Yesterday my friend Barb and I peered at Night Hauling, a 1944 tempera painting by Andrew Wyeth. “I’ve lived here all my life and I’ve never seen bioluminescence in the sea,” she said.

“Well, I also imagine at that time most people were using lobster boats with engines,” I countered.

“Not if they were stealing traps,” she said, and we both laughed.

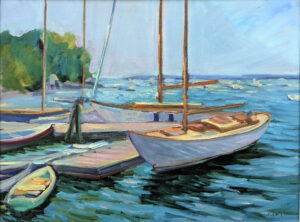

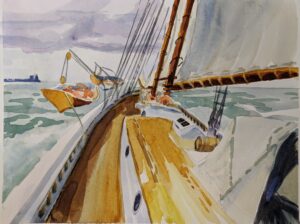

In 1944, Wyeth was still trying to figure out how to emerge from the shadow of his famous father. It would be four more years until Christina’s World proved he was ‘not your father’s Oldsmobile’. Night Hauling is magical realism built on an utterly firm foundation of realistic drawing and painting; it’s what NC Wyeth was famous for and what his son and grandson would carry forward in American art.

The Wyeths all had individual and personal visions. Grandpa and grandson are insouciant and entertaining; Andrew is melancholy but with humor. Their message is so clear because it rests on perfect painting chops. Mediocre painting never gets in the way of what they’re trying to say.

The meaning of meaning

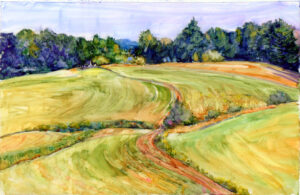

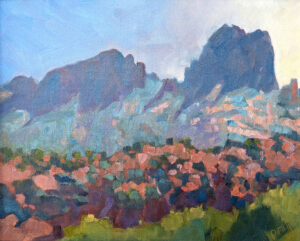

Great historic landscape artists like John Constable or Claude Monet were doing more than simply recording scenes. There is science, observation, and a great deal of thought behind their work. In addition, there’s a well-realized ethos. It could be spelled out as with the artists of the Salon des Refusés, or it could be subtle, but it is always there.

I realize we haven’t got easy themes like American Exceptionalism at our disposal anymore, and much art is just too politicized to be bearable. However, no painting should be without meaning, or it may as well be wallpaper. That’s why I constantly ask the question, “what were you trying to say in this painting?”

Bad Art for Sale Near Me

“I count twenty paintings that this group did in one day,” a reader wrote last week. “The event went on for a week, so that’s a hundred paintings! You know all of them can’t be particularly good.” I didn’t need him to add that, because he included a photograph. The word I’d use to describe them is pedestrian, and that’s possibly being generous.

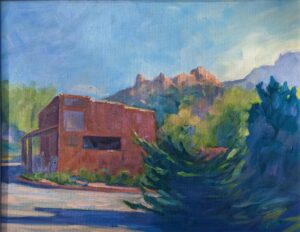

“They’re all going on sale, too,” he added sadly. I never get too bent about Bad Art For Sale Near Me because the people who can’t tell the difference are not my audience. But he’s right; it does devalue painting when so much mediocre stuff is on the block. I love plein air events but I think they’ve hit the point of oversaturation, and now I carefully pick which ones I do.

What do you do with the duds?

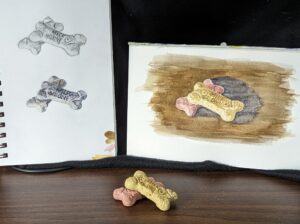

I firmly believe that the only way you get better is to keep painting, lots. My old friend Marilyn Fairman used to say, “I saved another canvas today,” after she scraped out what she’d worked on all day. I never do that because I think it keeps me repeating what I’m comfortable with. But I also don’t paint over old paintings; they have impasto that’s tough to cover. Needless to say, I have lots of duds. If you’re doing it right, you should too. And you should not confuse your mediocrities with your best work.

We often change our mind about work we’ve finished. I recently found something I dislike in a painting I used to love. I’ve been teaching color bridging recently, and I realized that one passage of that painting would have benefitted from it. (No, I’m not going to edit it. That way lies madness)

I used to have an annual party where I’d saw through every painting I hated in my inventory. I have a new idea to recycle them. But the important thing is to recognize that you’ve grown and changed, and to stop letting your mediocrities drag down the gems in your work.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.