Recently, someone called me ‘formulaic.’ I laughed because all experienced painters have systems; some just let beginners flail around because it cuts down on the competition. Systematic painting is no different from my carpenter friend Dave knowing how to get professional results with minimal struggle. Professionals know where it pays to bear down, and where bearing down is useless.

Systematic painting gets the mechanics out of the way and makes room for true creativity to emerge. It also helps when time and pressure threaten to derail you.

You can overcome your nerves

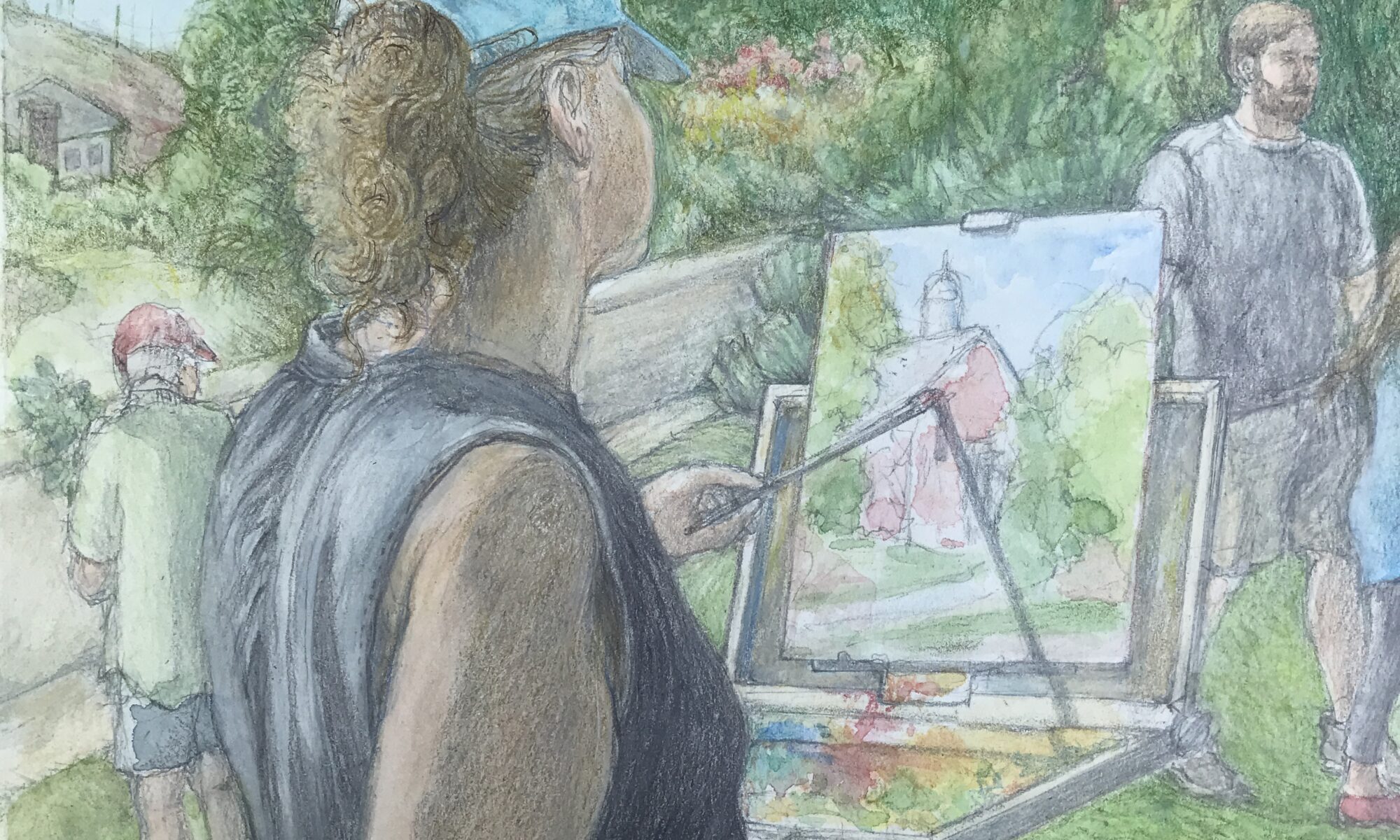

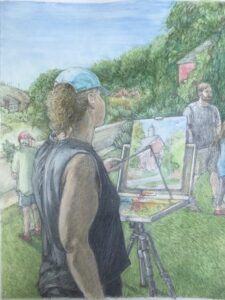

I was a mess at my very first plein air event. I started using opaque colors way too soon, with too much mineral spirits. Daisy de Puthod, bless her, lectured me. “Carol, what are you doing? You know better than that!” It snapped me out of my momentary insanity.

I have several decades of systematic painting under my belt since then. Although I still get nervy at times, I no longer panic. When I’m stressed, I just fall back on what I know, a simple system that always works.

You can work in a tight time window

In 2018, I traveled to Edinburgh, Scotland, to do a portrait. This was no open-ended affair where I could putz around and deliver when I felt like it. I had exactly eight days from conception to completion, including a trip to Greyfriars Art Shop to get supplies.

That wouldn’t have worked had I not stuck to my protocol. I had it planned almost to the hour, and there were no snafus. In fact, I had enough time left to go see the delightfully weird Rosslyn Chapel.

You can overcome your emotions

There are paintings with an emotional wallop that can threaten to derail you. I’m working on one right now (with a short hiatus to go teach a few workshops). It’s a picture of my grandmother and her cronies in her South Buffalo backyard, and includes me as a toddler on a swing. I have no good reference materials, and I’m frequently finding myself thwacked upside the head by memories, not all of them pleasant. But I can continue because I’m working to a system.

It helps when you have the attention span of a rabbit

This week the turnscrew on my pochade box decided to strip itself. Painting is no fun when your box keeps falling down, but I stand it back up and get on with it. I’m the poster child for ADHD, so it’s only system that keeps me on track in situations like these.

Why do I mention this?

I’ve spent the last seven months doing steps 1-4 of a systematic painting instruction system called Seven Protocols for Successful Oil Painters. This is what I’d intended to write as a ‘how to paint’ book but realized that an interactive instructional system comprised of lectures, exercises, and quizzes would teach far more thoroughly.

By the time you read this, my beta testers will be done and The Essential Grisaille will be live. That means four segments are finished:

The Perfect Palette-what paints should you buy and why?

The Value Drawing-where you work out the thorny questions of light and dark.

The Correct Composition-the ‘secret sauce’ that makes some paintings transcendent.

The Essential Grisaille–moving that composition onto the canvas without losing what makes it great.

As I told a reader recently, if you start at the beginning and faithfully do the exercises, you’ll probably be ready for the next section about the time I finish it. I intend to have this done by the end of the year, and I do believe it’s the most important work I’ve ever done.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

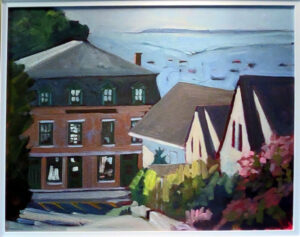

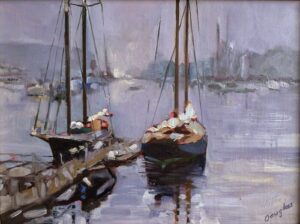

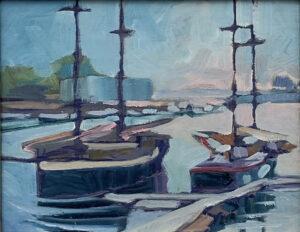

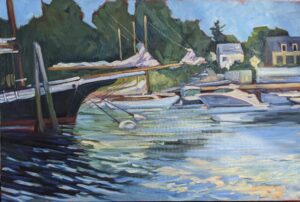

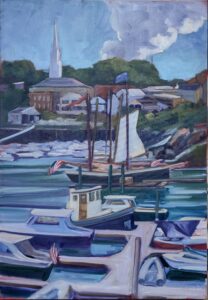

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

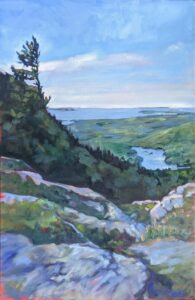

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.