Autumn has started its great transition; here are some tips to paint it in a believable way.

|

| Catskill Farm, pastel, by Carol L. Douglas. The light is definitely warm in Autumn, but the predominant landscape color is still green. |

In the northeast, soft maples start to turn orange and pink at the end of August. There are similar phase changes happening throughout the north. For example, in the Canadian west the aspens are starting to turn yellow-gold and the larches prepare to shed their needles.

The transition from summer green to November’s dun will take roughly ten weeks, but the daily changes are incremental.

|

| The Dugs, oil on canvas, by Carol L. Douglas. The earliest foliage change in the northeast is in the soft maples. |

Don’t delete the greens

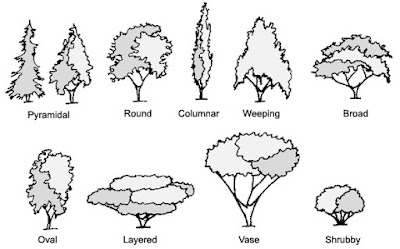

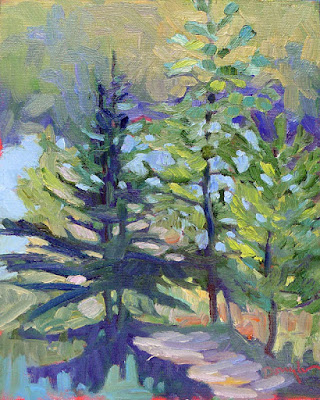

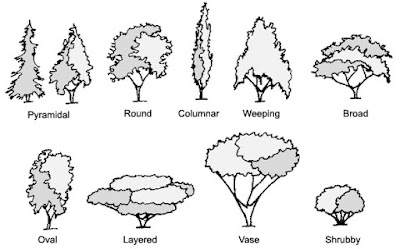

Until late fall, the predominant local color remains fairly cool: there is the blue of sky and water, and plenty of green leaves. Trees change at different rates. There are some that never change at all, but simply drop their leaves. Mowed grass remains green all year long. And, of course, there are evergreen spruces and pines.

|

| Adirondack Spring, by Carol L. Douglas. The same colors that appear in early spring return in the fall, but in a brassier way. |

There are far more colors than just red and gold

The same colors that appear in early spring foliage are repeated in autumn, but in a brassier way—reds, pinks, golds, chartreuse, teals, purples. In early fall, tinge the tops of trees with these hues; as the season progresses, they will become more dominant.

Know how trees change color

Where I live, the brilliant soft maples and ashes change first. Later, the oaks and beeches rattle mournfully in the wind. Each species has a characteristic color as well as a specific time to turn. Observe these changes, rather than just dashing color around.

|

| Glade, watercolor, by Carol L. Douglas. This painting is at the Jackson Memorial Library, Tenants Harbor, ME, through September. |

Pay attention to the understory

There are wildflowers blooming on the edges of fields—goldenrod, asters, blue chicory, and Queen Anne’s lace. These are less brilliant than their early-season counterparts, but the overall effect is a beautiful spangle against dried grasses. Meanwhile, hayfields are still bright green and there are apples in every hedgerow.

Underpaint the sky in last

When we put the sky in first, we have a tendency to paint it darker and brighter than it is. (That’s because of how our eyes respond to light.) It’s easy to then make the whole painting too dark.

That’s a great argument for the dark-to-light rule of oil painting, but what should watercolorists do? Start with a

monochrome value study, so you hit the blues properly the first time out.

How dark are the leaves?

Trees are often among the darkest features of the landscape, especially when we’re below them. But yellows and golds are naturally light colors. That makes us perceive fall foliage as lighter than it is. We need to take care to check the value of foliage in the design phase.

Avoid white in your foliage mixes, except to articulate a sun-struck passage. Darken yellow-gold with yellow ochre rather than with its complement, or you’ll kill the chroma. And check the leaf values against tree trunks; in some cases, they may not be that different.

|

| Keuka Vineyard, Carol L. Douglas, available through the Kelpie Gallery. This shows the earliest autumn changes, which in New York are in late August. |

How intense is fall color?

It’s easy to overstate the chroma in any season. It’s especially easy in autumn, because we’re responding to unusual brilliance. But Nature has a wide variety of chromatic intensities, from the delicate robin’s egg blue of a winter sky to the dazzling reflections off the ocean. There are plenty of greys in the landscape, especially in autumn.

There are other ways to convey the brilliance of autumn than to just use bright colors. Set the subject tree against more neutral tones, or place an intensely warm tone against a cool tone.

Autumn has its own color temperature

Above, I wrote that autumn colors were still predominantly blue and green. But the overall color temperature is warm, because the sun spends a lot more time on the horizon than it does in midsummer.

Autumn is known for its magical lambent light—the “season of mists and mellow fruitfulness/Close bosom friend of the maturing sun,” as John Keats said.

Color temperature is a lengthy subject, and I’ve written about it

here,

here,

here,

hereand

here(that’ll keep you out of the bars). The basic rule is that the color of the shadow is the complement of the color of the light. If light is golden, shadows are cool.

This was originally posted in September, 2019. Happy Labor Day, my friends!

Reserve your spot now for a workshop in 2025:

- Advanced Plein Air Painting, Rockport, ME, July 7-11, 2025.

- Sea and Sky at Acadia National Park, August 3-8, 2025.

- Find Your Authentic Voice in Plein Air, Berkshires, MA, August 11-15, 2025.

- Immersive In-Person Fall Workshop, Rockport, ME, October 6-10, 2025.