Given a choice of painting the same subject en plein air or in the studio, I’ll always go outdoors. I think it makes for better paintings, but it’s also a better experience.

In general, painting from life is superior to painting from photos. Photography works out the subject, composition and color for you, and it’s hard to escape its bossiness. People can work from life within the genres of still life, interiors and figure painting, but the natural world is the biggest and best source of observed reality.

Full immersion

Being surrounded by the environment that I am painting is a full sensory experience. Yes, that can include insects and jackhammers, but it’s more likely to include sweet smells on soft breezes and birdsong.

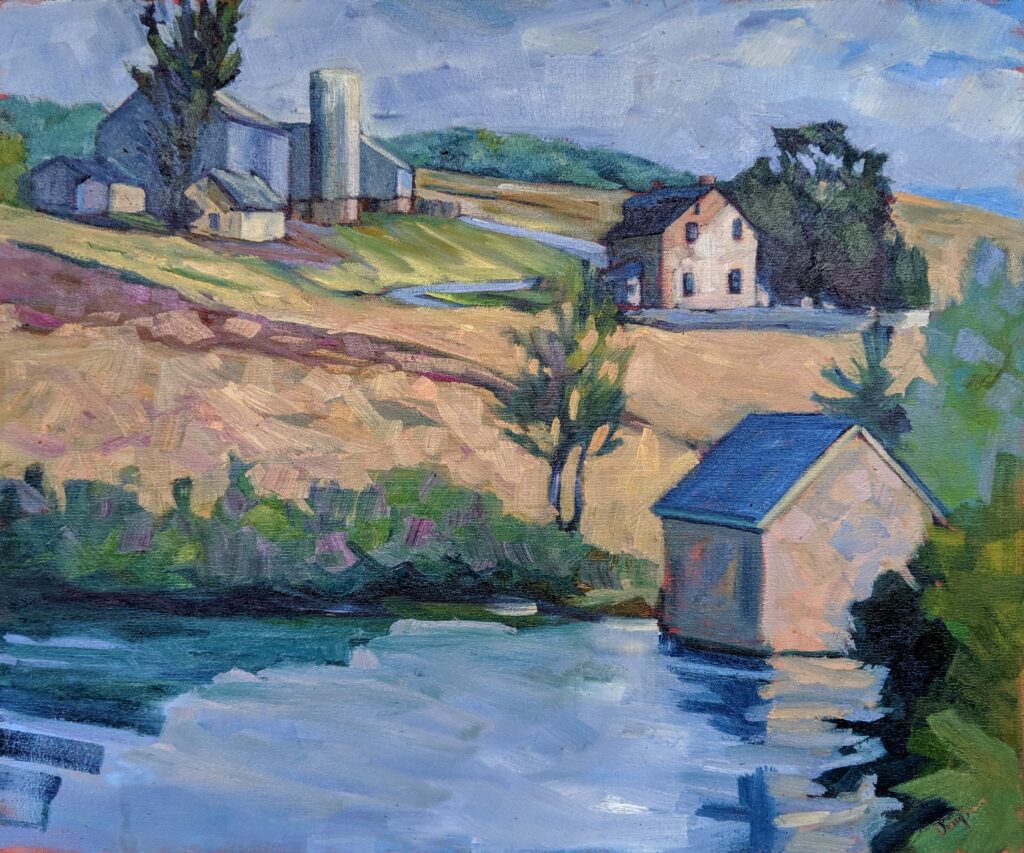

For every painting location, there are many potential subjects and compositions. I once stood on a hillside and painted in each cardinal direction. I didn’t begin to plumb the possibilities of that site.

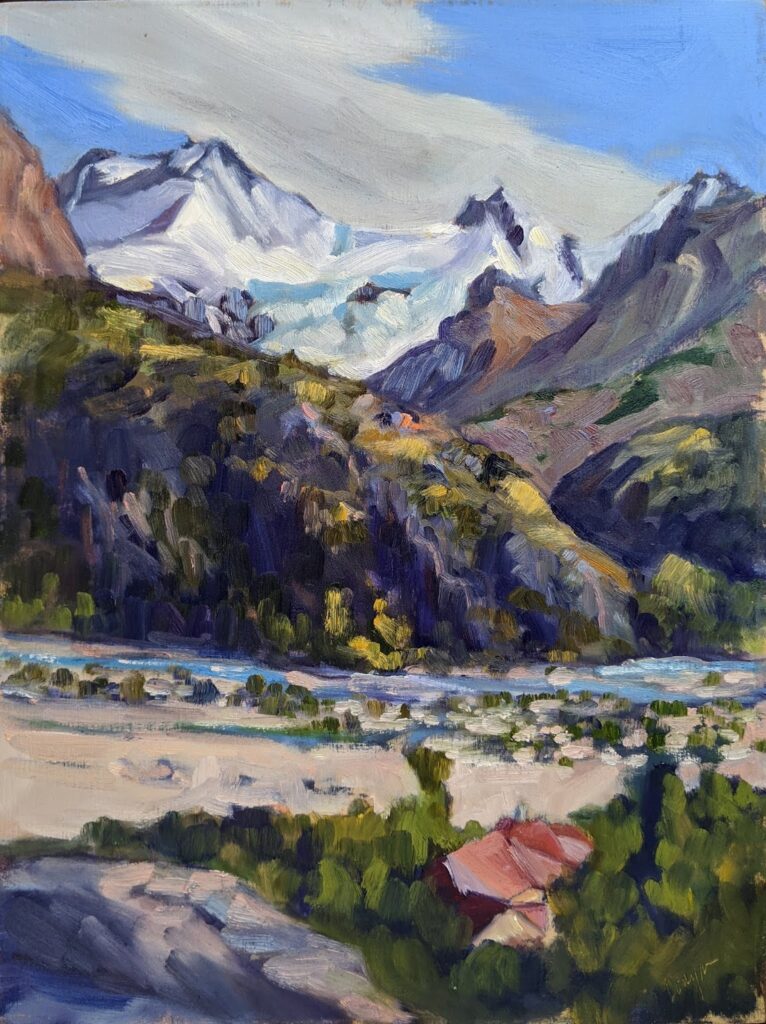

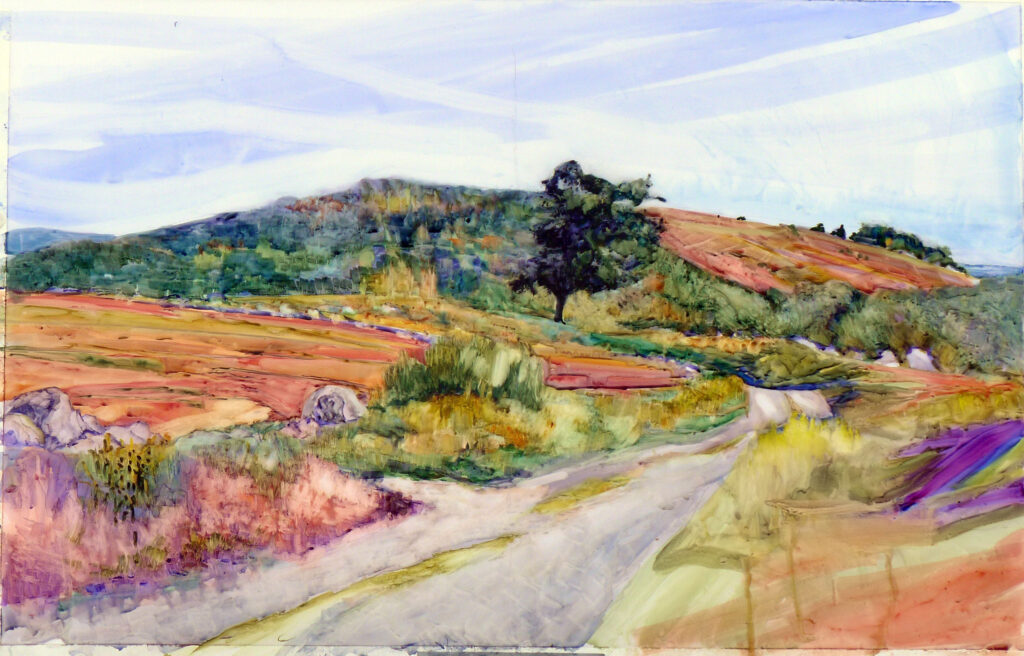

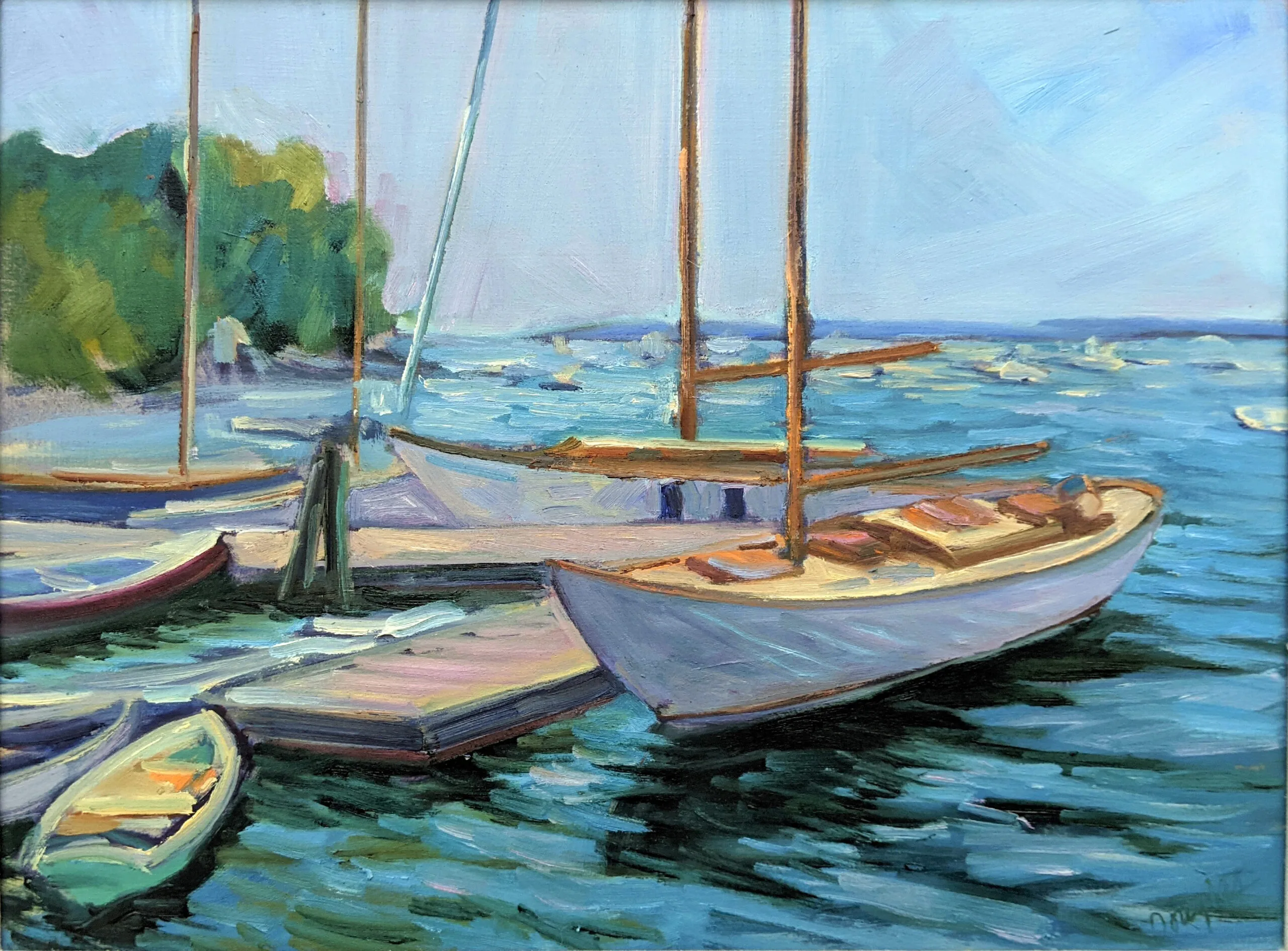

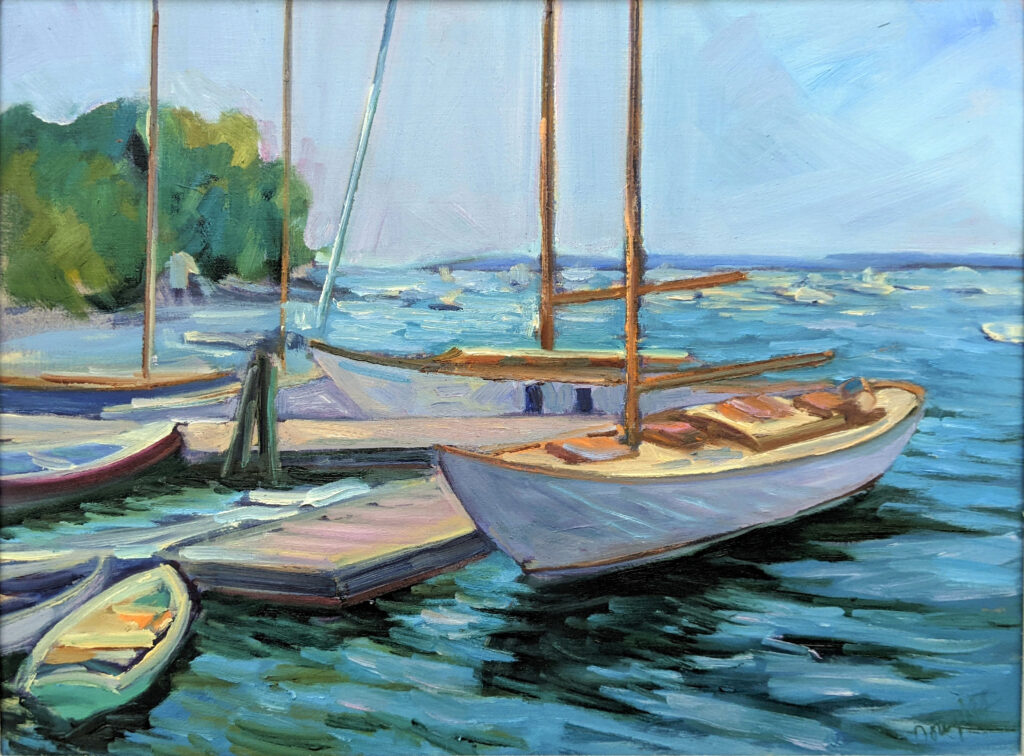

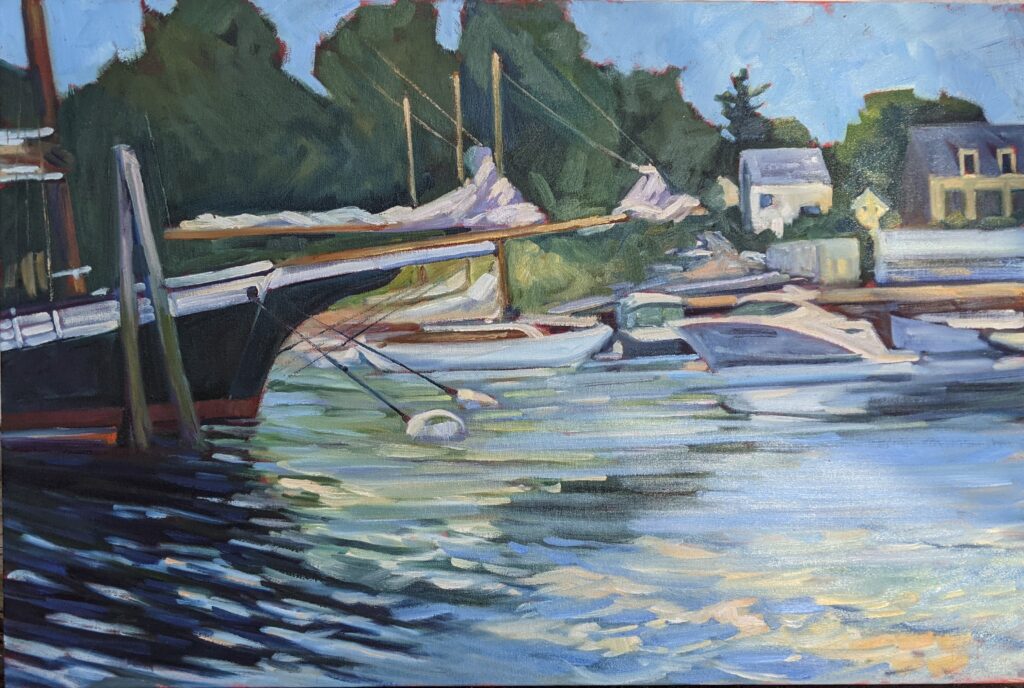

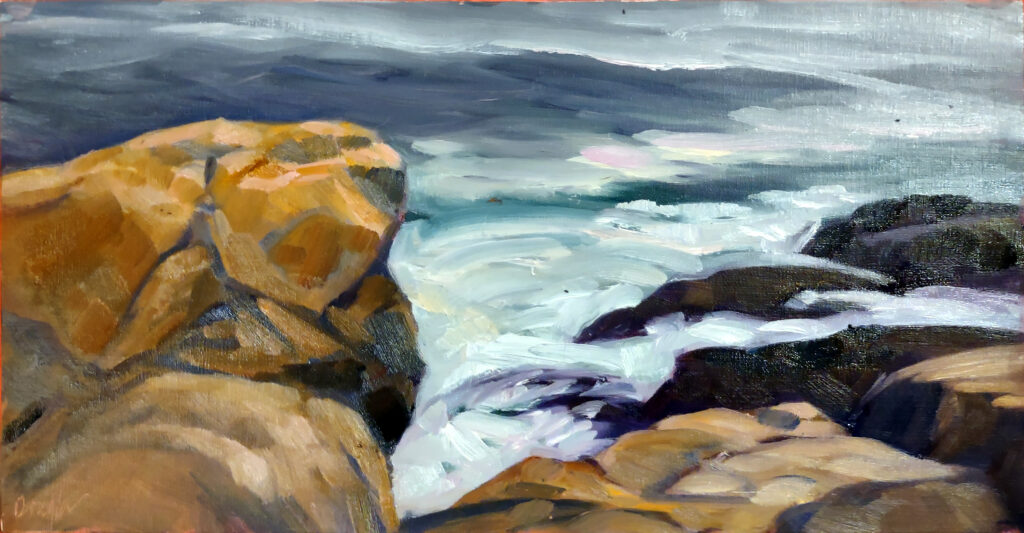

Painting outdoors lets me experience natural light in its full color spectrum. Look at any photograph of a scene you know and love, and you’ll quickly realize how photos flatten and distort color. And painting indoors under bad lights is just horrible for your color perception.

I’ve painted in rainstorms, in withering heat and humidity, and in blasting Arctic cold. More commonly, I go out when the weather is moderate, but its changeability has taught me ways to control and adapt my painting, and above all, to work fast.

The great outdoors

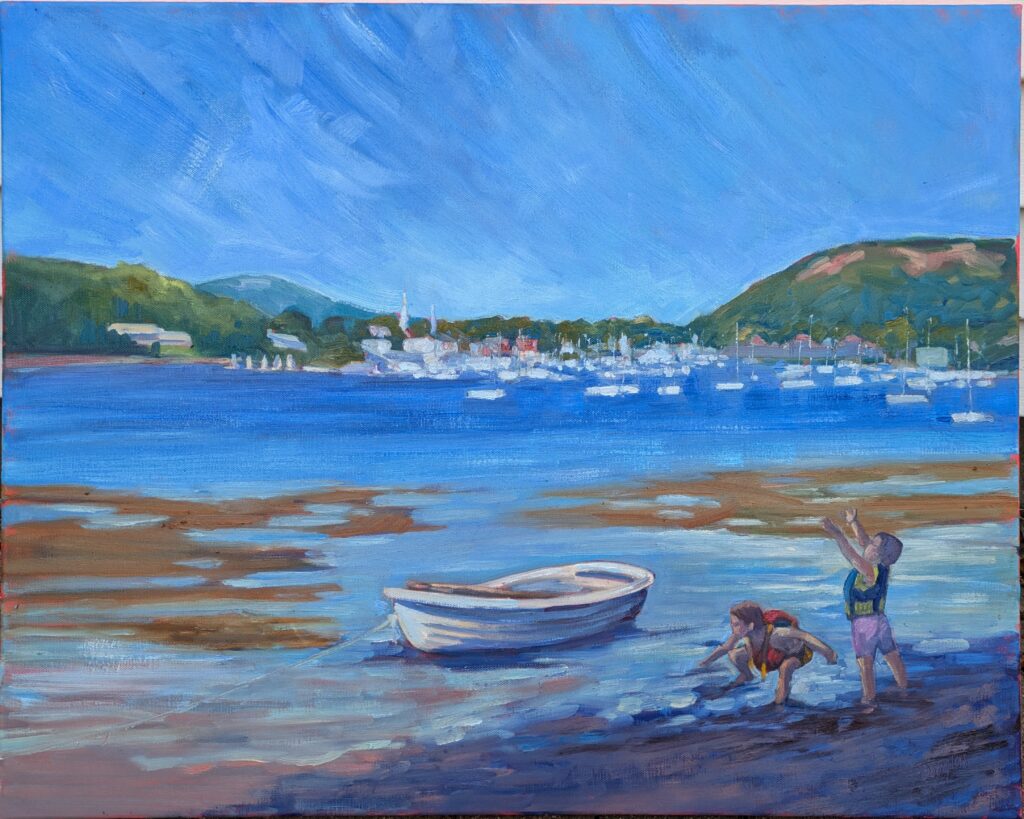

Being an outdoorswoman to my bones, I appreciate that plein air painting lets me work in beautiful places. Standing quietly in one place for hours allows you to see it in a different way from that of the typical tourist. People love the natural world but due to issues of time, money and mobility, they can’t always get to it. (I remind myself to be thankful every day I can climb Beech Hill.) Plein air painting is a way to bring nature to a world that’s increasingly insulated.

On the best of days, you can text a photo of a wood lily or an elk to a friend. That’s humbling.

Some of my best friends are plein air painters

I know plein air painters from all over North America. The crush of plein air events means we’re often thrown together in ways that forge deep friendships. I might not see them for years, but we fall back into our old rhythms of friendship very easily.

I see this in my workshop students, too. There is something about standing on a rock with the same people for a week that fosters closeness.

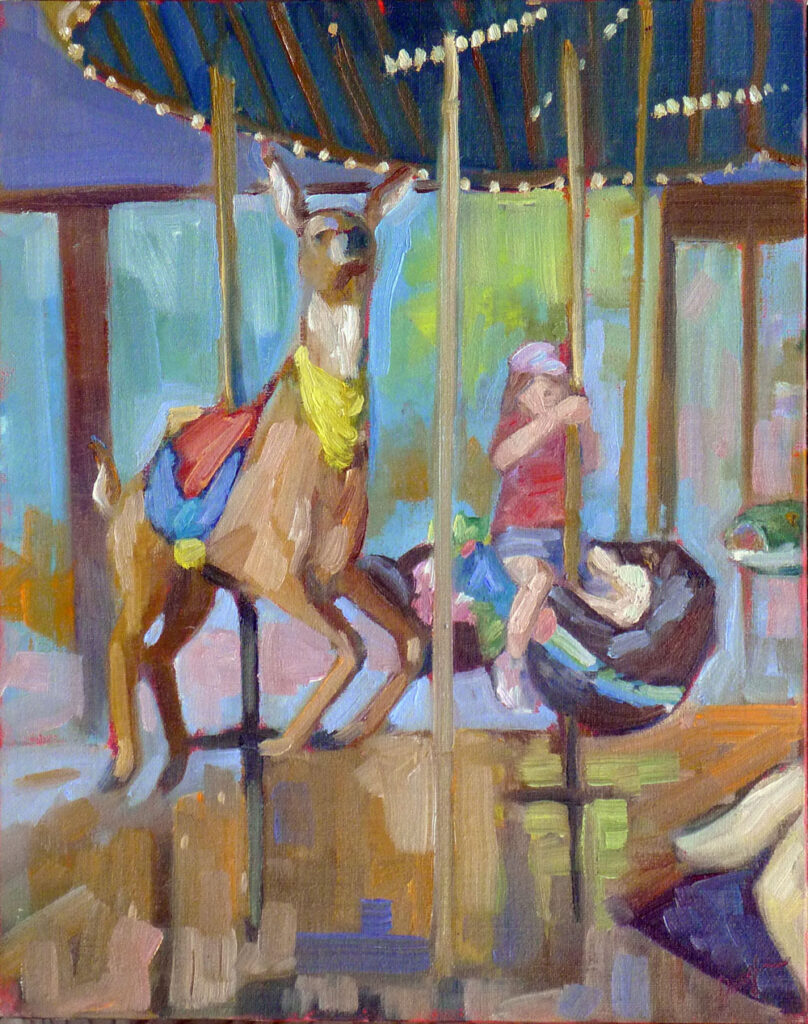

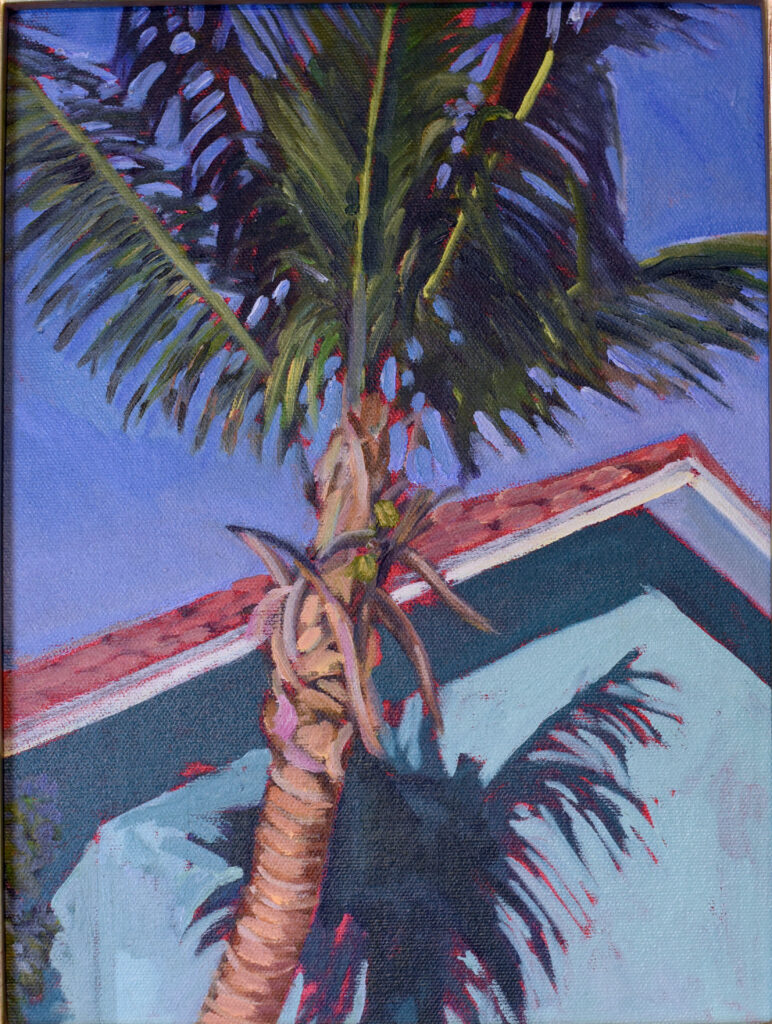

Plein air is not limiting

Some of my friends love painting architecture; some like painting in large cities (that used to be me). Some are attracted to the bleak industrial wasteland. Some like the high desert, and others like the ocean. I’m easy, myself; I love the landscape I’m with. But there’s no wrong subject in plein air. Beauty is everywhere, and as long as I’m still mobile, I’ll still seek it out.

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.