Despite predictions to the contrary, paintings and books haven’t been replaced by their digital analogs.

|

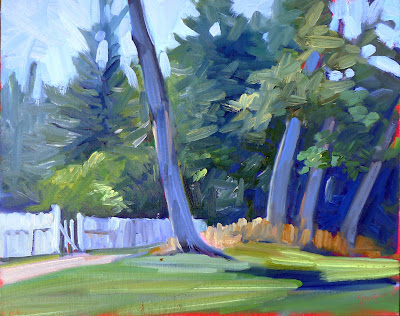

| Vineyard, Carol L. Douglas, 40X30, oil on canvas. |

Yesterday I heard from Sedona Arts Center that my workshop there is sold out. Schoodic and my first section in the Adirondacks are also sold out. (Of course, that still leaves a lot of options all over the country, so don’t imagine you’re free of me—yet.)

But it is part of a bigger trend, and one that points out my current dilemma: teaching is fundamentally limited by the instructor’s stamina and time. I can teach about seven six-week Zoom sessions a year, and they are usually full. Between them and my workshops, I can give one-on-one instruction to a maximum of 300 students a year. That’s if there are no returning students, which there always are. And that’s while maintaining a killer pace, one I’m unlikely to sustain for many more years.

|

| Tom Sawyer’s Fence, Carol L. Douglas, available. |

Teaching, as any person who’s done it can tell you, is very much a bespoke industry. It’s individual and personal. As I think about ways to reach larger audiences, I know that I will be sacrificing that intimacy in the process.

This blog started as an exercise in spreading instruction to a broader audience. By their nature, blogs are simply not well-organized or easy to search. Although I’ve covered everything you need to know in the fifteen years I’ve been writing, it takes good research skills to ferret out specific information, especially as I’ve shifted platforms a few times.

The downside of social media is that it has an incredibly short lifespan. As of 2021 it was estimated to be:

- Twitter: 15 minutes

- TikTok & Snapchat: Start decaying immediately unless viral

- Facebook: 6 hours

- Instagram: 48 hours

- LinkedIn: 24 hours

- YouTube: 20 days or more

- Pinterest: 4 months

- Blog Post: Over a year

That means few of us are getting past the headlines—or the advertisements. Some platforms, like Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn, are gatekeepers for more incisive writing, but most social media posts are simple snapshots.

|

| Bracken Fern, Carol L. Douglas, 9X12, oil on archival canvasboard |

Americans now overwhelmingly get their news from digital media. In a recent Pew survey, 65% of respondents said they rarely read printed news. At the same time, only 20% of Americans are willing to pay for online news. That means most of us are getting our information in some kind of recycled format. Ouch.

Magazines are doing slightly better, but are still in decline. Print subscription circulations have fallen by 7% over the past two years, while single-copy sales are down 11%. The exception is specialty magazines, dedicated to niche audiences.

|

| Best Buds, Carol L. Douglas, 11X14, oil on canvasboard |

On the other hand, industry watchers were confident that book publishing would be moribund by 2022, and that hasn’t happened. Books remain a $27 billion industry in 2022. That compares to e-books, at $3 billion and—weirdly—sliding. Clearly, people perversely cling to reading on paper.

For art books, paper remains the only way to go. I can’t imagine curling up with my phone and browsing a text on Wayne Thiebaud, for example. His luscious, thick paint looks great in life. It looks decent with modern printing technology; it disappears on my computer screen.

In the same way, there’s something about handmade art that cannot be replaced with digital analogs. People have lots of time for digital media—movies, snapshots, television and video—but when it comes to hanging fine art on their walls, they like the feeling of hand-craft. Total sales of art photography were just $80 million in an art market of $64 billion in 2019—and in decline. Despite 137 years of commercially-viable photography, painters and printmakers aren’t obsolete. I have a feeling it’s not going to happen.