Painting teachers can sometimes focus on the negative, because it’s part of our job to point out deficiencies. However, there is a lot we can learn by asking our students, “What are you good at?”

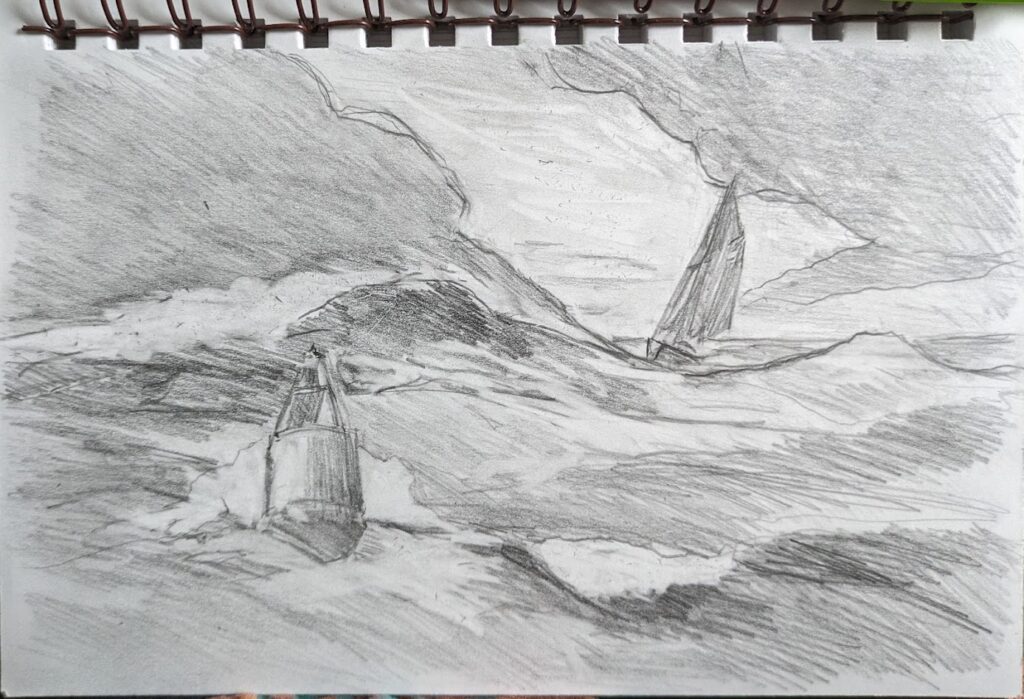

I’ll go first: I’m logical, good with numbers, and I’m disciplined. In art terms, I’m a good composer and draftsman and I’m intrepid. See, that wasn’t too hard.

Your turn: what are you good at?

Name three qualities that are general and three related to your art. I can easily see a relationship between my strengths on and off the canvas. What about you? Are your strengths as an artist related to your strengths as a person?

No, it’s not bragging

I’m not asking you to talk about your awesomeness to everyone you know. We humans all perseverate on our weaknesses, and as an artist you’ve chosen a career with lots of knocks to the ego. A realistic idea about your strengths is a good counterweight to the negativity of the art world.

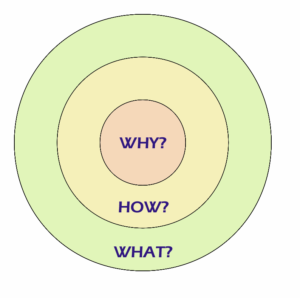

Why is this important?

Looking at our strengths is an effective learning tool. Reflecting on our strengths helps us understand ourselves better. It allows us to recognize where we excel and what comes naturally to us.

Knowing our strengths boosts our confidence. When we are aware of what we’re good at, we feel more capable and empowered to tackle daunting challenges. Confidence can be a driving force in achieving our goals.

Understanding our strengths also helps us set realistic and achievable goals. By leveraging our strengths, we embark on projects that align with our abilities. That increases our chances of success.

Focusing on our strengths enables us to further develop and refine them. Continuous improvement in areas where we excel can lead to greater mastery in those areas. That in turn enhances our overall competence.

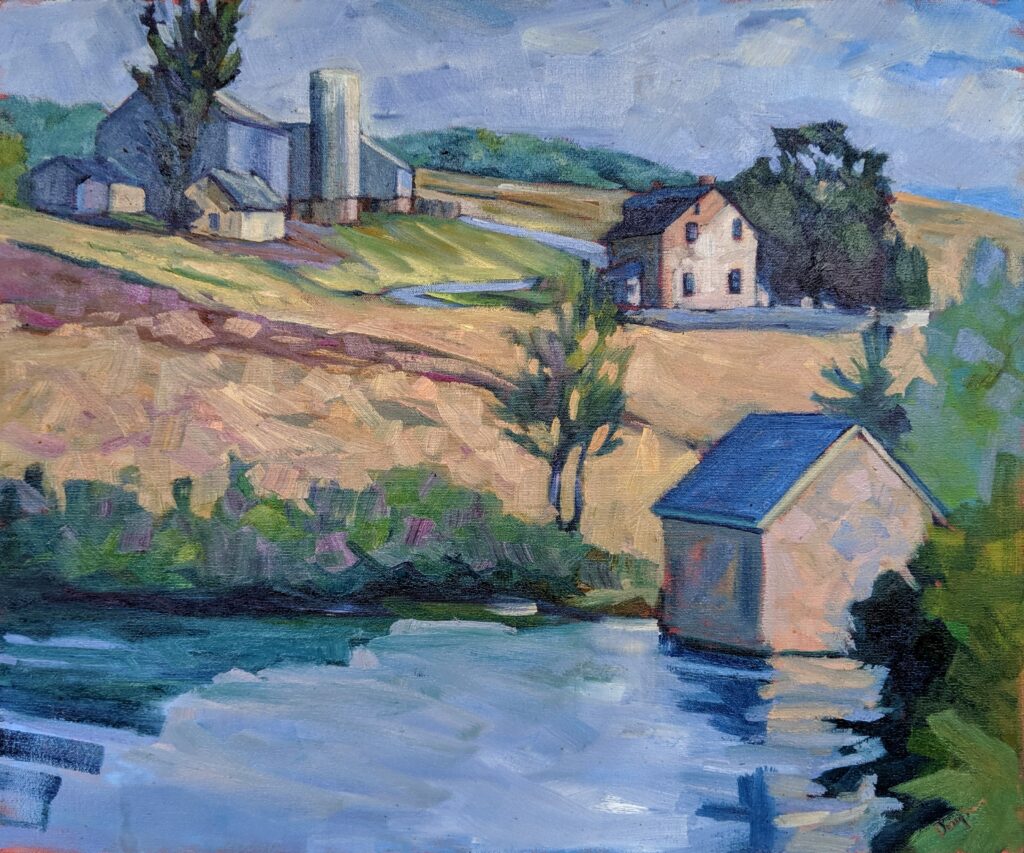

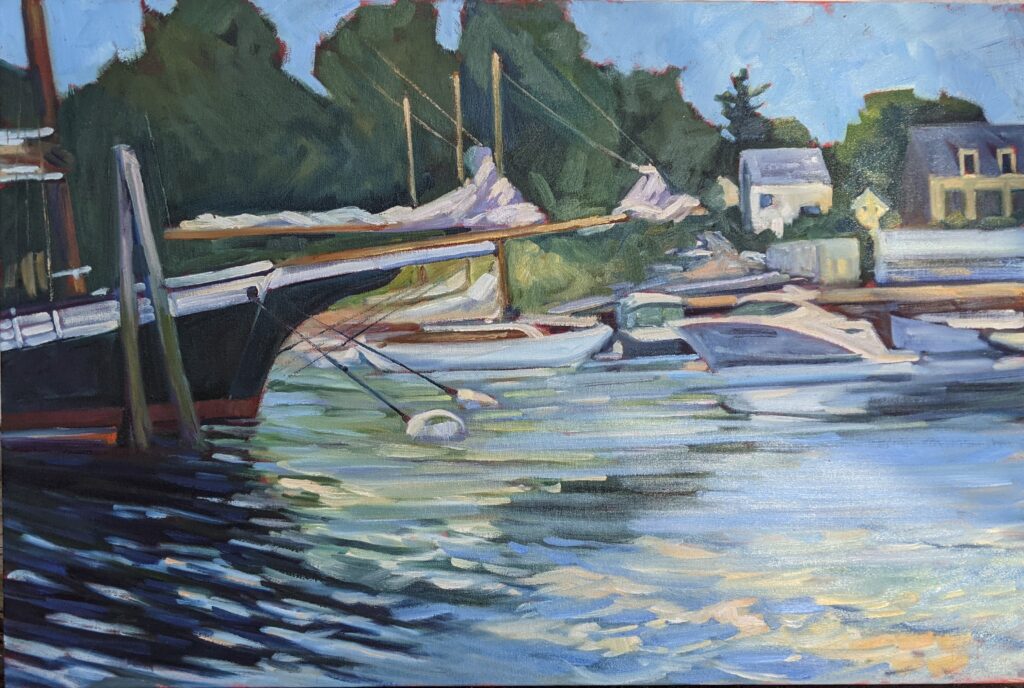

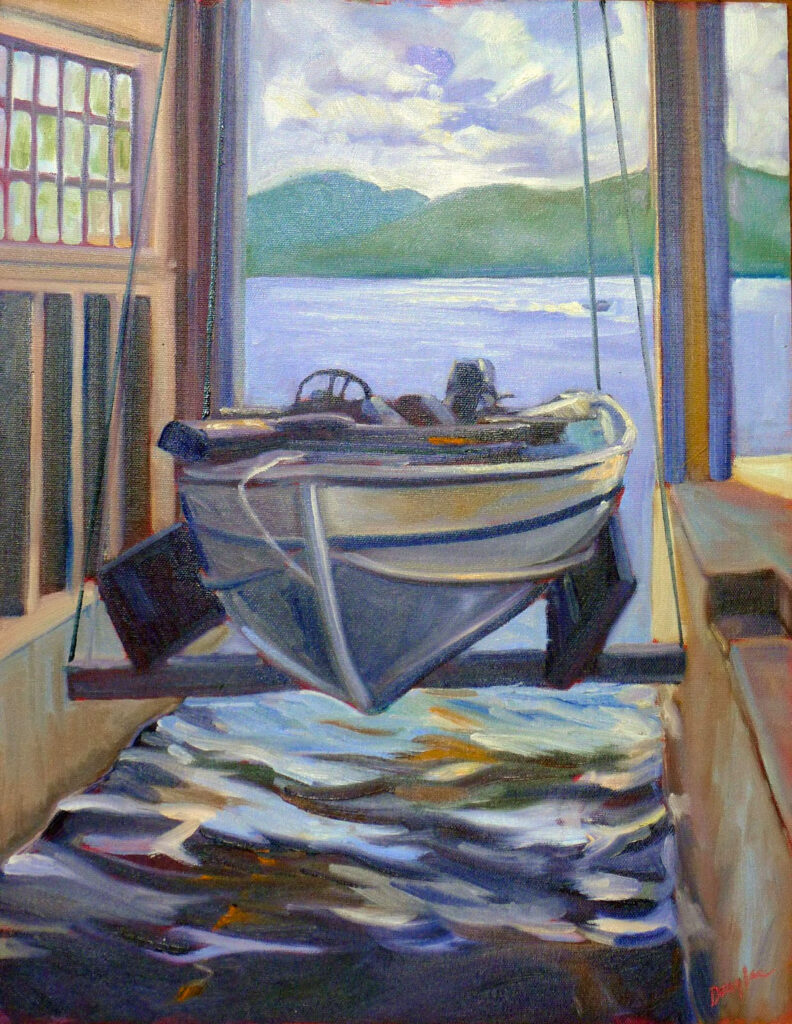

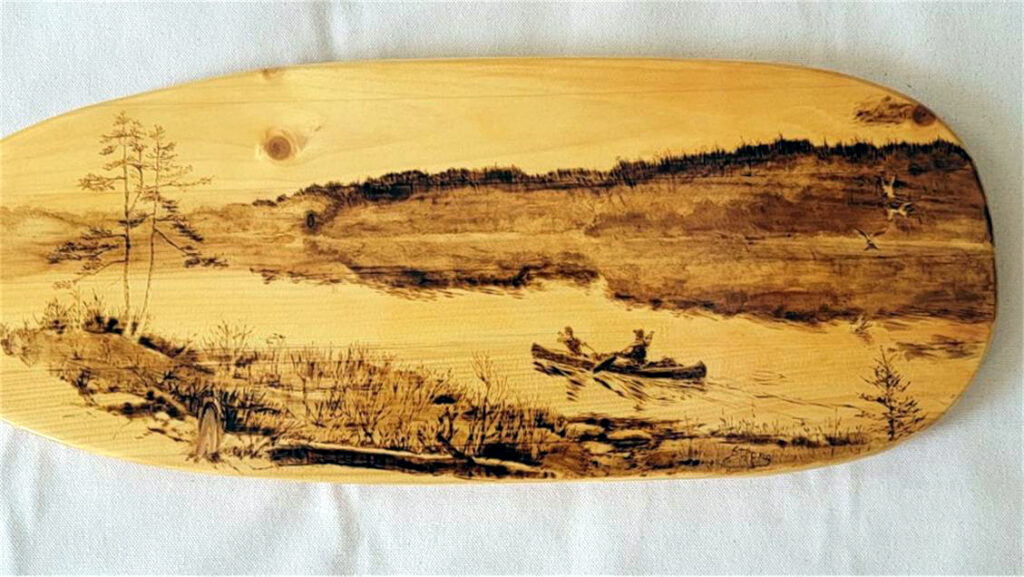

It also allows us to collaborate more effectively with others. I have a show hanging at Lone Pine Real Estate this season. It’s a good symbiotic mesh between experienced brokers and an experienced painter. I recognize their strength at attracting a clientele, but I also understand that my strengths in painting houses and boats gives them subject matter that meshes with their mission.

Above all, recognizing our competence develops resilience. All of us sometimes get to a point where we think, “I can’t do anything right.” Knowing our competence helps us navigate periods of self-doubt or rejection.

Above all, it feels good

Not beating ourselves up all the time is such a relief. Art (and life) is just more fun when we feel good about what we’re doing. What we focus on, we (to some degree) become. As King Solomon wrote some 3000 years ago, “for as he thinks within himself, so he is.”

If you’ve got the courage, answer the question “what are you good at in art and in life?” below. (I promise to not tell anyone.) Can you see a relationship between the two? Can you see a way those strengths can be a building block to future success?

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.

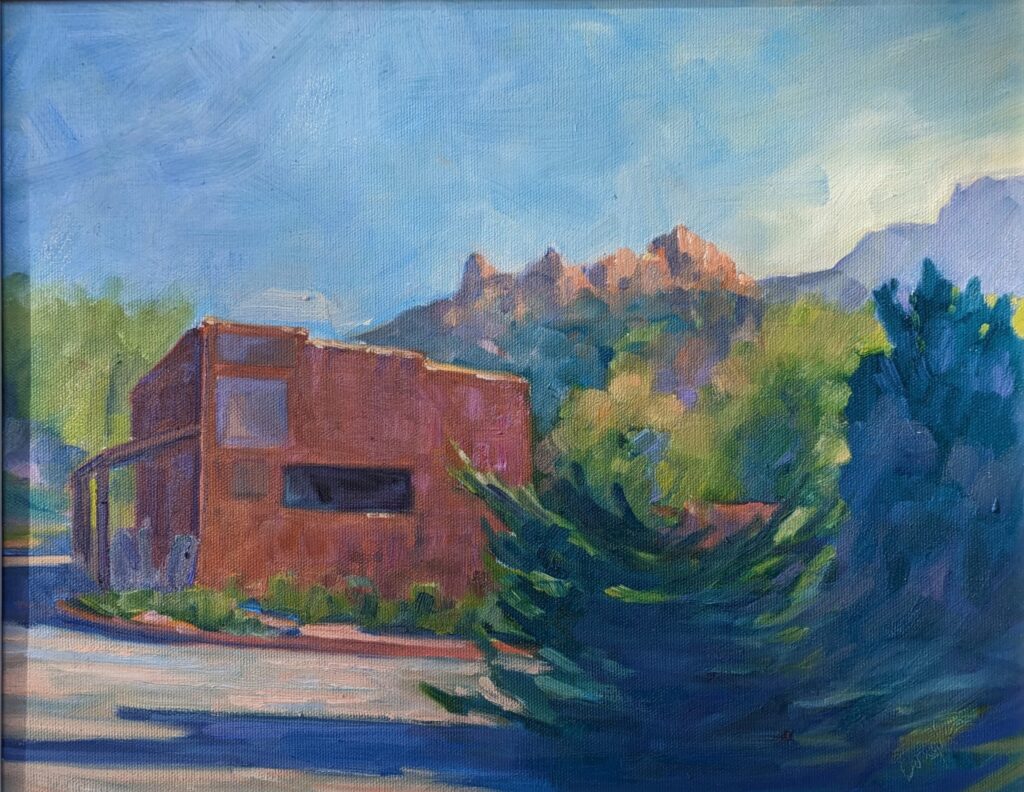

Footnote: the Red Barn Gallery in Port Clyde, ME, is looking for an artist to join for the 2024 season. It’s a cooperative gallery so you must be able and willing to work shifts there. Having done it myself, I can tell you there are few places more pleasant in which to spend a summer afternoon. The application is here.