A teenage bully, a troubled artist, wealth, power, and a conspiracy of silence have created the myth of Van Gogh’s suicide.

|

|

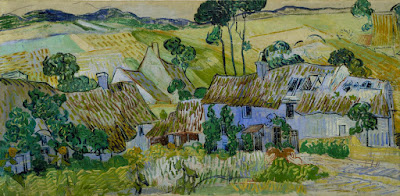

Farm near Auvers, 1890, Vincent Van Gogh, courtesy of the Tate

|

I stood for a moment catching my breath in Saranac Lake’s lovely old Beaux-ArtsTown Hall. A man sidled up, watching carefully to be sure we were utterly alone within the hubbub. He was reacting to last Thursday’s post.

“It’s been proven conclusively that Vincent Van Gogh was murdered,” he whispered.

Van Gogh’s suicide is legendary, so when biographers Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith questioned it in their 2012 biography, they were met with furious criticism. Some of their arguments don’t convince me. He left no note; not all suicides do. And anyone who’s had the misfortune to know a suicide knows that they can be simultaneously planning for the future and for their final exit.

|

|

The Church in Auvers-sur-Oise, View from the Chevet, 1890, Vincent Van Gogh, courtesy Musée d’Orsay

|

Other parts of their argument are more compelling. Shooting oneself in the gut is a painful and unlikely way to top oneself. Equally unlikely is staggering home over a mile of countryside to seek help.

If not Van Gogh himself, then who? Naifeh and Smith drew the bead on one René Secrétan, the 16-year-old son of a Paris pharmacist. He was a rich, privileged bully. Obsessed with Wild Bill Cody, he wandered around Auvers dressed in fringed buckskin, a cowboy hat and chaps, twirling a decrepit pistol. (And his neighbors called Van Gogh crazy.)

René cozied up to Van Gogh. He modelled for the artist, shared his porn stash and paid for drinks. He and his friends let the artist listen as they consorted with ‘dancing girls’. At the same time, René taunted and tormented Van Gogh.

|

|

The Road Menders, 1889, Vincent Van Gogh, courtesy the Phillips Collection

|

Van Gogh was shot on the road to the Secrétan villa, using René’s pistol. (“It worked when it wanted,” René joked.) Why wasn’t it investigated as a murder? Secrétan was the child of wealthy summer people, while Van Gogh was a dodgy weirdo. But he was also starting to be recognized as a painter. The suicide story was a neat cap on his legend, helping to create careers and drive up prices for his paintings.

Naifeh and Smith hired noted forensic expert Dr. Vincent Di Maioto analyze the records. They published the results in Vanity Fair.

|

|

Auvers Town Hall on 14 July 1890 (Bastille Day), Vincent Van Gogh, private collection. This was painted fifteen days before his death.

|

“It is my opinion that, in all medical probability, the wound incurred by Van Gogh was not self-inflicted. In other words, he did not shoot himself,” Di Maio wrote. As mystery fans might have expected, the gun was in the wrong hand.

The evidence for Secrétan’s guilt is there. But, as a curator at the Van Gogh museum wrote to Naifeh and Smith, “I think it would be like Vincent to protect the boys and take the ‘accident’ as an unexpected way out of his burdened life. But I think the biggest problem you’ll find after publishing your theory is that the suicide is more or less printed in the brains of past and present generations and has become a sort of self-evident truth. Vincent’s suicide has become the grand finale of the story of the martyr for art, it’s his crown of thorns.”