This trip perfectly combined work and fun. How can I bring that attitude back to my regular routine?

|

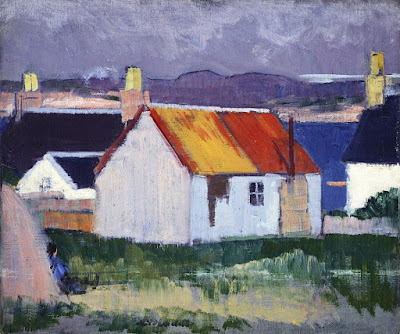

| White sand, by Carol L. Douglas. This is the best photo I’m going to have of this painting; it’s staying in Scotland. |

When plein airpainters stand in one place for a long time, we melt into the scenery. It’s a great job for eavesdropping. This week, I’ve heard chatter from all over the world. As I stood near the landing, I realized that visitors were coming off the ferry in national waves: Americans, then Scots, then Germans, then French-speakers. There are a lot of Americans in Scotland right now. The dollar is strong and Outlander has many die-hard fans.

Americans can be exuberant, but no more so than the Scots. I’ve gotten to hear bits and pieces of conversation I should never be privy to. You may feel as if you’re alone, but outdoors on a small island, there is always someone nearby.

|

| Daisy chain: a photo of a photographer photographing me painting something else. Courtesy of Douglas J. Perot. |

Because I’m part of the scenery, tourists take my picture while I’m painting. Occasionally they’ll ask, but that isn’t necessary. I’m outside in public, so I’m fair game. A few days ago, I posted the photo above on Instagram. “That is me! I hope you don’t mind I took some pics of you… How embarrassing!” wrote user surfeandovientos.

Let that be a lesson on the power of hashtags. People really do search and follow them.

|

| White sands of Iona, by Carol L. Douglas. The water is turquoise in Iona Sound. |

I generally get in my 10,000 steps a day. Even that is not enough to keep up with the typical middle-aged European. My friends and husband averaged 25,000 steps on their Iona ramble days. Even in town they walked to most destinations that we would grab a car for.

The average American walks 3,000 to 4,000 steps a day, or roughly 1.5 to 2 miles. If you don’t up your game significantly, you won’t enjoy visits to places like Iona, where there are few cars and roads. The time to start exercising is now, before you ever book a ticket.

You’re not getting as much value out of the scenery of your home country, either. The world looks very different on foot. Your heart, your soul, and the environment will all thank you if you start walking every day.

|

| Resting place of warriors and kings, incomplete, by Carol L. Douglas. |

I painted every day it wasn’t raining, and I still managed a decent daily ramble. I went to an auction preview, out to dinner, to Rosslyn Chapel, and traipsed around after my friends on one of the world’s most scenic golf courses. There were no golf carts; one had climb stiles over barbed-wire fencing and dodge the sheep to get from hole to hole. If golf was like that in the US, I’d find it irresistible.

“I know this is your opportunity to paint on Iona, but you don’t have to work all the time,” cautioned my husband. So I didn’t, merely keeping a pace that was comfortable. The challenge for me is to take that attitude into my summer season.

Yesterday, we moved along to Glasgow, where we walked through the city center before bed. I can’t really say I’ve ‘seen’ Glasgow, and I—sadly—missed the

Kelvingrove, but that’s the nature of travel: you always want to come back for more.

This morning I’ll repack my luggage and head to the airport and home. I have an appointment with the town assessor to look at our sewer connection first thing tomorrow morning. There’s nothing like returning to reality with a thump.