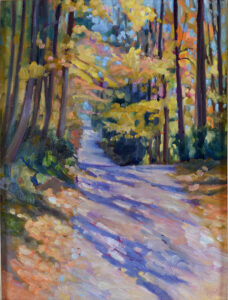

- Watercolor workshop aboard schooner American Eagle—September 16-20, 2023. Again, all materials are included, and we welcome painters at all levels. This is my favorite time to sail, as the water’s warm and the skies are magnificent. Changing foliage glows against the dark evergreen trees and the deep blues of the bay.

These workshops aren’t up on my website yet, although you can register for Sedona directly. I’ve been a one-woman shop and I’m very busy in the summer. This fall, however, I’m doing things a little differently. My daughter Laura Boucher has been helping me with IT, video, and other online material. Of course, she can only publish what I give her, and I’m just learning about this stuff.

If you’ve eyeballed these workshops in prior years, now’s the time to pencil in the dates and email me to make sure you get the updated information as soon as it’s published. My workshops regularly sell out.

My gallery has closed for the season. Paintings don’t benefit from the wide temperature swings we see in October, so they’re bundled up cozily in their storage unit.

Our timing was perfect—on Sunday we took down the tent and on Monday four cords of firewood were dropped in the adjacent lawn. Somehow, I need to make the time to stack it.

This autumn would have been even more chaotic had surgery not forced me to slow down earlier this month. My favorite meme recently is “Adulthood is saying ‘But after this week things will slow down,’ over and over until you die.” At times, it sure feels that way.