Our naked selves have always been with us, but the nude art model is a relatively new phenomenon.

|

|

The Toilet of Venus (The Rokeby Venus), 1644, Diego Velázquez, courtesy National Gallery of London. He painted at least three nudes despite the official disapproval of the Spanish crown.

|

Although ancient Egyptians wore a minimal amount of clothing, nudity in their art meant a defenseless state, often representing the dead or vanquished foes. The earliest reference to figure modeling is a legend about the fifth-century BC Greek painter, Zeuxis. It was said that he couldn’t find a woman beautiful enough to represent Helen of Troy, so he used features from five models. He is also reputed to have died of laughter after an older, wealthy patron insisted on modeling for Aphrodite. There is no doubt that the Greeks used real models; the courtesan Phryne modeled for Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos, the first life-size female nude in western art. Sadly, all these works are lost to us today.

The ancient Greeks also bequeathed us contrapposto, or counterpoise. This means the figure standing with most of its weight on one foot so that its shoulders and arms twist from the hips and legs.

|

|

Kritios Boy, c. 480 BC, is the first known example of contrapposto. Courtesy Acropolis Museum.

|

With the rise of Rome, art modeling disappeared in the west. It didn’t return until the late Renaissance. Michelangelo and Raphael started the study of the nude body. However, they didn’t intend to paint their models nude; they were just trying to understand the figure better for clothed painting.

In general, artists used their apprentices—always boys and young men—to model whatever figures they needed. There were exceptions, include Raphael, who made nude drawings of his mistress, and Lorenzo Lotto and Caravaggio, who used prostitutes as life models.

But in general, if non-apprentice models were used, they had a personal relationship to the artist. Many of these relationships are legendary: Rembrandtand his beloved Saskia, Botticelli and Simonetta Vespucci, Raphael and Margarita Luti. The working model, paid for his or her labors, did not yet exist.

The tension within Christendom about naked bodies was most extreme in the court of the art-loving Spanish King Philip IV, patron of Velázquez. Velázquez could paint the reclining Rokeby Venus under the king’s protection, because Philip owned many nudes himself. At the same time, painting or owning nudes—or even portraits in the fashionably-low necklines of the day—was officially discouraged.

In the 19th century, with the atelier system of training firmly established, professional artists’ models begin to appear. Olympe Pélissierwas a courtesan and model in Paris; she had been sold into sexual slavery twice as a teenage girl. Victorine Meurent (Édouard Manet’s Olympia) was a painter in her own right. Fanny Eaton was a Jamaican mixed-race charwoman who had a short, meteoric career modeling for the Pre-Raphaelites; her exotic features could represent a variety of characters. Fanny Cornforth was the model for, and mistress of, Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Cornforth’s career was indicative of a disturbing trend that continued into the 20th century. Earlier artists painted women with whom they were intimate; the new artists became intimate with women they painted.

|

|

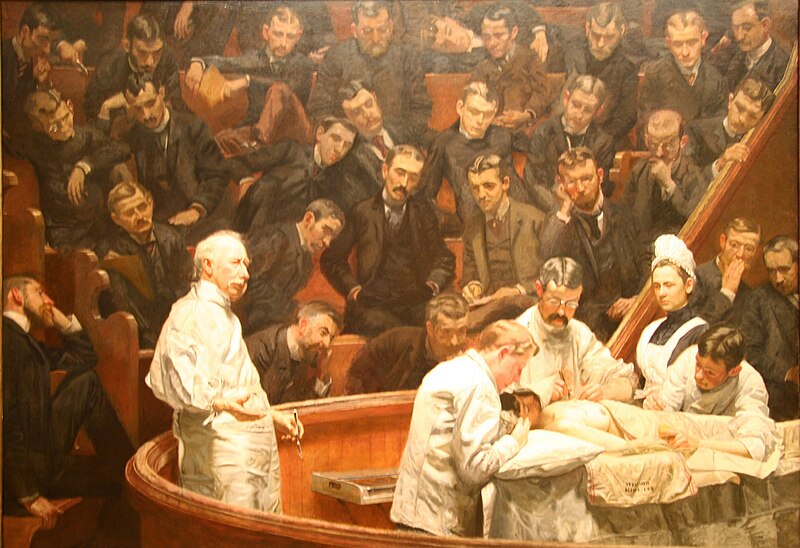

Study of a Seated Nude Woman Wearing a Mask, 1863-66, Thomas Eakins, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art. Modesty in Victorian ateliers was preserved by a mask for women and a loincloth for men.

|

Even as the need for figure and anatomy studies was publicly acknowledged, prudishness dictated that men wore loincloths and women had their faces covered while modeling. By 1886, Thomas Eakins had been teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy for ten years. He had transformed it into the leading art school in America.

In January 1886, lecturing about anatomy to a mixed-gender class, Eakins removed a loincloth from a male model so that he could trace the musculature of the pelvis (which supports the back and, in turn, the whole human body). He was forced to resign.

The 20th century brought a decline in figure painting as an art form, largely due to the decline of, historical and narrative painting. Still, drawing the human figure from life is considered a great way to learn draftsmanship. This is in part because the hierarchy of genres considered people more important than landscape or objects. It’s also because we have a connection to other people.

I’ll be teaching a class about modeling for the Knox County Art Society on Saturday, September 7. For more information, see here.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)