We all know race is an artificial construct, yet we persist in using it anyway. It’s not even skin deep. It doesn’t exist at all.

|

| The Servant, Carol L. Douglas, is on display at the Rye Arts Center for the month of March. |

There is nothing that worries me more about the future of our democracy than Daylight Savings Time. It serves no practical purpose and disrupts our sleep schedules twice a year. Yet we can’t seem to get our corporate act in gear and rid of it.

I don’t just say that because I forgot to reset the clock on the coffee-maker last night.

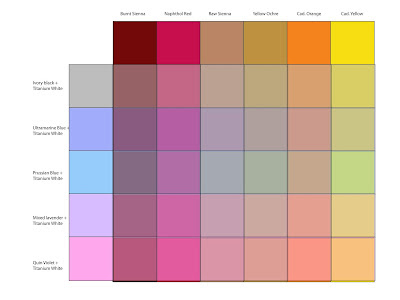

This week I’ll be teaching my classes to mix and use a variety of skin tones. The actual mixing is fairly simple; there’s a complete chart just below that will get you to every color you might need. It’s the application that’s so fascinating and difficult.

There are darker and lighter people, of course; to catch their color, just adjust the amount of white (or water) you use. There are also warmer and cooler skin tones. That’s why my chart has different rows. If your model is more olive, stick with a row that gives you more green tones. If pinker, choose a row that tends in that direction. You don’t need to mix all these colors for each model; it’s just a guide to set you in the right direction.

My original painted chart is ratty and worn but I also included it so you can see what the colors look like in paint rather than Adobe Illustrator.

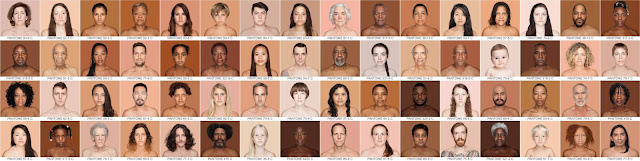

Natural light hitting the human skin is far more variable than we see indoors. We live (and paint) under artificial light. That narrows the color range dramatically, which is why painting the model under spotlights is poor practice. Photography also narrows the chromatic range of human skin. However, painting from life in natural light is not always possible.

There are greens, purples, and yellows in every person’s skin. The ears, face, fingers and toes all tend to pink; there’s blood closer to the surface. Some of us have visible traceries of blue veins. There are lovely greens and mauves in shadows. In fact, the only difference between my landscape palette and my studio palette is that red always makes an appearance inside.

|

|

Self-portrait at the age of 63 (detail) Rembrandt van Rijn, 1669, National Portrait Gallery |

Rembrandt was a master at capturing these subtle, varying colors in the human skin, as shown in the detail from his last self-portrait, above. He did this with the narrowest of palettes—essentially earth pigments with white. And yet he fools us into seeing a whole range of colors including blues and greens.

Rembrandt also painted Two African Men, below. Unfortunately, its surface is in such bad repair that it’s impossible to see what colors he saw in their skin. However, he would have used the same paints as he used in his own self-portrait. They’re all he had available.

|

|

Two African Men, 1661, Rembrandt van Rijn, courtesy Mauritshuis |

Our actual skin color is based on just one pigment, melanin. Lighter people just have more blue-white connective tissue and hemoglobin showing through.

We talk of Asians as having ‘yellow’ skin. That’s a modern lie. In the 13th century Travels of Marco Polo, the people of China are described as white. Eighteenth century missionaries also called Japanese and other East Asians white.

The ‘yellow’ label can be laid squarely at the feet of science. The father of modern taxonomy, Carl Linnaeus, first used the label fuscus (dark) to describe the skin color of Asians. Later, he began calling them luridus instead. That translates to ‘pale yellow’, ‘wan’, ‘sallow’, ‘lurid’—with a dash of ‘horrifying’ attached.

The father of comparative anatomy, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, used the word gilvus, which translates to ‘yellow’. (He’s also the guy who started calling Asians ‘Mongolians’.) By the nineteenth century, westerners were completely sold on the idea that Asians were yellow. Thanks, Science.

The farther down the Italian boot you go, the more you find genetic mixtures with Greeks, North Africans and Middle Easterners. That’s no surprise; the Mediterranean was the original melting pot. Southern Italians and Greeks are often very dark in color.

It’s no surprise that neither were considered quite white in 19th century America (although they had that designation for naturalization purposes). In fact the largest mass lynching in American history was of Italian-Americans. What’s more peculiar is that some people didn’t consider Irish-Americans white, either.

We all know race is an artificial construct, yet we persist in using it anyway. Paint-mixing shows us that the similarity in our coloration is far greater than the differences. Race isn’t skin-deep; it doesn’t exist at all.