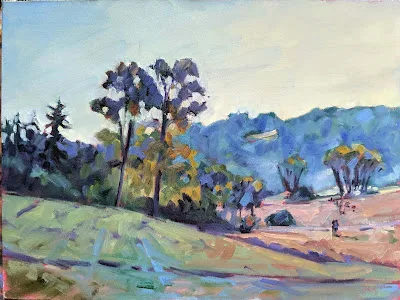

I had an extremely tight schedule this week. I leave for Sedona Plein Air at noon today, and I needed to finish recording video for Seven Protocols for Successful Oil Painters. I’m a person with one-day, one-week, one-year, and five-year plans, and I’m running behind.

I’m also a list-maker. When my schedule is overloaded, I just drop my gaze and focus on the next task. How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.

That’s where I was on Monday morning when we received a phone call that suddenly changed everything. (It’s not my news to share, but we and our family are fine, and that’s what matters.) My carefully-calibrated projections have been knocked sideways.

I needed to start a whole-life pivot while discharging my immediate responsibilities, all the while coping with that horrible buzzing in the head that accompanies extreme stress. By the grace of God, I did it, but it wasn’t easy.

By Tuesday, I was a little more sanguine. “This is not the first time I’ve been blindsided,” I told my husband. The accidental deaths of two of my siblings as teenagers and my two cancer diagnoses were much worse shocks.

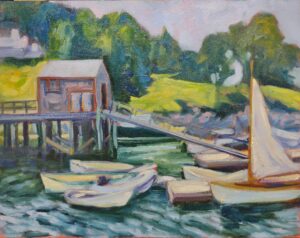

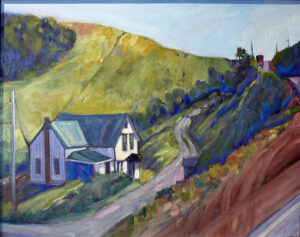

Being blindsided is different from run-of-the-mill bad news. When artist Kevin Beers lost thirteen paintings in the devastating Port Clyde fire on September 28, he had no warning of the disaster that was about to crash down. One minute, he was larking along, and the next, his body of work was gutted.

Being blindsided has an instant physiological effect. Your flight-or-fight response kicks in, adrenaline pumps and your mind races. At that moment, it’s hard to take any action, let alone sensible action.

There are silver linings to most clouds, although they sometimes take years to realize. I often muse about writing a book called “100 Best Things About Having Cancer.” Since it didn’t kill me, my first cancer was liberating. I stopped doing things I didn’t want to do. I finally did something about the psychic damage caused by my sister’s and brother’s deaths. You could say that cancer allowed me to finally be happy.

The day I learned I was having twins was a good shock. However, it had its moments. My husband was in grad school so I was the primary wage-earner. I spent three months on bed rest and was hospitalized for five weeks. I did lots of worrying, and none of my fears came true. We waste a lot of time worrying in this life.

Perhaps it’s true that challenge helps us develop resilience; I don’t know. My personal philosophy is that God has never let me down yet, and he won’t start now. Of course I have my moments just like everyone else; I frequently echo Doubting Thomas in prayer: “Lord, suspend my disbelief!”

Last Sunday, we had a visiting preacher named Gary Bolton. His vision is absurdly large, to plant new churches across Ireland (thereby neatly sidestepping the Protestant-Catholic divide). It would be so easy for him to lose heart and falter, but he’s applying the same logic I mentioned at the beginning of this post: How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.