|

| I found this while cleaning my room today, and somehow it seemed appropriate. I’m really big on making my students do self-portraits; maybe it caused Matt to become unhinged. |

As I mentioned earlier this week, Matt Menzies used to prattle on about my falling over a cliff at High Tor. For some reason, he committed it to writing this week. It’s so uncommon to read about one’s own death in advance, I felt I should share it with you. (But I take umbrage with his characterization of my beautiful blue Prius. It’s kind of otherworldly and angelic, that car.)

They were enigmatic times for the odd trio… Carol had all but shed her worldly ties, and confined herself to her studio exclusively. The only contact with the outside world she could stand was the occasional visits from her long-time friends, the in and out of her sharp-minded daughters, and of course, the company of Marilyn and me. Marilyn and Carol had worked together a long time, it seemed, and as the youngest and most inexperienced of the trio I feel I have an unbiased view. Some days the debates raged louder than all the pigments in the studio, and on others silence prevailed. It was Marilyn who could keep it the longest. She cultivated a contagious Zen, painting blissful blues and warm greens. Every image purred as a fuzzy cat beneath her hand: she was as a master could be, although she painted within a calm, simple joy, and not in a pursuit of some masterpiece.

But I digress: it was Carol who burned the midnight oil, studying and meditating on the nature of pigment, the subtle neutralizations, and the high chroma incidence. She possessed a perception unlike any other. I took to trying to see like she did. I would study her palette and duplicate it the best I could. When I asked for help, she would wander over to my painting, sometimes commenting on what was good or bad. With a palette knife in one hand and brush in the other, she would push me aside and scrape away my strokes, replacing them with her own without hesitation, as if to show me ‘the way it is to be done.’ I blended into her process well enough, like a lab tech working on a grand experiment.

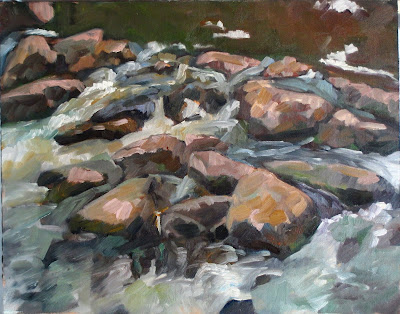

It was on such a day, at the end of an especially long and tiring season, that we took one of our outdoor plein air trips. Carol was fanatical in her search for the right angle, the right light. We loaded up the Prius (an awful dull light blue vehicle with the oddest angles) and we cruised down to the Southern Tier. The grey highway cut through and around the rolling green hills, and the deeper we went the higher the mountains rose. The day had blossomed into a drizzling overcast, but, we had come this far, and Carol’s foot continued to urge the car onward; Marilyn and I literally went along for the ride. As the Prius hauled up the mountain, I opened the window to breath in what I expected to be moist forest air, but as I leaned out I could feel nothing. The stillness was uncanny, and the raindrops barely tapped my face before evaporating back into the atmosphere. At times the sun seemed to work up the courage to break through, but then faded back into the cloudscape. Blue greens and grey blues permeated the landscape.

As we pulled to the crest overlooking a soggy valley, Carol stopped the car, looked back as if to indicate she had selected her spot, and proceeded to unceremoniously kill the engine. We all sat in silence for a moment, none of us particularly eager to step out into the moistened landscape, but we set to work and made good time in setting up. The painting proceeded for some time in silence, the drizzle dampening all sound and conversation. And as the water rained upon us, the tears rolled down our canvases. I wondered why they wept. My own sadness did not set in until much later in the day when the light began to fade. I concluded my work and I spun around in search of my betters. Marilyn was but a far-off speck on a neighboring hill, lost in a cloud so grey that it twinkled blue, but Carol…

Carol had set up on an adjacent crest, and I recalled looking over an hour or so before and seeing her facing far off into the distance, no doubt juxtaposing some specific tree with another hill line etc. But she was nowhere to be found. Her easel stood as a still as a deer in the fading twilight, an old rag hanging from it, motionless in the heavy air. As I approached I called out to her, with no reply. I looked down and around, and realized what must have happened. As the master stepped back paces to look at her day’s labor, almost complete, she must have backed to the cliff edge, lost her balance, and fell to her doom!

Marilyn had heard my shouts. I quickly ran in an arc but could deduce no other explanation. Dropping to my knees, I approached the cliff edge. I could see nothing but leaves and darkness. Marilyn arrived behind me, and as I peered up at her I knew that she knew what I had just learned. But there was no surprised look in her eye, and no sorrowful tears; only a calm acceptance, and a wise gaze. The grey-blue cloud loomed behind her and her silhouette glowed brown and orange in the fading sunlight. For a moment I thought maybe she had known of this event long before I had come over to investigate, long before this day had even arrived.

Not a word was spoken. We set to work folding the easels, carefully storing the paintings and supplies in the trunk. The gnarled rooted tree on Carol’s painting glistened with a vivid power, coiling upon itself, as if roaring atop the hill, gazing forward upon a valley it could never walk through. We closed the hood, and turned around to face the hilly crests one last time. As Marilyn paused and gazed for a moment too long I beckoned for her to come. “What for?” she called back. “Carol had the keys.”

At that realization the road seemed so much longer, and my way home impossibly far and full of obstacle. I was about to sink to the grass in despair, when Marilyn let out a quiet chuckle, and as I flicked my gaze over to her in confusion it erupted into laughter, and my confusion, my fear of this unknown life, was wiped away, to be replaced by a warm smile, and we began the hike down the mountain taking with us a final lesson from the old master.

Painting in Maine is definitely more interesting than falling off High Tor. If you’re interested in joining us for a fantastic time in mid-Coast Maine this summer, check here for more information. There’s still room in my workshops.