I grew up with the 11th Edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, which is why I’m conversant with the careers of Gladstone and Disraeli (they fought a lot) and not so hot on quantum mechanics. As fun as it was to follow rabbit trails across the Encyclopædia‘s 28,150 pages, Wikipedia is faster and easier, and better-indexed, too.

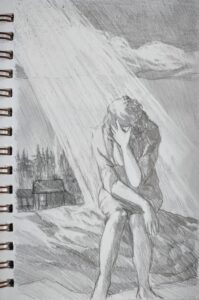

That’s how I came across the cadaver monument, which is a type of effigy tomb featuring a decomposing body. In the best of these, the deceased is freshly laid out on a bier and we can ‘see’ his decomposing corpse beneath. Death was a significant part of life right up to modern times, but the cadaver monument was characteristic of the late Middle Ages, when the Black Death kept sic transit gloria mundi on everyone’s lips.

These monuments are a form of memento mori, meant to remind us that life is transient and all earthly striving is vanity. Of course, the people with cadaver monuments were those whom earthly striving had rewarded well, including Richard Fleming, Bishop of Lincoln, whose tomb reads:

“Stand, seeing in me, who is eaten by worms, what you will be. I, who was once young and beautiful to look on… lie under thick clods. Worldly pomp, honour, recognition, what heights there are, what they, pray, if not dreams, folly? …All things are put to flight by cruel death, like shadows…”

Pray your loved ones out of Purgatory

By the late Middle Ages, Purgatory had become an established part of Catholic theology. Praying for the dead was practical, as it could effectively reduce their time and suffering in purgation. Cadaver monuments reminded the living to pray for the dead, along with powerfully suggesting that they knock off their own sinning.

The en-vie (in life) figure, on top, was a status symbol. He was dressed in his swishest best. It’s the en-transi (in transit) effigy in conjunction with the en-vie figure that makes the cadaver tomb so powerful – that and the sculptors’ obvious familiarity with death and decomposition.

Isolated en-transi sculptures are more typical, although none of them are common – there are only 44 extant cadaver monuments of any kind in Britain. The British examples are more restrained than their continental counterparts, which sometimes include the vermin that speed corpses into decomposition. Perhaps the greatest of these is the Cadaver Tomb of René of Chalon, by Ligier Richier. Legend says that the putrefied figure originally clutched René of Chalon‘s actual withered heart in its raised right hand.

Alice de la Pole, the grand-daughter of Geoffrey Chaucer, is the only British woman with a cadaver monument. Wealthy and powerful in her own right, she chose to be shown as an emaciated old lady. Her eyes are half-open, the better to see the saints above.

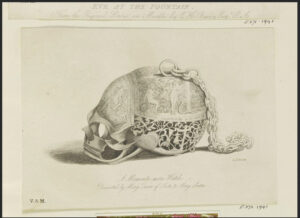

Death’s Head watches

Then there’s the phenomenon of the Death’s Head pocket watch, which continues to this day, albeit in a stylized form. These are memento mori lite, as they reached their vogue in the 17th and 18th centuries, the so-called Age of Reason. The cases were engraved with images of Adam and Eve, Death with his sickle, and other morbid themes. The watch was viewed by opening the skull’s jaw.

It’s rumored that Mary, Queen of Scots had one. That’s a possibility, since pocket watches were an innovation of the 16th century. According to legend, it was given to her favorite lady-in-waiting upon Mary’s execution. If it ever really existed, it’s long vanished.

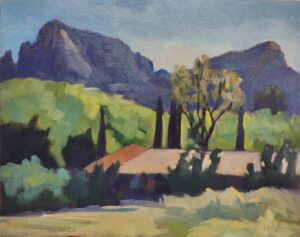

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

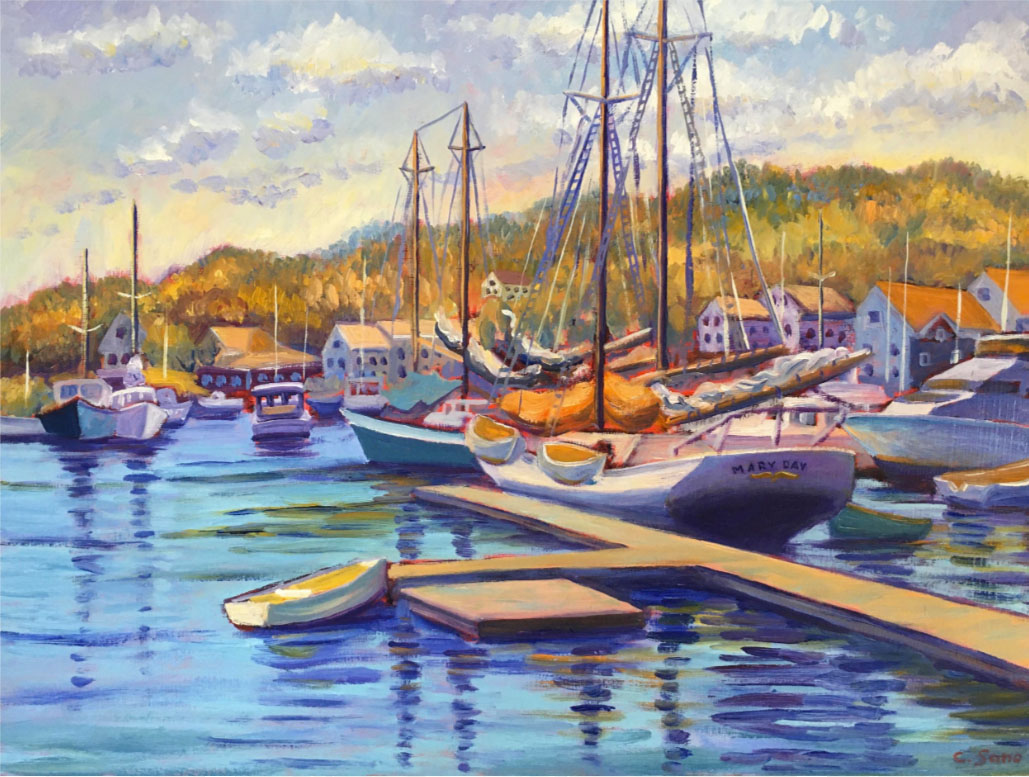

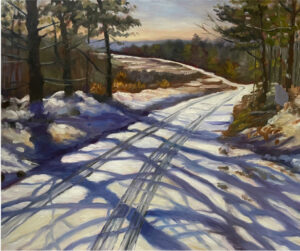

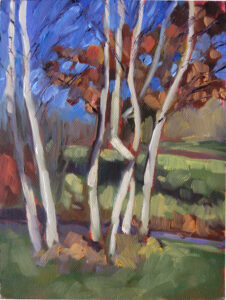

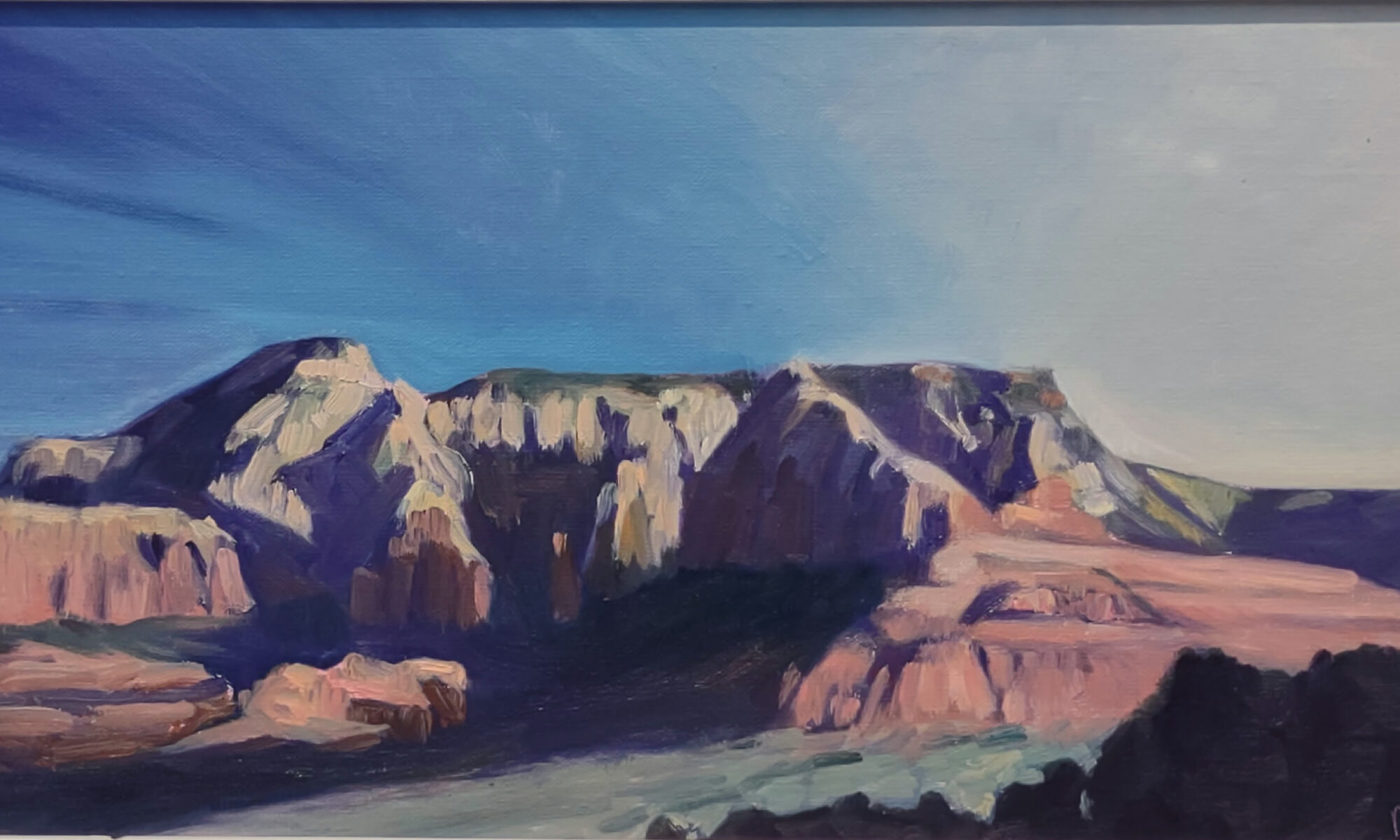

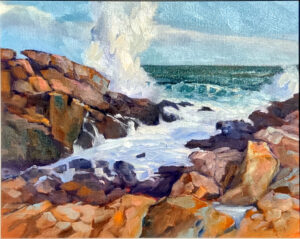

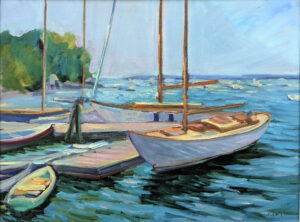

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

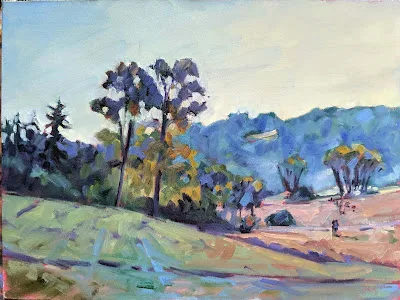

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

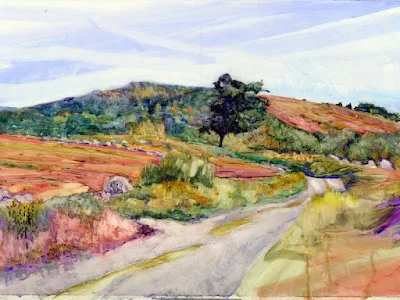

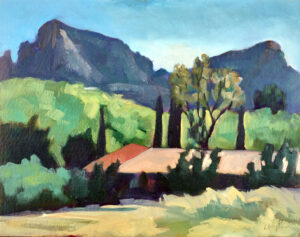

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

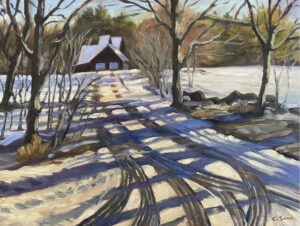

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.