Mark-making can be loose and gestural or very controlled. It’s personal, but it’s also something you can learn.

|

|

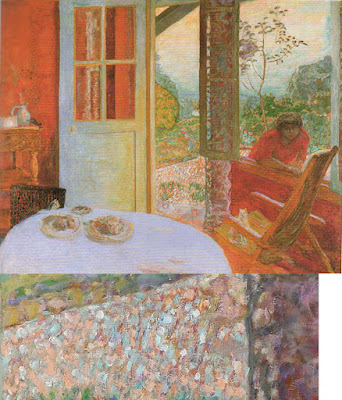

Dining Room in the Country, 1913, Pierre Bonnard, courtesy Minneapolis Institute of Art. Bonnard used small brush strokes, intense colors, and close values. |

Brushwork is, on one hand, the most personal of painting subjects. It’s also (especially in watercolor) highly technical. Much of what is called ‘style’ comes down to what brushes we choose and what marks we make with them. I wrote about that here.

Modern viewers are immediately captivated by bravura brushwork; it’s a sign of self-confidence and competence. It comes from lots of practice. It also must rest on a firm foundation of proper color mixing and drafting. Flailing around to fix something negates the freshness and decisiveness of good brushwork.

|

|

Wheatfield with Crows, 1890, Vincent van Gogh, courtesy Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. The motion in the painting is created by his brush strokes. |

The best, most immediate, brushwork lies on a foundation of careful planning. Continuous modification, glazing, changing color, etc., make for diffident marks.

Let’s talk about how not to do it:

- Unless you’re doing close detail, don’t hold your brush like a pencil. It’s a baton, and holding it to the back of the center-point (away from the ferrule) gives you more lyrical motion. Your grip can still be controlled by your thumb, you can hold it loosely, or even clutch it in your fist. The important thing is to let your arm and shoulder drive the movement of the brush, rather than just your wrist and hand. The farther back you hold the brush, the more scope of movement. To loosen up, blast some music and pretend you’re the conductor and that brush is your baton.

- Don’t dab. By this I mean a pouncing/stabbing motion with the tip of your brush. It’s amateurish in oils, anemic in acrylics, and hell on your brushes.

- Don’t use brush strokes that go in all one direction. Learn to apply paint in the round. This is a rule that can be broken, but make sure you’re doing so intentionally, not just because you don’t know how to paint in every direction.

- Don’t bury your line. Much of the power of Edgar Degas’ mature work comes from his powerful drawing; he was the most accurate draftsman of his age, and he let that stand prominently in his work.

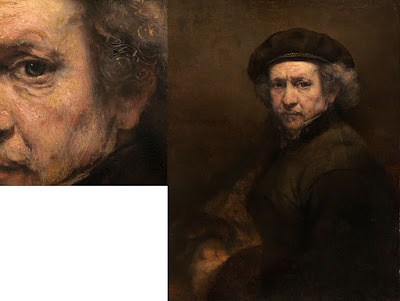

There are many painters whose brushwork I admire, but there’s little point in trying to copy them in my own work. Brushwork is as personal as handwriting. It’s where the artist expresses—or suppresses—his feelings. There’s value in attempting to copy passages by great painters, and I suggest you do so with the samples I’ve attached to this blog. But don’t try to paint like Sargent or Van Gogh or Rembrandt; use what you learn to create your own mature style.

|

|

Waterlilies, c. 1915, Claude Monet, courtesy Neue Pinakothek, Munich. Monet makes no attempt to hide his drawing in this painting. The brushstrokes are wet-over-dry. |

Style is the difference between our internal vision and what we’re capable of. We often don’t like our own brushwork when we lay it down; I think that’s because it’s too personal. Don’t continuously massage your brushstrokes hoping to make them more stylish. If the passage is accurate in color, line and precision, move on. You may come back to realize it’s wonderful.

|

|

Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, 1892, John Singer Sargent, courtesy Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh. Note that the transparent sleeves are not produced by glazing, but with direct, long brushstrokes. |

Use your brushwork to highlight the focal points in your painting. Sharp, clean, contrasting marks draw the eye, where soft, flowing, lyrical passages encourage us to move through. Let there be dry-brush texture and unfinished passages in your painting.