I’m a driven person, but every once in a while, I’ll get myself into a situation where I’ve pushed the accelerator too hard for too long. The chassis is shaking, there’s black smoke streaming from the exhaust and I’m gunning for a breakdown. It’s time for me to stop.

The artists who study with me also tend to be driven. I’ll occasionally see that same fracturing in one of them. Exhaustion threatens to derail their progress. That’s especially true when things aren’t going well with their work. It’s very easy to be bleak when you’re overtired, and easy to be tired when you’re bummed out.

We’ve all heard that prolonged stress can contribute to a weakened immune system, digestive problems, headaches, weight gain or loss, trouble sleeping, heart disease, susceptibility to cancer, high blood pressure, and stroke. Unremitting chronic stress is tied to diminished cognitive function, so it can hinder our long-term productivity.

Stress is a delicate balance.

Too much stress, and you break down. Too little, and you get nowhere.

We have all met ‘artists’ who go to openings and talk about the work they might do; in fact, there sometimes seems to be an inverse relationship between how much people chatter about their work and how much they actually do.

But there are other very serious artists who have a different problem. “I have the time to paint, and I want to paint,” they tell me, “But I just don’t seem to do it.” They engage in avoidance techniques, like cleaning, that stop them from ever getting started. That’s anxiety.

I finally have the luxury to be able to treat art as a 9-5 job, but before that I tried very hard to make a schedule and stick with it. Going into the studio every day at the same time encourages your mind to get down to it and not squirm around looking for an escape hatch.

“I know you’re all terrified,” a painting teacher once told my class. She wasn’t entirely right, but self-doubt can be bubbling along just under the surface, even in people who seem extremely confident. And it can blindside you when you aren’t looking.

Creativity may look easy, but artists invest incredible effort to create that impression. Art, if done right, is both mentally and physically difficult. It doesn’t get easier over time. “Painting is easy when you don’t know how, but very difficult when you do,” said Edgar Degas.

Finding a balance that works

Sustainability is about finding a balance that allows you to prosper over the long term. Unlike Hercules, we can’t enlist Hermes and Athena to assist us in our labors, so we need to find ways to regroup. (By 165 AD, Hercules’ fellow Romans were celebrating 135 festival and other holidays a year. Medieval peasants had even more days off. Our ancestors could teach us a thing or two about rest.)

Most modern people don’t observe a Sabbath, more’s the pity. It’s a gift, not an obligation.

Worrying won’t make it better

I really hope that most of the time you’re painting you’re ‘in the zone,’ happily making artwork. But it isn’t always like that; as I mentioned above, making art is often anxiety-inducing.

Getting older helps if for no other reason than that we’re just too blasted tired to keep worrying. But whatever your age, try to check your anxieties, perfectionism, and other mental hiccups at the door of your studio. You’ll find you have a lot more energy to work.

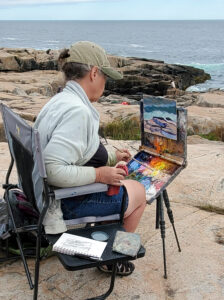

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.