Marketing art is about being as visible and transparent as you can tolerate.

|

| Electric Glide, by Carol L. Douglas |

“Any thoughts you ever have on who might be interested in what I do, either gallery-wise, or direct buyer-wise, I’m all ears,” a reader commented on a recent post about finding your audience. I know this painter, but she lives in Colorado and I don’t know her market. I do know she’s already taking the first step I’d recommend: applying to plein airevents to get herself noticed.

What does ‘marketing’ mean?

- Getting your paintings seen by an audience;

- Keeping that audience engaged with your process via regular communication;

- Inviting them to your events.

Put that way, it’s not so daunting, is it? But expect to work half your workday at this marketing gig—first by studying how it works, and then by implementing what you’ve learned.

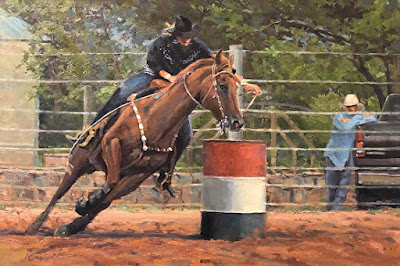

|

| Dry Wash, by Carol L. Douglas |

For example, although I’ve had an Instagram account for several years, I only recently figured out how it actually works. I learned that by listening to webinars and my friend

Bobbi Heath.

An artist can’t have too many friends. Often, the sale is less about what you know than who you know.

Still, can you talk comfortably about specific pieces of your work? Your inspiration and process? This self-knowledge is critical to selling your own work. Here’s a test: ask your best friend about what it is that you do all day. If he or she can’t answer, then maybe you need to start talking about your process more.

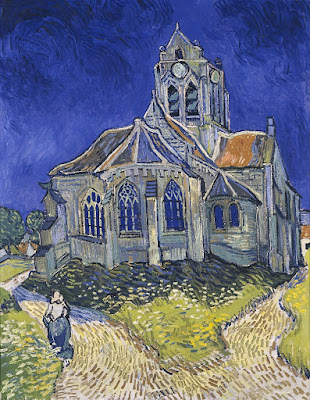

|

| Cape Elizabeth Cliffs, by Carol L. Douglas |

Everyone has an audience, and it started with your family. Just as your social circle grew in concentric circles from them, so too does your audience start with close friends and family. Your friends on Facebook and your followers on Instagram are your first audience. You need to connect with them regularly about your art. From that, your audience will grow as naturally as your circle of friends did when you were a child.

Your posts in all media should be designed to show a ‘whole’ you—not just your finished paintings. Your studio, your town, your brushes, your gaffes all combine for a total picture of you as an artist. Be as transparent as you have the nerve to be.

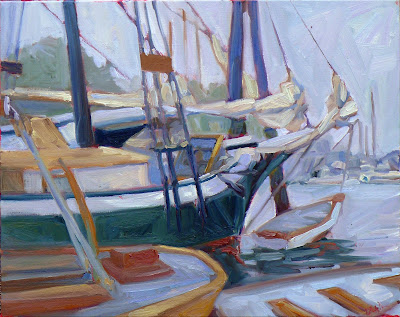

|

| Tricky Mary in a Pea Soup Fog, by Carol L. Douglas |

And update your website, or make one if you don’t already have one. That’s your business-card to the Web, and it must be as beautiful and inviting as you can make it. It doesn’t have to be exhaustive. It should include a bio/CV, artist statement, images of your work, and contact information.

Only then are you ready to approach a bricks-and-mortar gallery, because the first thing they’re going to do is look up who you are on the Internet.

As for what galleries you should approach, that requires legwork. Make a habit of visiting galleries in your area to check out the work they sell. Get to know the gallerists. Approach only those that seem like a good fit. And don’t be afraid of rejection; there are many reasons galleries won’t take you that have nothing to do with your work.

|

| Tom Sawyer’s Fence, by Carol L. Douglas |

At the beginning, I said that my reader is already applying for plein air shows. They’re a great way to be seen by a wider audience. So too are art festivals and juried shows. Apply to as many as you can tolerate.

Here’s a final bit of advice from my pal

Bruce McMillan: “I tell my students in my children’s book class that the way to deal with rejection when submitting a manuscript is to assume it’s going to be rejected. That way you’re never disappointed. And while it’s away, get the next place lined up that will reject it.”