First among the many things for which I’m thankful are you, the people who read my blog and are part of my community. This blog started almost two decades ago as a very clunky essay on WordPress, with almost no readers and rather stilted writing. That was back when my website was called Painter of Blight as a cruel mockery of Thomas Kinkade. We should not speak ill of the dead, and, anyway, I outgrew sophomoric humor. I think.

From there I migrated to Blogger, then to the Bangor Daily News, then back to Blogger and finally home to my own website. I’ve never totally understood the mechanics of moving a blog, which is why only the last move really worked, and why you’ll occasionally come across an old post where the pictures have disappeared.

Some years I barely wrote at all; others I wrote five days a week. Today this blog goes out to thousands of readers three times a week. It has a very high open rate by industry standards, and that’s down to you. Thank you.

It’s also reposted on social media, where, paradoxically, most people make their comments. (Hint: if you post them here, they last forever. However, you usually must wait for me to approve them. Any website that raises its head above the parapet is prone to denial of service attacks. Then there are the goofballs who think they can plug unrelated websites in the comments. That’s why our security is so high.)

A blog is a partnership between writer and reader. It wouldn’t happen without the input, questions, and ideas that you readers send me. Amazingly, I’ve never been stumped for an idea; right before the well runs dry, one of you always contacts me about something and-bam-there’s another post.

I used to write these ideas down in a tiny 35¢ notebook I referred to as my iPod touch. Amazingly, a tiny notebook can still be had for 35¢, but now I store our bright ideas in my computer.

I have a few obsessions besides painting. They are general history, art history, and the gender pay gap in the arts. You’ve traveled down many rabbit holes with me, from this potted history of the art model to the story of Vincent Van Gogh’s sister-in-law.

Today I talked to someone who asked me if I really planned on working until 80. “Yes,” I told him, “If my health holds out.” Some days I’m tired, some days I’m discouraged, but overall I have a tremendous amount of fun doing this gig. Thank you so much.

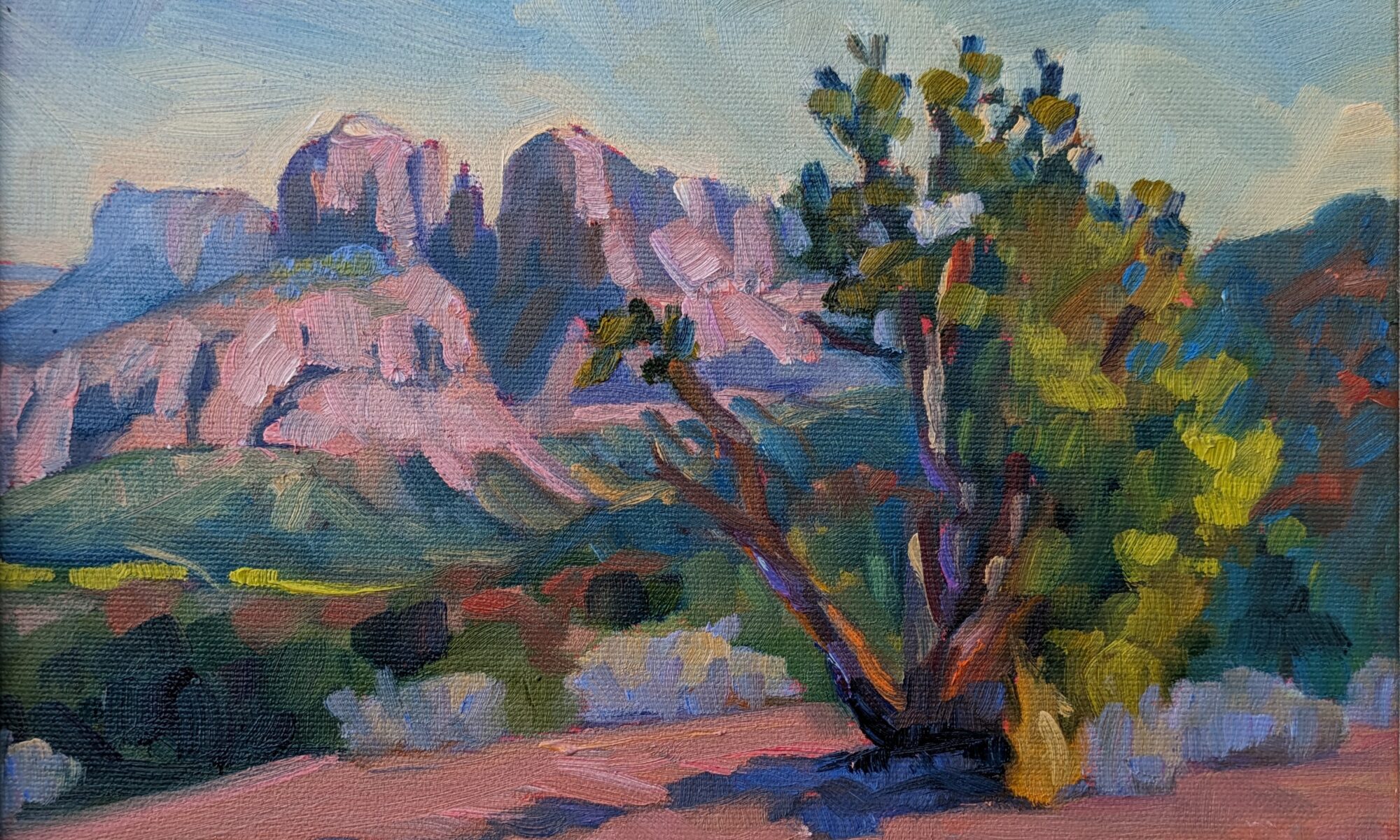

If you get my newsletters, you know that I’m offering a discount for all workshops for 2024. In appreciation for all my readers, I’m extending that to anyone who reads my blog anywhere. Just use the code EARLYBIRD at checkout to save $25 on your registration fee (except Sedona; but it’s still a great deal). This offer is good until the end of the year.

Save the date

I’m planning an online party on Friday, December 1, at 6 PM. More details soon, but you won’t want to miss it.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

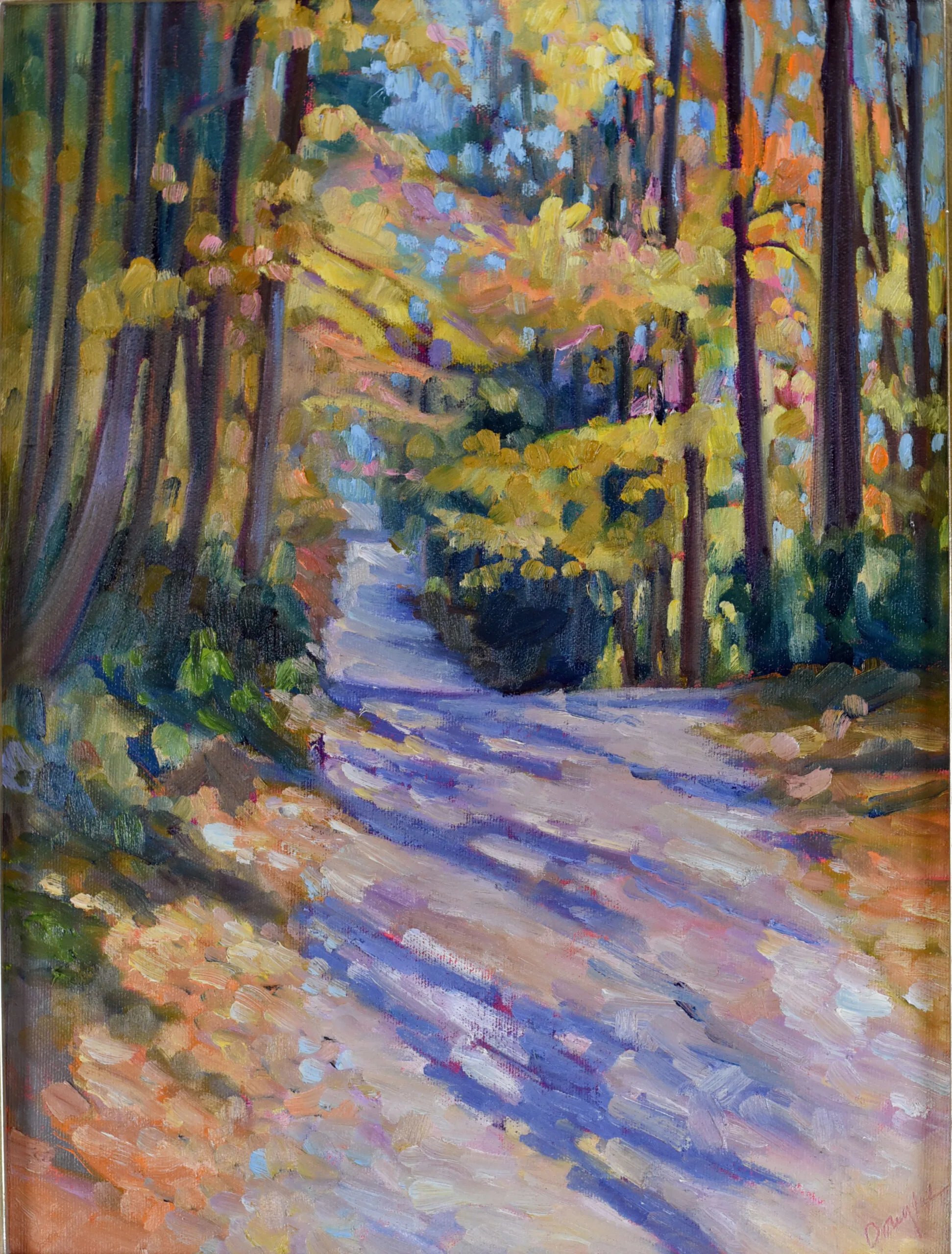

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.