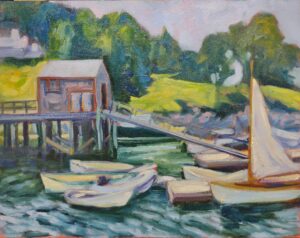

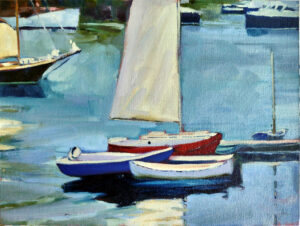

We all ‘know’ not to plunk our subject square in the middle of our composition, don’t we? Last week I mentioned the great outdoorswoman Sandra Hildreth, and in return, she sent me this photo of something she’d painted recently. It’s a great example of the power of selective symmetry and of Carol’s first rule of composition: Don’t Be Boring.

In addition to being the driving force behind the Adirondack Plein Air Festival, Sandy taught high school art for 34 years. She knows her way around a paintbrush and a pochade box.

First, let her describe how symmetry shouldn’t be done: “The artist might put her mountain right in the middle of the composition, and it ends up shaped like a simple triangle. The forest on either side is the same shape and color, and then there is a foreground of solid green.” That’s indeed how it often goes down. It’s a recipe for static boredom.

Sandy consciously chose to put her mountain square in the middle of her picture, “but then I focused on everything that was not symmetrical. I looked for every shape and color change, and made sure nothing on the left and right matched. I’m not suggesting I painted a masterpiece, but I painted a simple view and made it visually interesting.”

There’s power in the tension between the dominant massif and the forest and clouds that wouldn’t have been there had she chosen the obvious solution, which would be to move the massif to one side.

“The other possibility is what my high school students usually did: choose the simplest composition possible.” By that she means centering everything. “That’s easy to draw, but boring.”

“How do you teach people to open their minds to diversity and asymmetry rather than make everything smooth and equal?” she asked me.

One of the first things people say about artists is that we “see things differently,” usually as a preface to the hoary old canard, “it must be nice to be born with talent.”

I can’t speak for Sandy, but I was lucky enough to have parents who encouraged my drawing, and a father who knew how to draw and taught me. I’m pretty sure that most successful artists start off with conventional aesthetics. Then they grind that middling viewpoint away through hundreds of hours of drawing. All that observation trains them to observe closely, to see the minute differences that elevate a real mountain above a boring old triangle.

That’s why I’m such a fanatic about making my students draw, draw, and draw some more-and then reflect on those drawings. I know it’s unfashionable to tell people they cannot paint without drawing chops, but it’s an unfortunate truth. I’m not talking about the ability to copy a photo, but the ability to see an object in three dimensions and reduce it to two on paper. Good artists see planes and shapes and that is what gives a painting dimension. How do you learn that? Practice, my friend, is worth more than the best drawing teacher in the world. But if you’re completely baffled, you can start with this book.

Plein air painters, in particular, sometimes make a fetish of working fast with little preparation. It shows in the results. All the bravura brushwork in the world can’t hold up a poor composition.

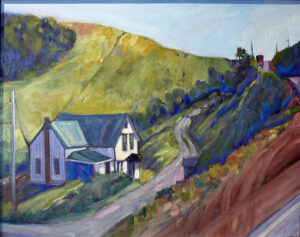

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.