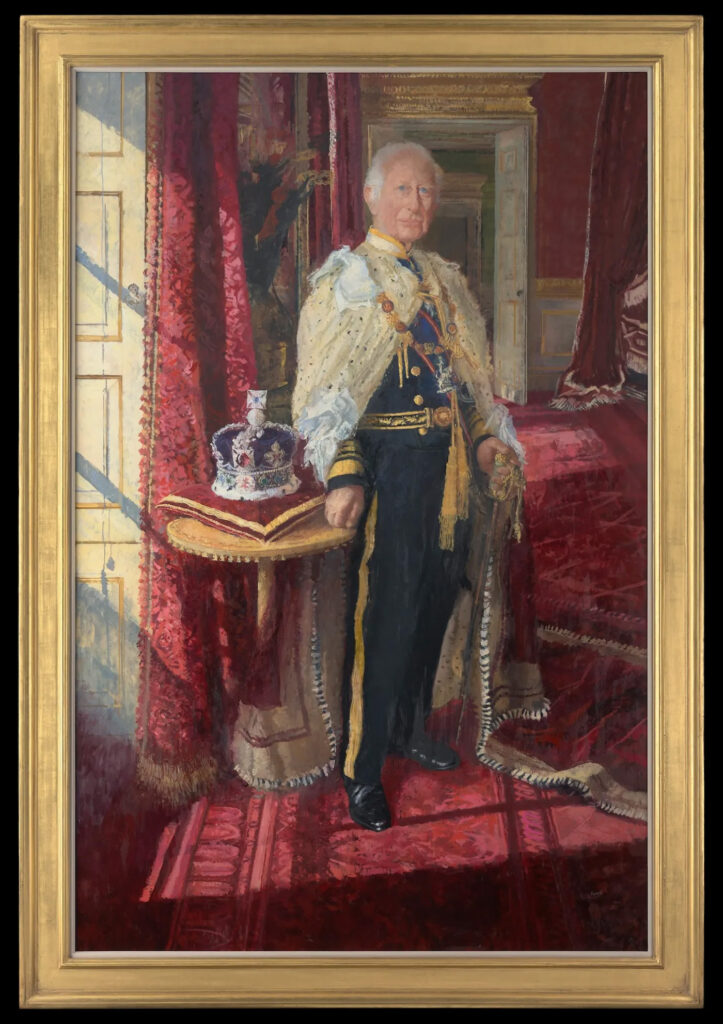

By the time you read this, King Charles’ and Queen Camilla’s coronation portraits will have been picked over by the media. They aren’t innovative, thank goodness, because official portraits shouldn’t be.

Camilla’s coronation portrait is more accessible, but then again, she takes the better photo. Her painting has long sweeping diagonals and painter Paul S. Benney has managed to give her a hauteur she never achieves in life. There’s just enough pattern in the regalia to set off the simplified form of dress and background.

Charles’ coronation portrait, by Peter Kuhfield, is more complicated, and I think that makes it a better psychological portrait. His regalia is wearing him, which is how I picture him each time he makes a public appearance in his three-piece grey suit, top hat, umbrella, tie pin, boutonniere, pocket square and glace shoes. He’s always dapper, but ever so slightly rumpled (unless he’s in a kilt). His clothes seem like outfits from another century.

In the portrait, his face is in shadow, without distinct modeling. He’s been struggling with cancer for two years. For Kuhfield to have captured that sense of fading away is insightful, sad and terrible.

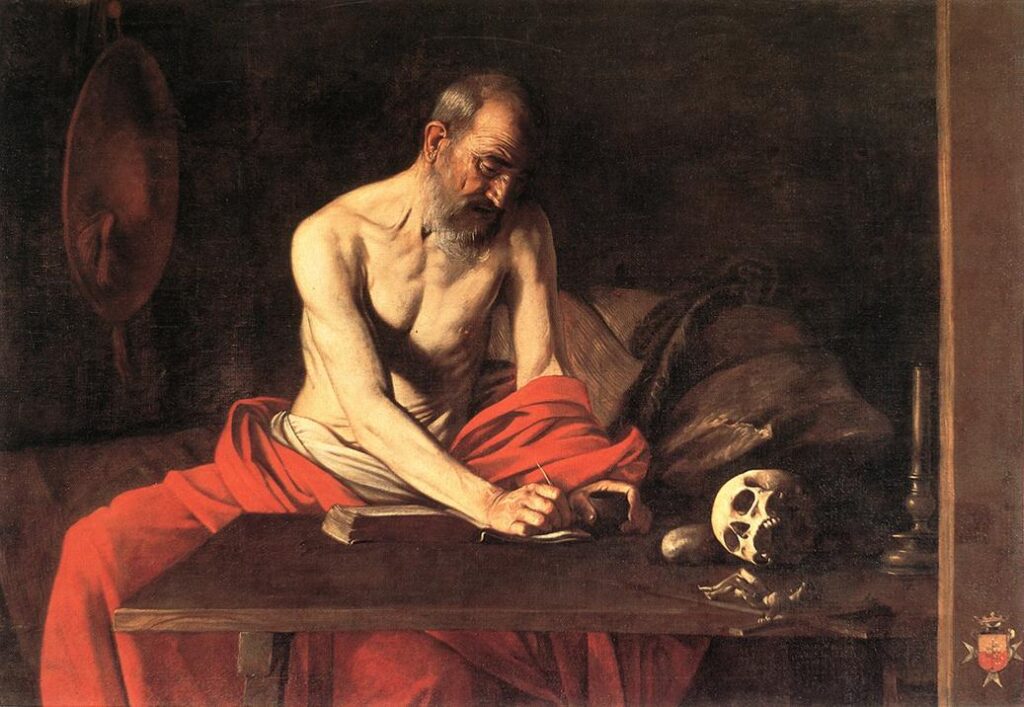

Pity the poor person tasked with doing a portrait of a king or queen. Portraits are difficult enough. Add to that the demands and demanding schedules of princes of the realm. Clothing and figure will done with stand-ins or mannikins (as was the case with Nelson Shanks’ portrait of Princess Diana).

Hans Holbein did a drawing of Henry VIII which was widely copied by other artists in lieu of getting the king to sit at all. In his older years, the king was infamously irascible, cruel, and intolerant, with a noted inclination toward murder. It’s no surprise portrait painters kept their distance.

Until the age of photography, all we knew about kings and queens was what we learned from their paintings. Thus we believe Anne of Cleves was beautiful because Holbein painted her that way. That was despite Henry complaining that, “She is nothing so fair as she hath been reported… [if] it were not that she had come so far into my realm, and the great preparations and state that my people have made for her, and for fear of making a ruffle in the world and of driving her brother into the arms of the Emperor and the French King, I would not now marry her. But now it is too far gone, wherefore I am sorry.” What a mensch.

Queen Elizabeth’s coronation portrait

Queen Elizabeth II had some real stinkers painted of her, among the worst being by Lucien Freud in 2001. Freud’s error, I think, is in trying to impose a psychological state on her portrait. A famously private woman, she wasn’t giving anything away to strangers. The best are the 1955 Pietro Annigoni portrait and Andy Warhol’s 1985 screenprint. Neither try to be something they can’t.

But it’s in her photographic portraits by fashion photographer Cecil Beaton that we see something of the woman behind the throne. Theirs was a long relationship. Elizabeth first sat for Beaton in 1942. Over the next three decades he photographed the Queen on many significant occasions, including her Coronation Day in 1953. But he also took pictures of her family life, and there’s an intimacy to his pictures that paintings don’t seem to capture.

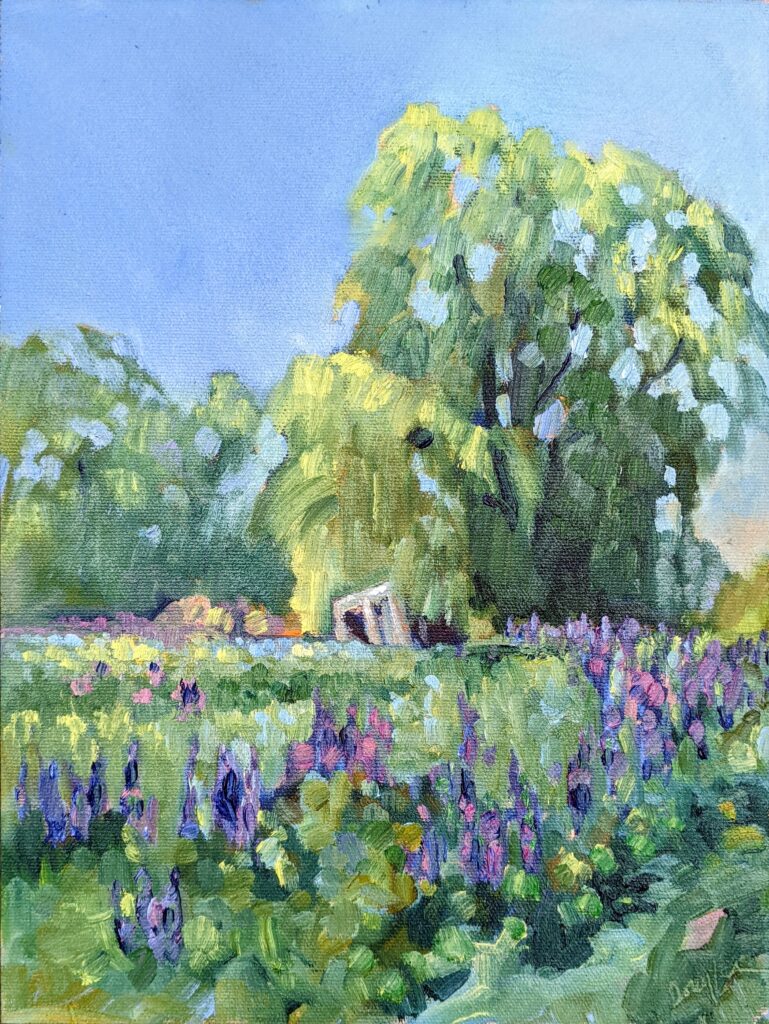

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

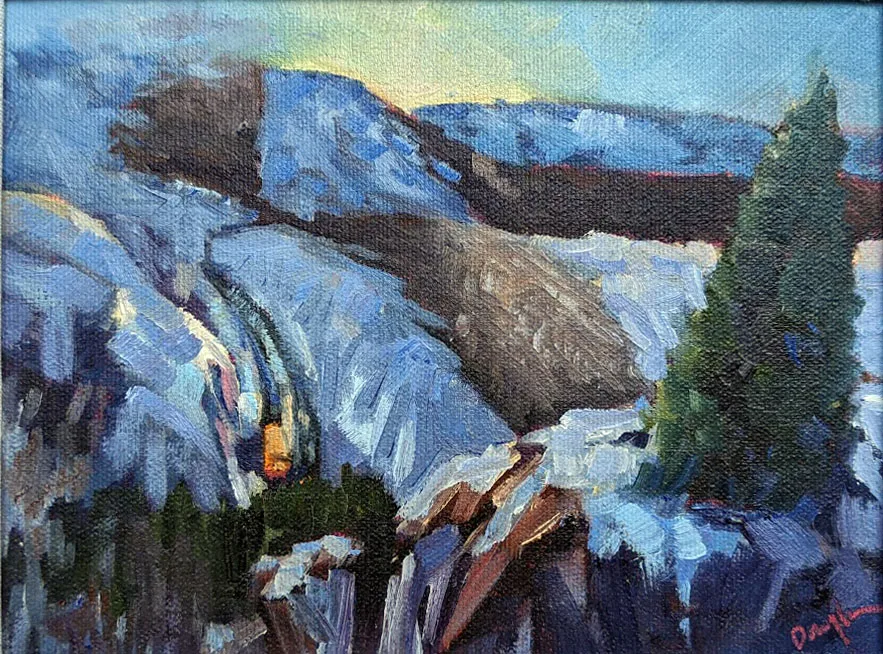

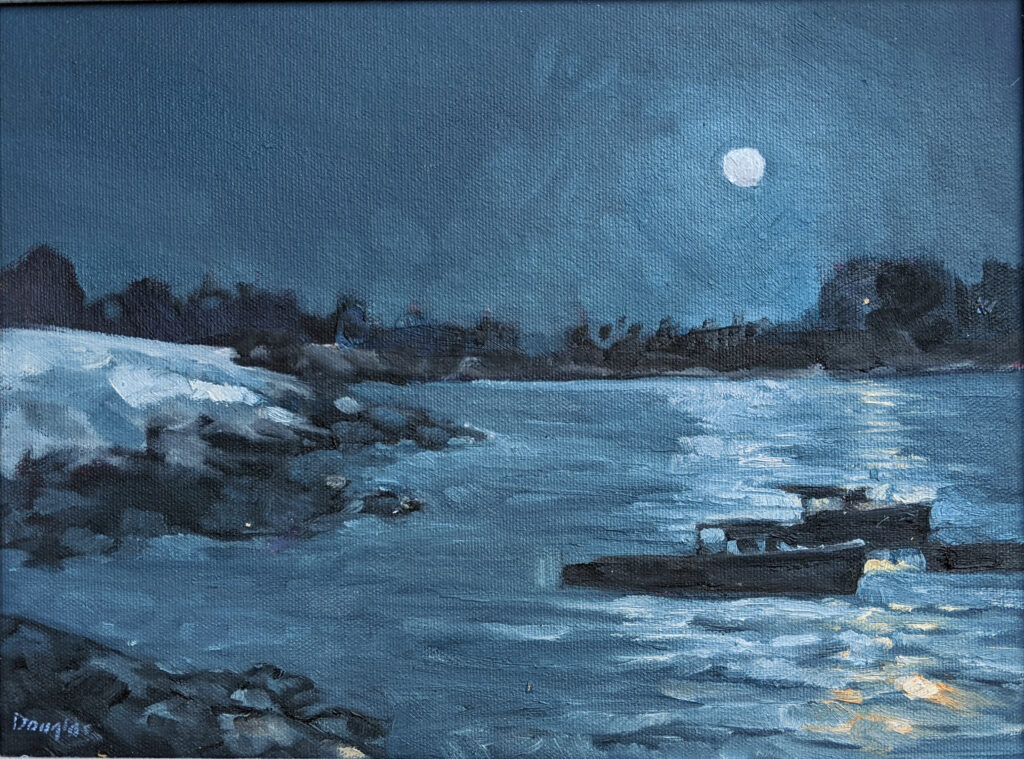

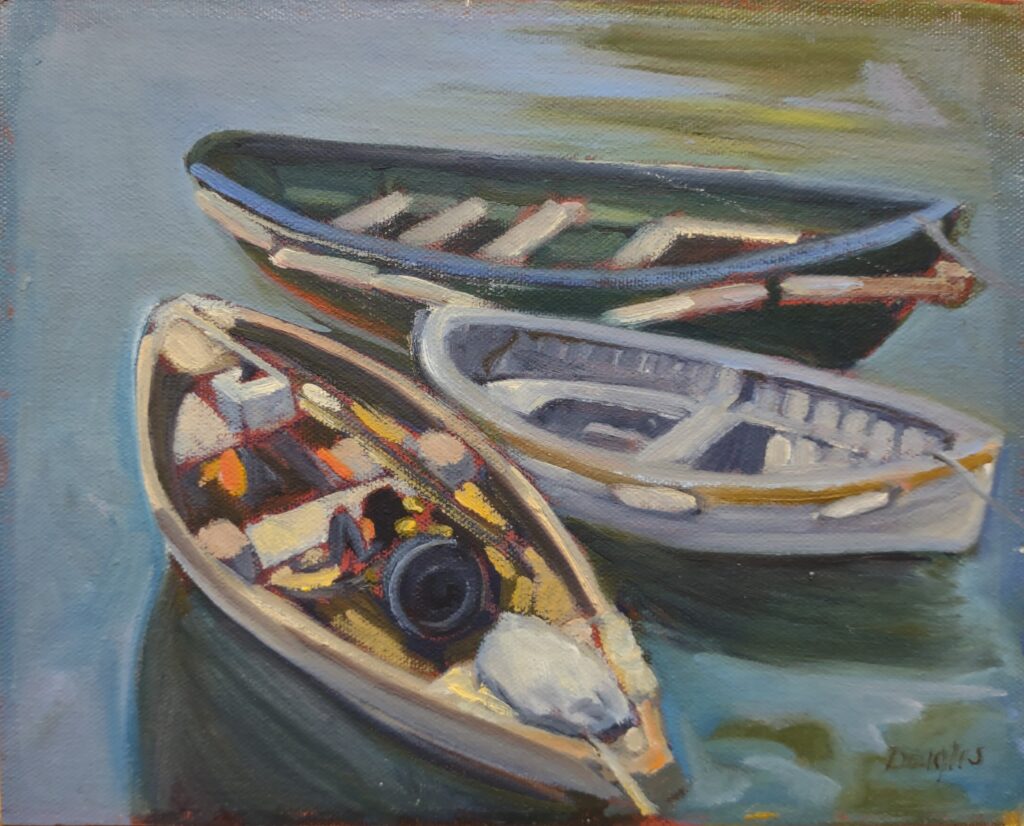

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

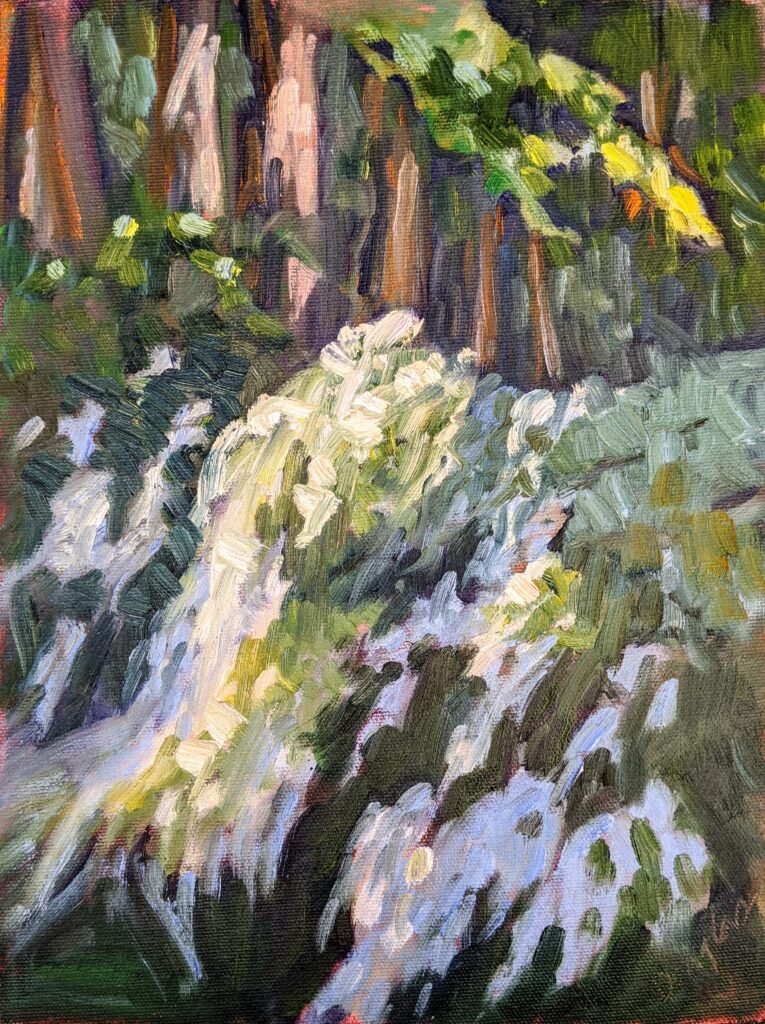

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.