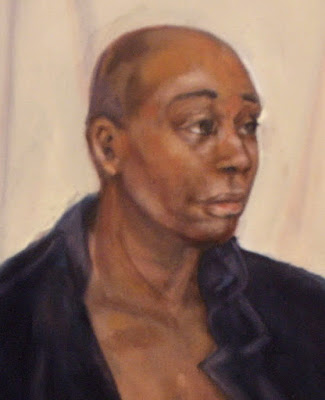

|

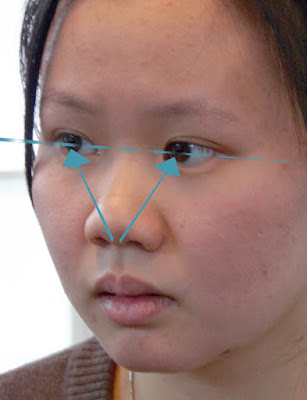

| Cece (who’s really being a good sport about these photos) starts by measuring her features and their positions. |

Almost every high school student who expresses an interest in going to art school is proficient at one thing: drawing from photographs. When I introduce them to the idea that they have to learn to draw from life, their reaction is always the same: they don’t want to do it because it’s hard.

Drawing is such a fundamental tool that every high school student should know how to do it, but they don’t. And this is true of kids from every high school, so I know it’s a general trend, not a problem specific to one place. (And, by the way, this is nothing new. In my public high school in the 1970s there were three art teachers, only one of whom taught traditional methods.)

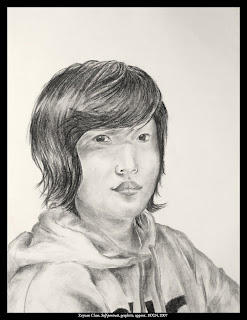

|

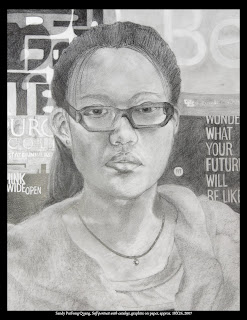

| It’s a good likeness but any competent reviewer is going to know she did it from a photo. |

The difference between a life drawing and a photographic drawing is something a trained artist can pick off at twenty paces. Life drawing is going to give kids an edge when it comes to portfolio review, and it’s going to make the transition to college easier. By the time I get them, most of these kids are already advanced enough to get into the college of their choice. My goal, therefore, has to be to help them get as much scholarship money as they can muster, because art school is expensive.

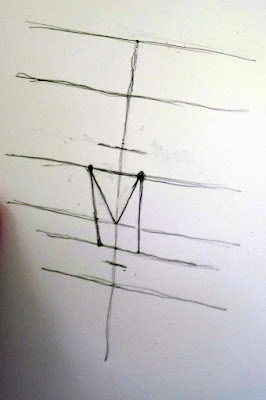

|

| Finally, the measurements are done and she can start working on the modeling. |

I have three high school seniors in my Saturday class, and they are currently doing an assignment they all loathe: a self-portrait done from a mirror. This requires that they suspend their idea of what they look like, which for all of us (but adolescents in particular) is a litany of things we don’t like about ourselves. It also forces them to use the first technique of drawing: measurement and angles.

We started this with practice drawings in charcoal. From here they go to carefully-rendered pencil drawings. I had hoped to work alongside them, since my ravaged old face hasn’t been immortalized in a while, but alas, I’ve been too busy.

I will be teaching in Acadia National Park next August. Message me if you want information about the coming year’s classes or this workshop.