A long drive gave me plenty of time to ponder the meaning of success and failure.

|

|

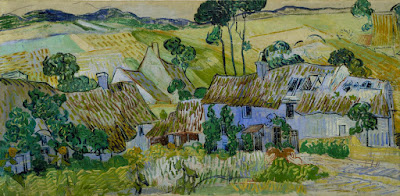

Whiteface Makes Its Own Weather, was painted last time I was here, in 2014.

|

Yesterday a radio host was talking about the late Dallas Cowboys football coach, Tom Landry, and his attitude toward losing. “It’s got a priority, but it’s not number one in my life. This creates for me a certain amount of calmness, even though I’m human enough to suffer when we lose,” Landry said.

I’d just been musing on artists’ reaction to failure. I’m as bad as anyone else about taking it personally. However, like Landry, my career isn’t my highest priority. That helps me regain my equanimity a little faster.

We sometimes think a single-minded focus on painting will make us better artists. If Landry’s career is any indication, that’s not true. In fact, it may hinder our recovery from failure. No matter what your walk in life, it’s never a question of whether you will encounter setbacks or crises. They happen to us all. The question is whether you will have the resilience to recover.

|

|

Weather Moving In At Barnum Bog, was painted last time I was here, in 2014.

|

I had a lot of time to think yesterday, as I was driving from Rockport, ME to Saranac Lake, NY. I had a choice of routes. I could drive cross-lots west, which was the shortest distance. Or I could head south to Manchester, which was the fastest route. The obstacle is Lake Champlain, which was in my way no matter which angle I come from. I chose the coastal route. Every town was a snarl of holiday traffic. The trip took hours longer than I anticipated. I was weary.

If New Hampshire and Vermont were starched and ironed, they’d be at least as big as Texas. They’re mountainous and beautiful and villainously difficult to drive.

At 4 PM I considered just stopping for the night and calling it quits. After all, the Green and White Mountains and the High Peaks of the Adirondacks are all Appalachian uplifts, and they all look more or less the same.

|

|

The Au Sable River at Jay, 12X9, was painted last time I was here, in 2014.

|

On the other hand, the stretch between Middlebury, VT and Lake Champlain is one long flash of brilliant green. Heading west from the Atlantic, it’s the first flat open farmland one sees. Those long fields, so common to the Midwest, don’t happen in the Northeast. Just beyond Lake Champlain, the High Peaks of the Adirondacks rise again, providing a mountain backdrop to a pastoral scene. Anyone interested in living back of beyond could do worse than to land in Addison County, VT.

Although we were instructed to do a nocturne once the sun set at 8 PM, I was impossibly tired. If one is going to be done, it will be an early-morning painting. The sun rises later here than it does on the Maine Coast.

Judging by this morning, I would have until 6 AM to finish. The Eastern Time Zone is impressively wide along our northern border. It runs from Eastport, ME nearly to Chicago. The difference feels substantial every time I come to New York. At this rate, the sun must come up around noon in Indianapolis.