“What’s the difference between sketching and drawing?” a student asked me. Since we were drinking cappuccino and watching a spectacular sunrise together, I asked my friend and fellow artist Jane Chapin.

“Sketching is a thumbnail, while drawing is more careful and measured,” she said. “In sketching you’re trying to work things out in your mind; in drawing, you already have your idea.”

Both sketching and drawing use the same essential tools: pencil, charcoal, ink, and pastel. However, these materials can be deployed in an almost infinite variety of ways.

The terms sketching and drawing are often used interchangeably, but they have slightly different meanings. These depend on the work’s purpose, level of finishing, and technique. There’s no hard line separating one from the other; that is subjective. Neither one is inherently better or more valuable than the other.

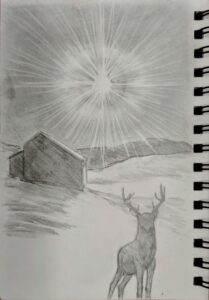

For me, sketches are quick, rough, informal representations of something I want to capture on the fly. Or, they’re experiments in design and composition before I commit myself to painting. Sometimes I use sketches to explain ideas. I’ve even sketched out ideas of things I want to build. (That’s almost always a mistake; I’d make far fewer errors if I drew plans with a ruler.)

Then there are the stupid cartoons I sometimes make for my grandkids. But whatever their purpose, sketches are immediate and without extraneous detail. They’re loose and imprecise.

In painting practice, sketches capture basic shapes and values without focusing on fine details. The term value drawing is really a misnomer; most of the time what we really mean is a value sketch. That’s especially true when we’re making thumbnails.

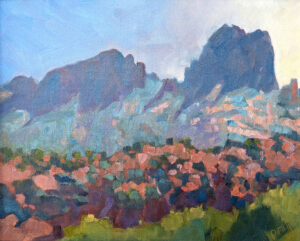

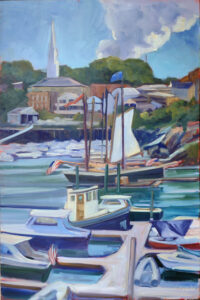

Then there is the field sketch, which is the painting equivalent of a pencil sketch. It is invariably on the small side. It can be used to record color notes or light effects, but it’s as different from a highly-finished painting as a pencil sketch is from a highly-detailed drawing.

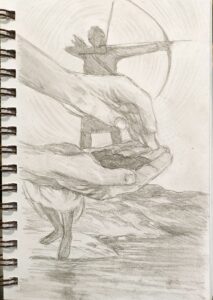

Drawings involve more careful measurement with thought-out perspective and proportion. They are usually more detailed, with a greater emphasis on accurate representation. Drawings can include subtle modeling, refined linework and intricacy. They can be highly complex. However, sometimes they’re starkly simplified; detail is deleted in favor of abstraction. The drawings of Vasily Kandinsky are just one example.

Sketches are generally done with quick strokes, using pencils, charcoal, or ink. No great emphasis is placed on sophistication or finish; instead, a sketch is all about spontaneity and intuition. Drawings, in contrast, are more cerebral, as is the case with mechanical and architectural renderings. Drawings are more likely to be made as final works of art, and are often done with better materials.

Of course, sometimes sketches evolve into drawings, as happens to me when I draw in church. I start with a germ of an idea, often nothing more than the intersection of two or three lines. As my subconscious mind drives my pencil, my conscious mind begins to see threads and connections. I erase, redraw, erase some more, and in less than an hour I have a finished drawing. It helps that my sketchbook is highly-erasable Bristol; I have endless opportunities for revision.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.