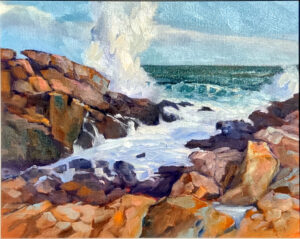

When I was in Cape Ann last week, I broke my brush washing tank. (It retaliated by dousing me with filthy mineral spirits.) Eric Jacobsen took me to a neat little art store in Beverly called Art Supplies Wholesale. Alas, they don’t sell metal tanks. “No matter,” I said, and asked Rae O’Shea for a jam jar. I can replace the tank this week at home.

I live in an area with a great assortment of art stores nearby. There’s Rockport Blueprint in Camden, Fiddlehead in Belfast, Salt Bay in Damariscotta, and Artist & Craftsman in Portland. If you live where there are art stores, for heaven’s sake patronize them. There may come a time when you need something fast, and you’ll be grateful for that shop around the corner. And the price spread between online shopping and your local store is not as large as you think.

Some of us don’t have that luxury. I got this letter from a painter in Kansas:

“My oils are in dire shape and I would like to order new paint. I would like your advice on where I should order art supplies. My town is a shopping desert, there is only a Walmart here. Basically, we are at the mercy of ordering everything online.

“I drove to a Michaels in another town this past weekend and looked at what they had, but it was very limited. What are some good online resources to restock my oils?”

Those big-box craft stores sometimes surprise me; for example, I needed acrylic paint and brushes in another small town and the big-box craft store carried Golden. That’s my preferred brand. But in general, what craft stores carry in stock (vs. what’s on their website) is insufficient for serious painting. Worse, you have to navigate aisles of silk flowers, stamps and beads to get to it.

Art supplies are a fairly large industry in the US, with $819.0m in sales expected this year. As a category, it’s in decline, whereas its cousin, arts and craft supplies, is growing. That tells you where most people shop.

There are three major art suppliers online: Dick Blick, Jerry’s Artarama, and Cheap Joe’s. All three concentrate on offering an enormous array of options at the lowest possible prices. That makes them great for the person who knows what they’re looking for, but can be a trap for the uninitiated. That’s one reason that teachers should write and maintain a good supply list.

Dakota Art Pastels specializes in only one line of products-pastels, pastel papers and pastel pencils. Their approach is very different; they share information about pastel hardness and allow you to buy samplers of different brands before you commit to a pricey set. Theirs is one of the few websites I boot around on just for fun.

Then there are specialist stores like Rochester Art Supply, which would be my go-to for encaustics. These stores combine a strong local presence and a good internet sales base.

Paradoxically, if you just need one item and have Amazon Prime, it can be your cheapest solution. Again, you need to know exactly what you’re looking for, as they often sell deceptive knock-offs. See my post about how Google drives viewers toward flawed Meeden pochade boxes.

There are some products you must buy directly from the vendors. I use RGH paints, made by Rolf Haerem and his assistant in a little shop in Colonie, NY. Panel Pak wet painting carriers and most pochade boxes are items that come directly from vendors. Some online vendors carry limited supplies of fine products-Raymar art boards and Rosemary and Co. brushes are two examples. However, the full lines can only be accessed directly from the manufacturers themselves.