|

|

Carcass of Beef by Chaim Soutine, c.1924. This is part of a series that was painted in his apartment in Montparnasse, sans refrigeration.

|

Every art student knows Chaim Soutine’s Carcass of Beef series. Soutine—who didn’t always act as if both his oars were in the water—kept a beef carcass hanging in his studio to paint, bathing it daily in blood to keep it fresh. The stench drove his neighbors to call the flics. Soutine promptly lectured them on the importance of aesthetics over mere hygiene. At one point, the painter Marc Chagall saw the blood from the carcass leaking into the hallway outside Soutine’s room. He rushed out screaming, “Someone has killed Soutine!”

|

|

Rembrandt van Rijn’s Slaughtered Ox, 1655, was in the Louvre at the time Soutine painted his Carcassseries. Another version, very similar, is in Kelvingrove Art Gallery.

|

Soutine painted 10 works in his Carcass of Beef series. They were inspired by Rembrandt’s 1665 still life, Flayed Ox. The Christ-like aspects of Rembrandt’s steer carcass are often remarked on, but that probably reflects our modern separation from the slaughterhouse. We simply don’t see beef on the hook much anymore.

|

| The similarities to a crucifixion noted in Rembrandt’s paintings probably come from the reality of slaughtering beef. Modern beeves are split in half before hanging. |

I periodically buy a side of beef from a farmer in Niagara County, NY. I knew his grandfather, who farmed the same patch of land. The farmer has switched abattoirs to the one where we used to send our own steers back in the 1970s. It’s gone through two owners since then, so in a way I guess I knew the abattoir’s grandfather too. It’s still a small operation, but now it’s immaculate and odor-free.

|

| Beef aging in a modern abattoir. |

Either mid-century French beeves were a fraction of the size of modern American steers, or that old story about Soutine is flawed. The hanging weight of the steer we collected yesterday was just under 700 lbs. Soutine could not have humped that from the slaughterhouse up the stairs to his apartment. I doubt he could have paid for it unless it was already rancid, since he was perennially broke. A month-old Angus calf can weigh between 80 and 200 lbs., so I’m guessing those paintings should probably be called the Carcass of Veal series.

|

|

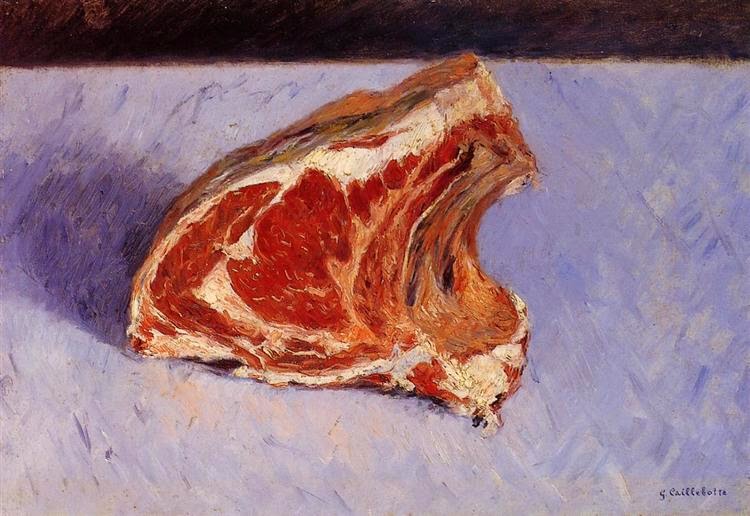

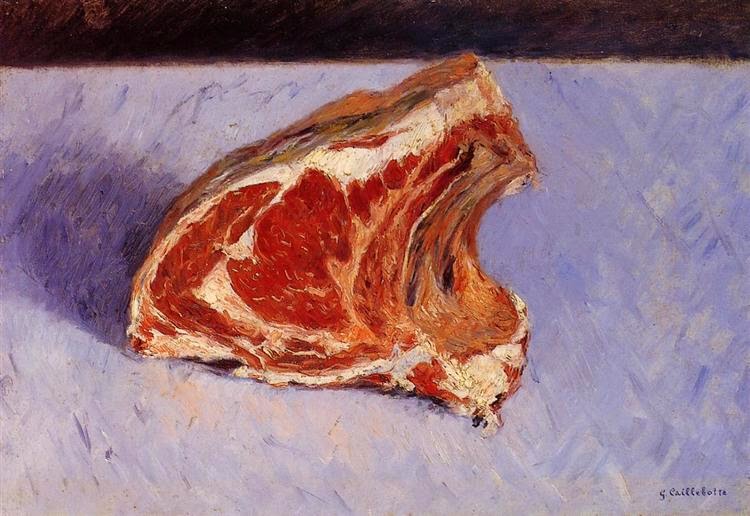

Gustave Caillebotte was an upper-class Parisian with an independent allowance. His Rib of Beef, 1882, is a much more sanitized affair.

|

I jumped at the opportunity to take a tour of the abattoir. We followed the workflow from the room where steers are stunned and killed, to the great coolers where they hang for a few weeks to age, to the newly installed smoker. The place was absolutely spotless. “When we kill a steer, we have both a veterinarian and a USDA meat inspector right here,” the butcher told me.

|

| The stamps are from the USDA inspector. |

Most of us eat meat but want to imagine that it originates in the plastic packaging in a grocery store. But there is nothing particularly revolting about a well-managed slaughterhouse. I am certainly more confident about a well-regulated abattoir in tiny Hartland, NY, than I am in the great slaughterhouses of the Midwest. And as a bonus, there are no plastic films, no Styrofoam trays, and no blister packs.

And, yes, I would jump at a chance to paint a hanging side of beef. They are beautiful, complex, corporeal, and colorful. Alas, the food inspectors would never allow it.

|

|

Lovis Corinth’s In the slaughterhouse, 1893, was painted during the first great reform movement of slaughterhouses.

|

Let me know if you’re interested in painting with me on the Schoodic Peninsula in beautiful Acadia National Park in 2015 or Rochester at any time. Click here for more information on my Maine workshops! Download a brochure here.