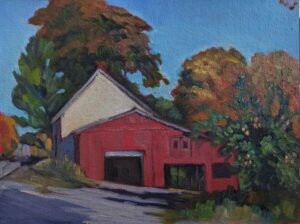

I’ve spent a lot of time this year working on projects without roadmaps. Such is the case with today’s Virtual First Friday. Not only have I never done one of these, I’ve never attended one. (You can preview the paintings here.)

My daughter Mary (the soapmaker) is riding shotgun for this. That’s a funny coincidence, since she is the kid who crossed Alaska and Canada with me. We didn’t follow a map then, either. She and her younger brother love geology; when she was feeling well, she spouted Rock Facts on the dating app Tinder, to the frustration of many young Canadian men. They didn’t understand that to some of us, geology is sexy.

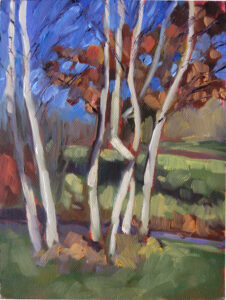

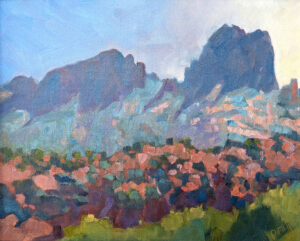

Mary tells me that the American Cordillera is that chain of mountain ranges that forms the ‘backbone’ of the Americas (and also the volcanic arc that’s our half of the Pacific Ring of Fire). It runs from Alaska’s Brooks Range, through Central America, along the Andes, and all the way to the very tip of Antarctica.

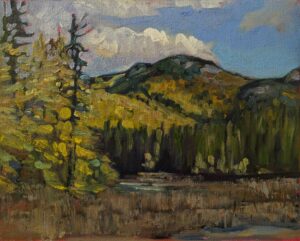

I’ve painted at both ends, in Alaska and Canada, and in Patagonia. While preparing for North to Southwest: A Plein Air Perspective, we considered the relationship between those trips. In one way, they were both defined by illness. Mary spiked a fever as we reached the Arctic Circle. It was mononucleosis, and she didn’t start to recover until we were in Quebec.

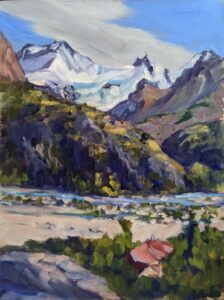

Our trip to Patagonia started the day of the world’s lockdown for COVID. Instead of hiking and painting in Argentina’s Parque Nacional Los Glaciares before heading out to Ushuaia, we were penned into smaller and smaller places, until we ended up in a hotel with an armed soldier at the door. Somehow, we all managed to get giardiasis. I don’t recommend it.

At six to ten million years old, the Andes are just babies; the mountains of Alaska and Northern Canada predate them by fifty million years, but both ranges are wild and fantastic.

Los Glaciares is located within the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, and I was able to paint the edges of several glaciers from the hostel grounds before we were sent to our rooms. On our trip across Canada, we brushed past the Kluane/Wrangell-St. Elias/Glacier Bay/Tatshenshini-Alsek Ice Field (that’s a mouthful) and stopped to visit the Columbia Ice Field, where I failed to paint the Athabasca Glacier. Conditions were just too miserable, so I did it later, in my studio.

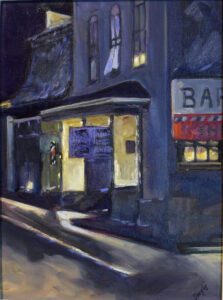

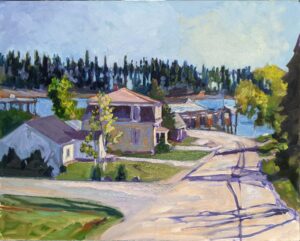

Mary and I have had a great time reminiscing about our drive. Despite our fantastic adventures, it’s the people who stand out: Heidie and Jerry Godfrey, who let us couch surf in Eagle River, AK; Gabriel-from-Quebec on Tinder, who told us about the feudal Île d’Orléans; Gordon Kish, the last resident of a Saskatchewan ghost town; and Kyle-from-Newfoundland, who told us the best place to get fish and chips in St. John’s.

Then there were Cristina and Guillermo, the innkeepers at Hosteria el Pilar outside of El Chaltén. When it was clear that they would be stuck with us, they extended their season and stayed with us in the Andes, where it was starting to snow. They had to scrape together meals for us and get us enough gasoline to make a break to Río Gallegos. And Jane Chapin. When the airline’s computer system crashed and threatened to strand us, she stood in the gate, not moving, until Doug and I were ticketed. Have I mentioned that I don’t speak any Spanish?

Mary and I are already scheming about another Great Adventure. Hopefully we’ll encounter new geology, new friends and no new illnesses. It’s not too late to attend tonight’s virtual opening of North to Southwest: A Plein Air Perspective. And if you’re interested in a Great Adventure of your own where you’ll meet awesome people and do beautiful paintings, registration is currently open for my 2024 workshops. (Use the code EARLYBIRD to get $25 off any workshop except Sedona.)

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

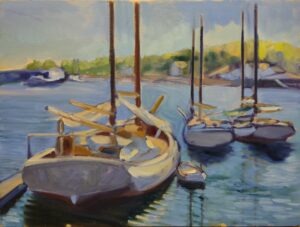

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.