The beautiful warmth of Wednesday was just a dream. It’s still April in Maine, and we all know April is the cruellest month.

|

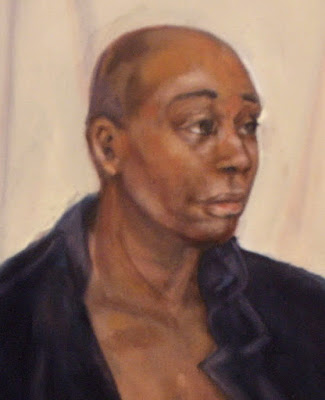

| Not done. |

On Wednesday, I met Peter Yesis and Ken DeWaard at Spruce Head. In the warm spring air, it felt like we were playing hooky. The neighborhood dogs trotted over to welcome us. There was a lobster boat on the pier, and the fisherman by the docks was working on his traps. Two Canada geese gamboled in the shallows. Perfect peace, and intimations of summer at long last.

I must have disconnected my common sense in the soft air, because I got there to realize I’d left my tripod at home. There are two absolute necessities for oil painting—an easel and white paint. Your other tools are helpful, but you can usually make a workaround solution. Forget your brushes? Take up palette-knife painting. Forget a canvas? One of your friends will have a spare.

|

| Not done. |

I improvised by putting my pochade box on a chair and balancing myself in front of it on Ken’s camp stool. It was wobbly but effective. However, Sandy Quang was meeting us after she stopped for a routine COVID test. The lab is near my house. She stopped by and collected my tripod.

I didn’t feel like grinding anything down to its final solution, so what I painted were sketches—sketches that can join the others sitting on my workbench in search of conclusion. Not that any of them need too much—a flourish here, a bit of light there. The overall structure is fine.

|

| Not done. |

Sandy peeled off in early afternoon, and then Peter left. I realized that I had to make the dump before it closed at 4 PM. Ken was starting his sixth sketch, but I was happy with my three, because I had all day Thursday before the weather closed in. I got the trash to the town dump with five minutes to spare.

Except, as so often happens, Thursday didn’t work out at all way I’d planned. I got to Rockport harbor, sat down and drew a composition I quite liked. Meanwhile, the boatyard crew was lowering a sloop into the water. I took a phone call while I waited to see where the boat would end up. “As soon as I start this painting in earnest, they’ll move that boat right into this slip,” I said. That’s always the way with boat paintings—they come and go.

|

| Not done. |

It turned out to not be a problem. This time I’d managed to leave my pochade box at home. By the time I drove home to get it, the tide had risen enough that my sketch was meaningless. Not to worry; the tide hits the same point four times a day. I’ll catch it on the flip side. Maybe by then the mast will be stepped on that beautiful winter visitor from Stonington, ME.

Later, I had some explanation for my absentmindedness. In the afternoon, I was laid low by a terrific headache and low-grade fever. I doubt it’s COVID, as I’ve had all my shots. I’m more concerned about Lyme, since I found a tick in my head after being in the Hudson Valley over the weekend. Yes, I’m calling my PCP. This is, sadly, routine in the northeast.

Meanwhile, we’re back to cold, dark and irritable weather. It won’t get out of the 30s today, and there’s snow on the forecast for New England. The beautiful warmth of Wednesday was just a dream. It’s still April in Maine, and we all know April is the cruellest month.