“My friend is paralyzed at the thought of painting something that does not turn out good,” a reader wrote. “I keep telling her that experimenting is liberating and the goal is not to end up with a masterpiece every time.”

Everyone experiences performance anxiety occasionally. It may be prompted by demoing, by being in a competitive event, or even just when we encounter a tricky passage in a painting. “I’ve experienced it a few times when I am far into the painting and it looks good but it’s not finished yet,” my correspondent added. “This leads to a ‘don’t mess it up now’ attitude that affects the result.

“How can I help my friend get past this?”

Process, not results

Focusing on the results instead of the process is a great way to rob yourself of the joy of creativity. Many years ago, I had a student who announced at the beginning of each class who she planned to give her painting to. She was setting herself up for failure, week after week. Her painting would get all bound up in her fear of disappointing someone she loved. It’s no surprise that she didn’t stick with it.

We call concentrating on process being ‘in the zone.’ It’s a transcendent feeling, and worth striving for.

Desensitization

The more you do something, the less anxious you’ll be. I used to be terrified of public speaking, so much so that I needed beta blockers to do any kind of presentation. Years of teaching have burned that out of me. Today I can comfortably speak to large groups. Through repeated, escalating exposure, I desensitized myself to my trigger.

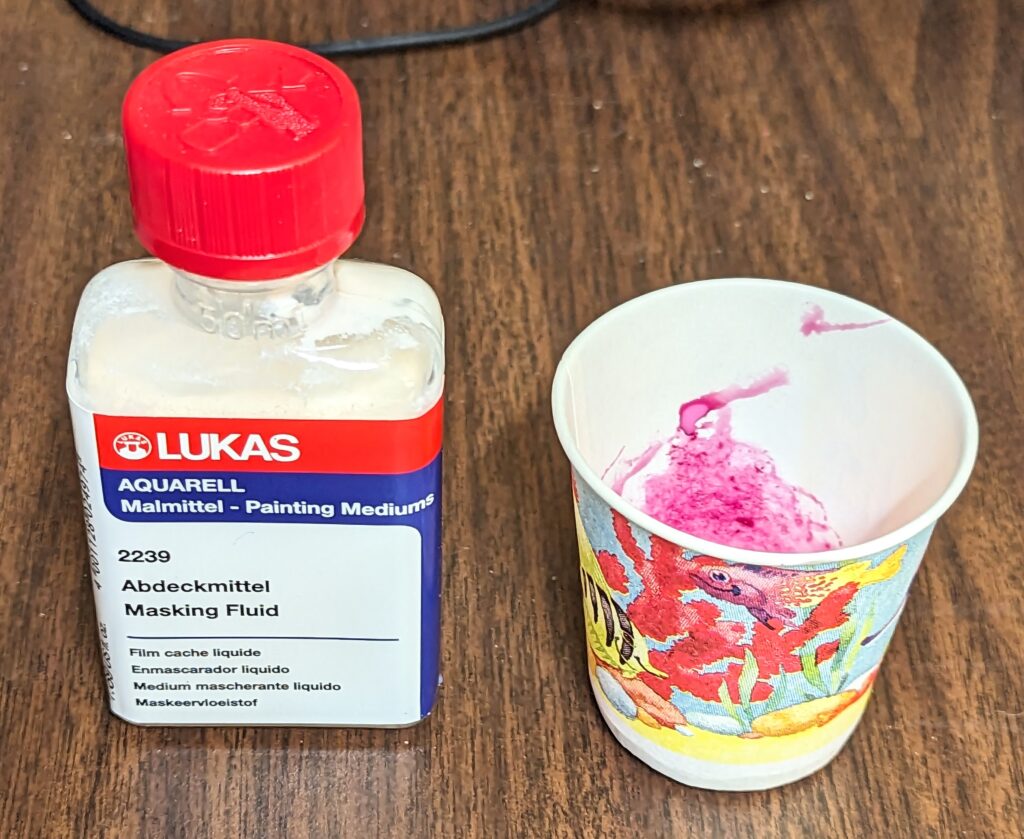

Desensitization is a powerful tool in Cognitive Behavior Therapy, so we know it works. How can we apply it to painting? By starting with the small steps – drawing, color mixing, and thumbnail paintings – we can slowly build our confidence for more expansive works. That’s yet another good reason to draw every day.

Of course, it helps to ask what is the root of your fear. Is it lack of knowledge? That’s fixable. Perfectionism? It helps to realize that there’s nothing perfect in art; in fact, that’s its charm.

Are you telling yourself that you can’t rise to the occasion? I do this when I clean my house. “It’s too much; I’ll never finish this!” I say, and then I’m mad. If I can shut off those negative thoughts and just concentrate on the work itself, I have a fine time scrubbing.

One of the best ways to reduce anxiety is to be prepared. Whether that means learning to draw or mastering the steps of painting, the more confident you feel, the less anxious you’ll be.

Is it anxiety or excitement?

Both make your heart race and give you butterflies in your stomach. A little nervousness can be helpful; it can elevate your performance. The difference is that when you’re anxious, you worry about everything that can go wrong, instead of seeing the potential for success. Instead of trying to calm yourself down (which never works anyways) try to channel that energy into excitement.

How do you rate your overall well-being?

I’m a proponent of physical exercise. We all know it releases endorphins (whatever they are), but it also calms us down. People frequently comment about my dog’s perfect deportment; he is well-behaved because he does many trail miles with me every morning. As a bonus, I’ve survived two cancers and have no blood pressure, blood sugar, or cholesterol problems at the grand old age of 64.

Seek Support

If you are still unsure and troubled, take a class or workshop. The best of them are supportive communities that will help you master technique and feel great about doing art.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

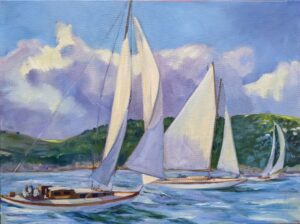

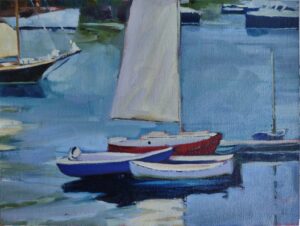

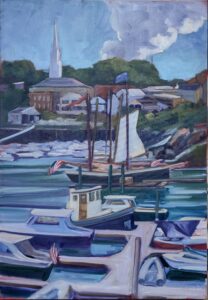

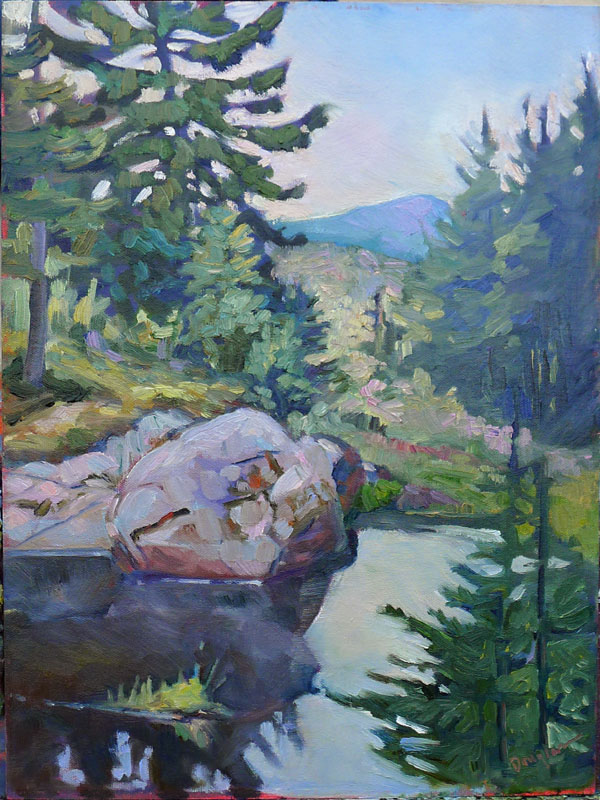

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.