I spent a few extra days in Piseco last week. It was beautiful and austere in the silent falling snow. Shivering outside while painting in my nylon waterproof jacket and latex gloves, I spent more than a little bit of time considering the rigors experienced by Tom Thomson in the backwoods.

Thomson’s training was anything but conventional. He learned lettering and design in business school in

In 1909 Thomson joined the staff of Grip Ltd., where he came under the tutelage of the firm’s chief designer, J.E.H. MacDonald. MacDonald contributed much to Thomson’s artistic development: he himself was a formally-trained artist.

The McMichael Collection exhibits early works by Thomson and the Group of Seven and they are workmanlike but prosaic—typical landscape painting and graphic design of the period.

The radical change in their vision is partly attributed to a visit they made in 1913 to

But it also came from the land itself. In 1912, Thomson and his fellows began travelling to the Mississagi Forest Reserve and

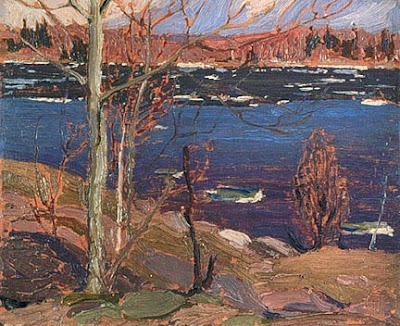

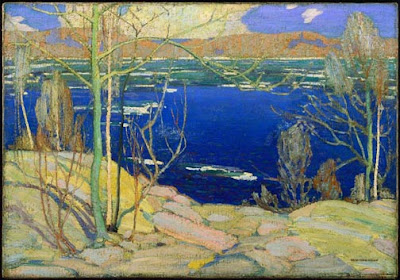

When painting on location, Thomson used a small wooden sketch box to carry his oil paints, palette, and brushes. His painting boards (generally about 9X12) were stowed in slots fitted in the top. This sketch box was similar to the modern pochade box except that it didn’t sit on an easel. Thomson worked sitting in his canoe, or on a handy log or rock with his sketchbox set in front of him.

Paintbox belonging to Barker Fairley, a disciple of the Group of Seven. Thomson’s would have been similar, for this was a kind of paintbox used until quite recently, when quick-release pochade boxes came into vogue.

In 1913 Thomson exhibited his first major canvas, A Northern Lake, at the Ontario Society of Artists exhibition. The provincial government purchased the canvas for $250, roughly equal to $5500 in current dollars. That year, Dr. James MacCallum guaranteed Thomson’s expenses for a year, allowing him to quit his job and head back to Algonquin. His career was made.

Thomson’s home base when he visited Algonquin was a small hotel called Mowat Lodge. He would stay at the Lodge in early spring and late fall, and then move into the woods when the lake and river ice broke up. In the depth of winter, he painted in his studio shack, a converted construction shed in a back lot in

Thomson was a certified guide, fire ranger, avid fisherman, expert canoeist, woodsman and painter—in short, a backwoods renaissance man. (Ironically, he was barred from enlisting in the Great War for health reasons.)

He was also plagued by self-doubt. AY

It was in the solitude of Algonquin’s lakes and woods that he discovered himself as a painter. The backwoods can be dangerous, and it’s also where he died.

Thomson died sometime between July 8 and July 16, 1917, when his body was found floating in

I have a canoe, a pochade box, and a fishing pole. The ice will be breaking up in a month or so… do I have a backwoods painting trip in me?