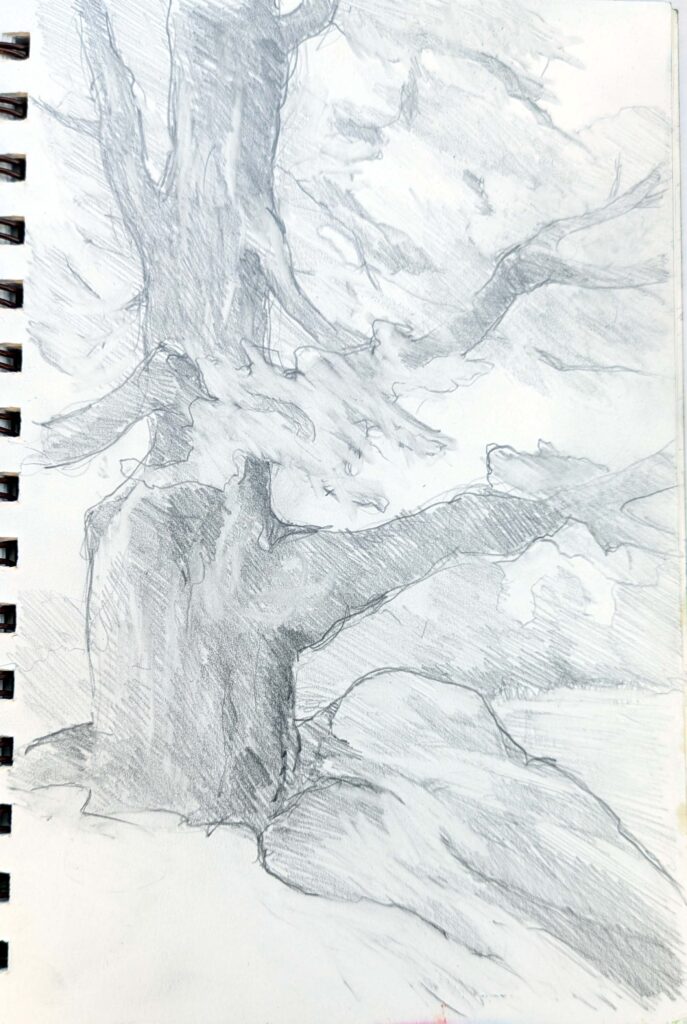

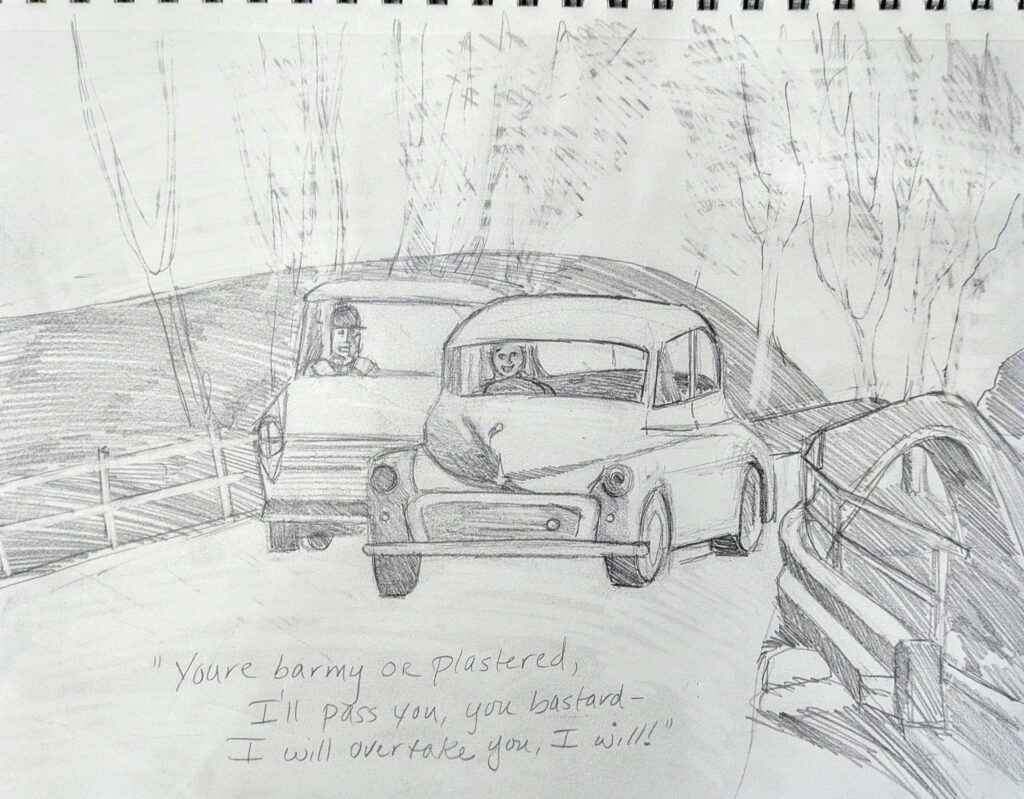

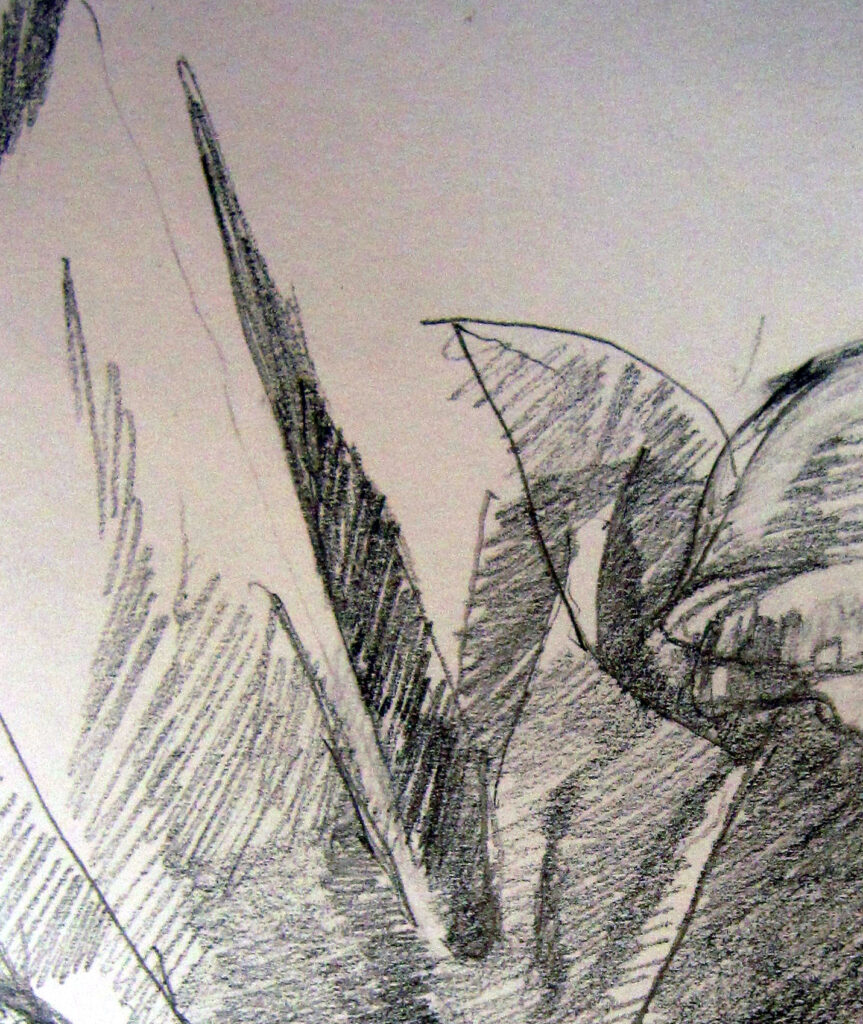

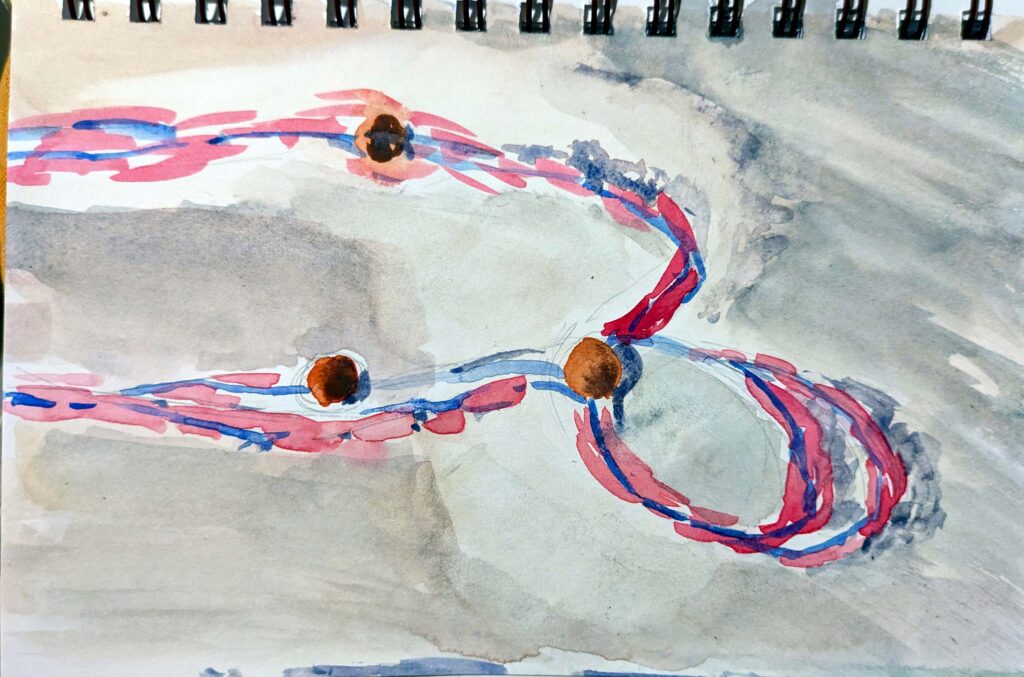

I’ve done just a few watercolor sketches along the shores at Gozo. They’re all fleeting and for my own amusement. Sketching (in pencil or paint) is how I observe my surroundings; serious painting for posterity is another matter entirely.

Malta and Gozo are the crossroads of the western Mediterranean. There are seven known megalithic sites on the two islands. The prehistoric civilization of Malta lasted a thousand years, starting around 4000 BC. We’ve burrowed deeply into this history; so far, we’ve visited the underground burial chambers of Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum and the Ħal Tarxien Prehistoric Complex on Malta, and the Ġgantija temple site on Gozo. Like so many others, I am mystified and humbled by the engineering, particularly the mathematical precision of the hypogeum’s Holy of Holies. But it is the small art objects that I find the most moving.

How does Malta’s neolithic art relate to the rest of the ancient world?

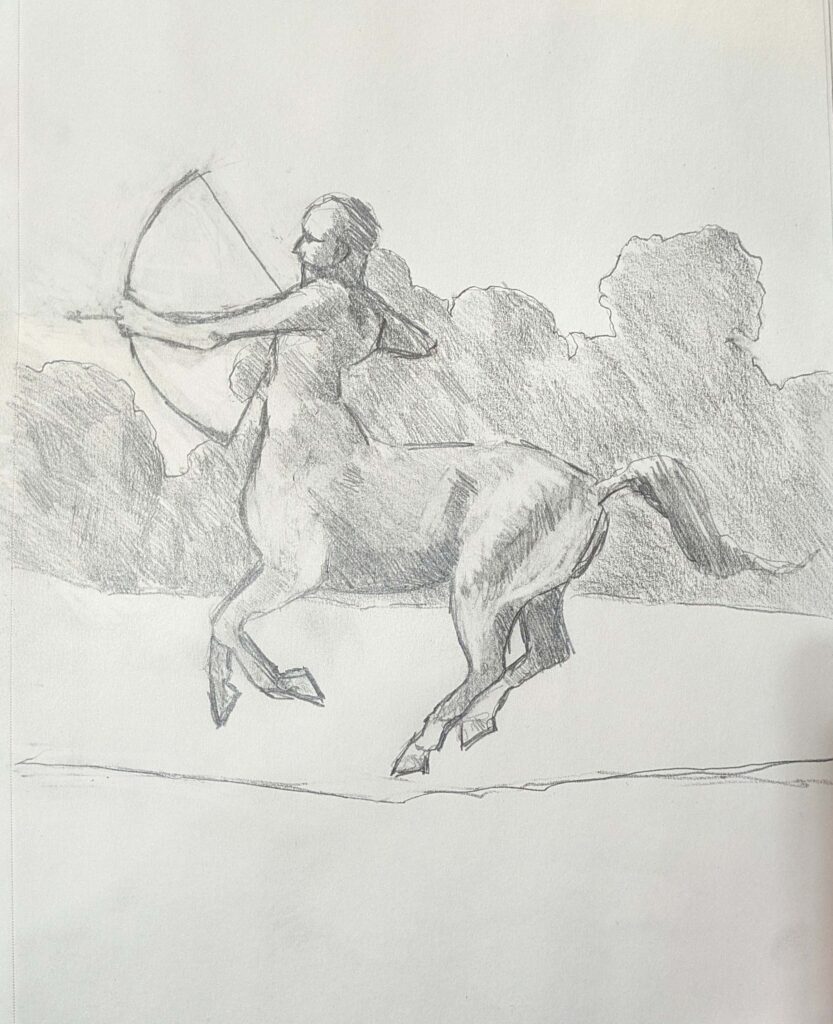

Western art is said to have started with Minoan and Cycladic art, both of which arose around the same time as Malta’s neolithic civilization. Since Malta is only about fifty miles from the coast of Sicily, that’s no surprise. Ġgantija had flint tools that could only have been acquired through sea-trade.

The earliest mariners had rafts, dugout canoes, and hide-covered coracles; sail-power was not introduced to the western Mediterranean until much later. The Mediterranean is a famously tempestuous sea; trade in small human-powered boats must have been a terrifying business.

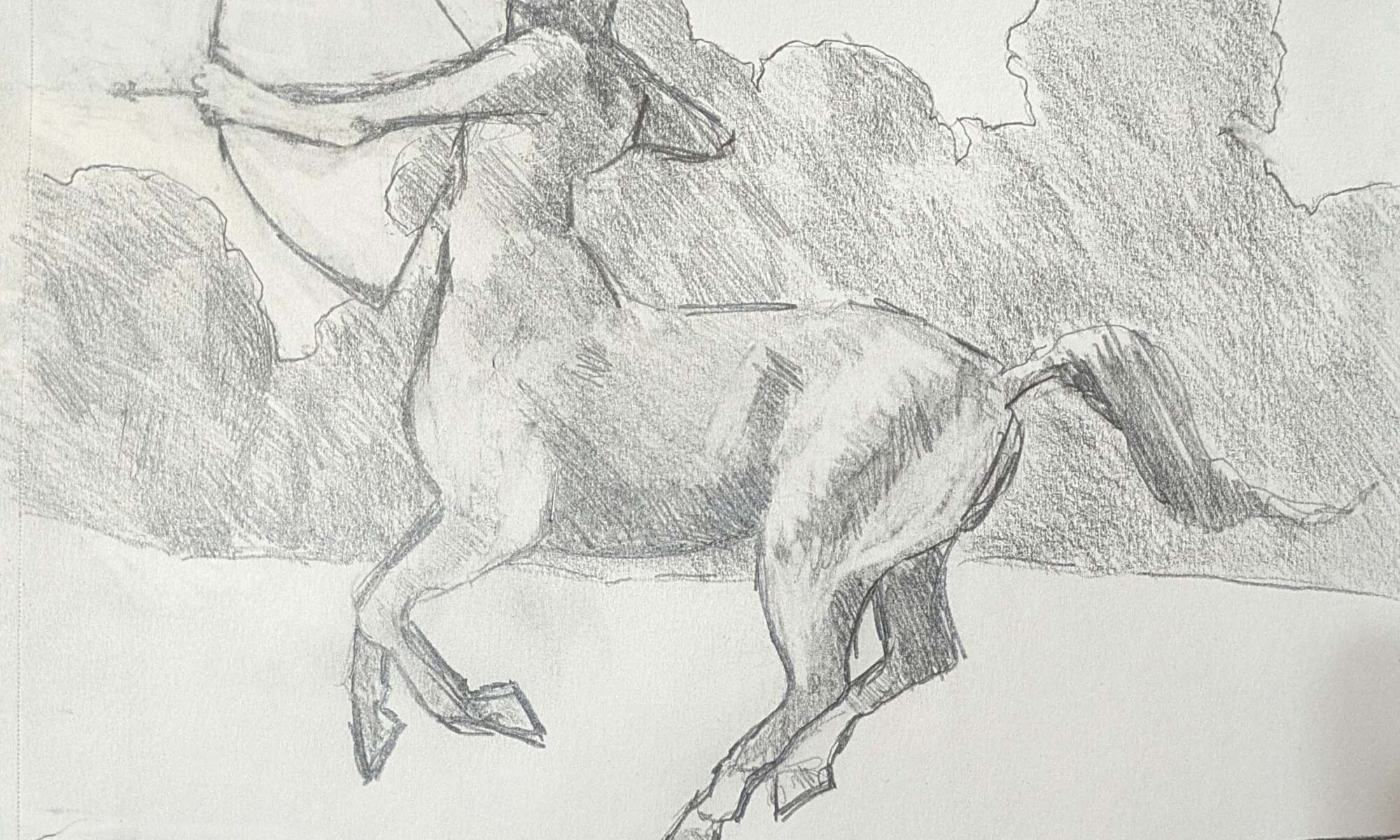

Artists like me

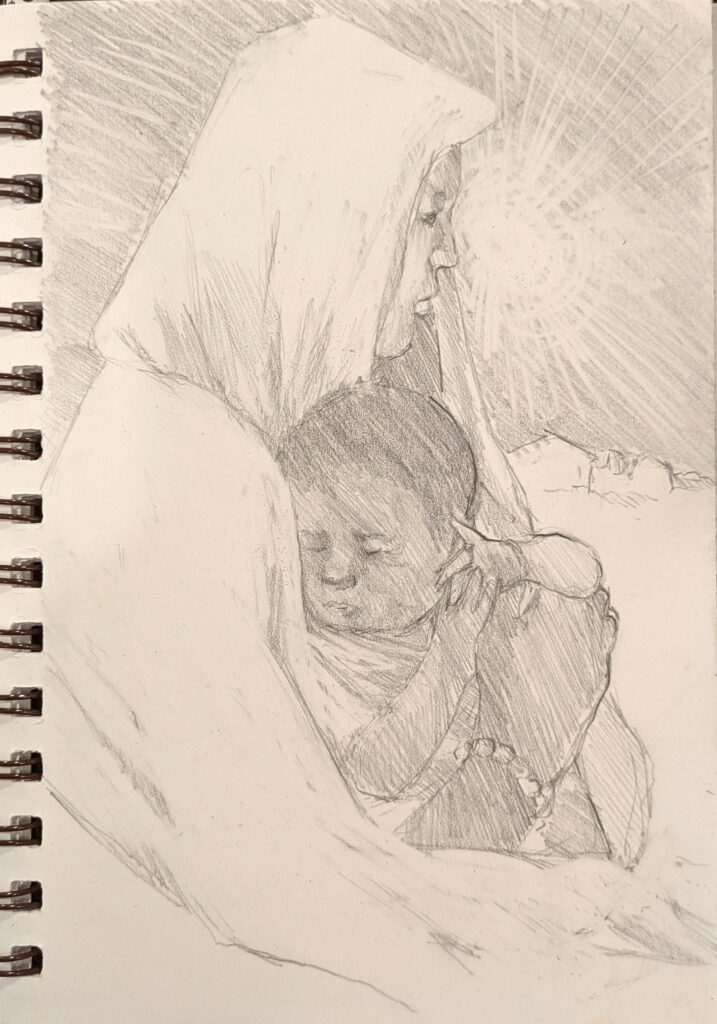

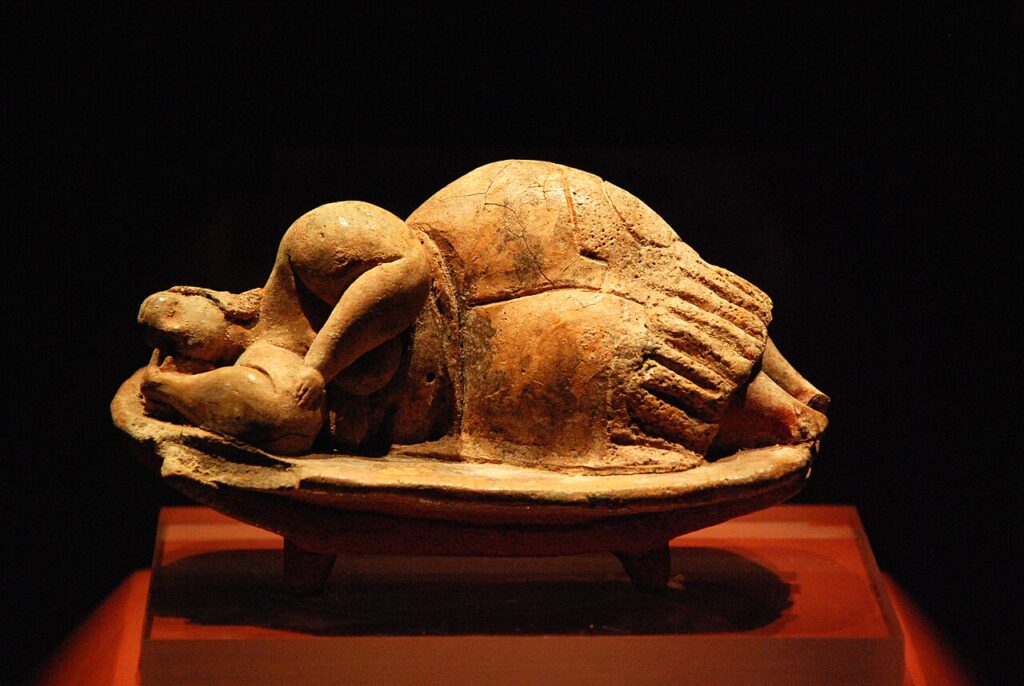

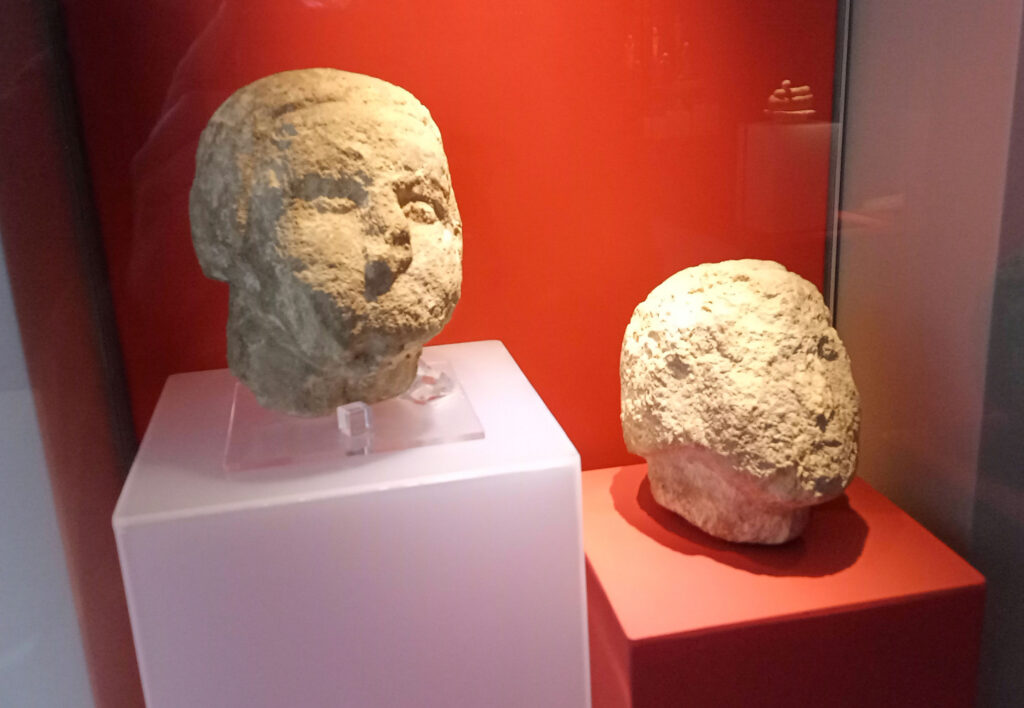

At Ħal Tarxien, there is a bas-relief of two fine bulls and a sow. It might have been ceremonial or it might have just been very fine kitchen décor. (Archaeologists have a tendency to explain away everything they don’t understand as being religious.) There are two half-size heads at Ġgantija with such poignant expressions that their feelings are visible through the weathering of five millennia. There are also figurines that tell us the ancients of Ġgantija looked much like modern Europeans. There are miniscule figurines carved of cow toe bones, and bead necklaces just for fun.

Each of these items was made by an artist like me. Similarly, artists like me painted the red ochre patterns on the ceilings and walls of the hypogeum, and carved the whorls in the temple sites.

Art requires that a civilization have leisure time. There must be time for artists to develop their craft, and spare resources to support those artists. There must be leisure time for audiences to look at and appreciate art. Societies that can produce art are civilized societies.

All that is left of neolithic art is that which was set in stone or pottery. There’s no trace left of painting, textile art, dance, or music. However, if sculpture existed, we can presume those other forms existed as well.

Likewise, the names and personalities of the creators are long gone—but, almost miraculously, their creations live on.

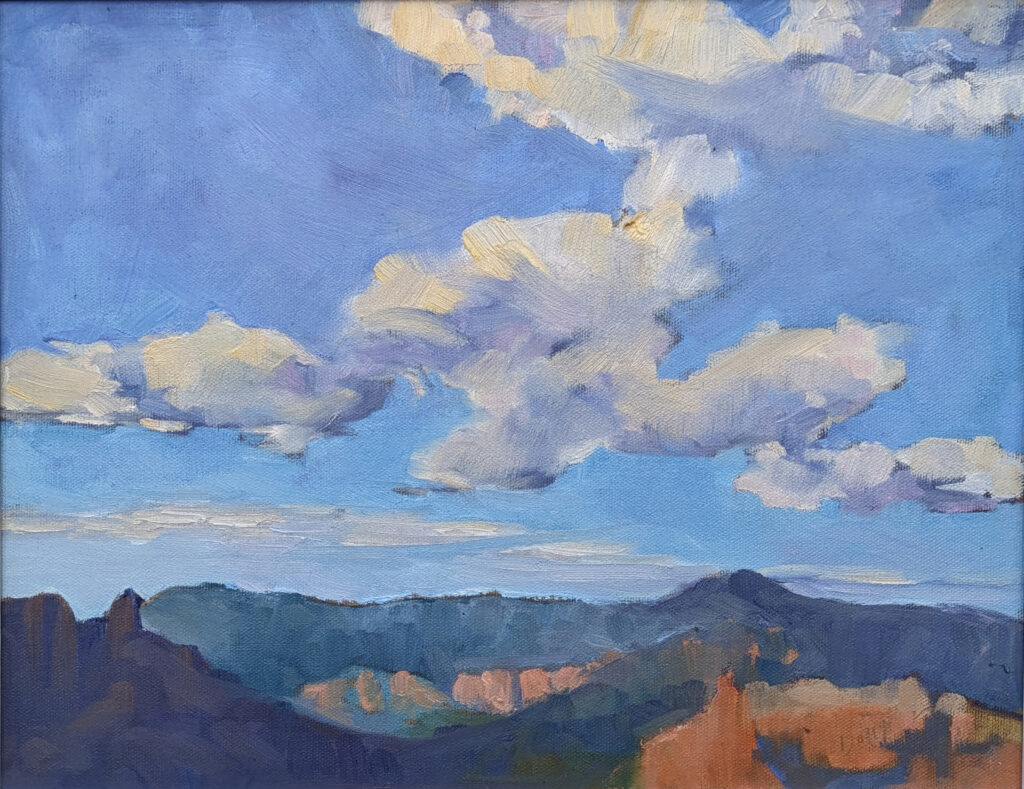

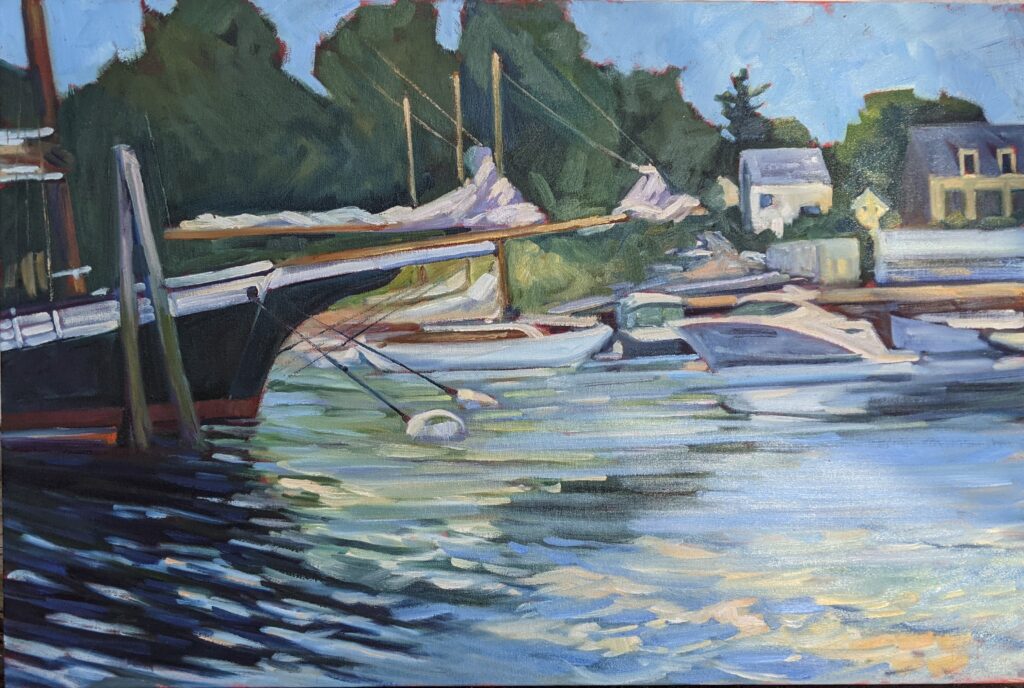

This spring’s painting classes

Zoom Class: Advance your painting skills

Mondays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 28 to June 9

Advance your skills in oils, watercolor, gouache, acrylics and pastels with guided exercises in design, composition and execution.

This Zoom class not only has tailored instruction, it provides a supportive community where students share work and get positive feedback in an encouraging and collaborative space.

Tuesdays, 6 PM – 9 PM EST

April 29-June 10

This is a combination painting/critique class where students will take deep dives into finding their unique voices as artists, in an encouraging and collaborative space. The goal is to develop a nucleus of work as a springboard for further development.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.