A painted value study is a great tool for understanding your subject.

|

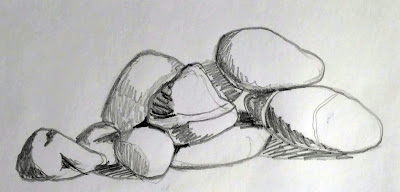

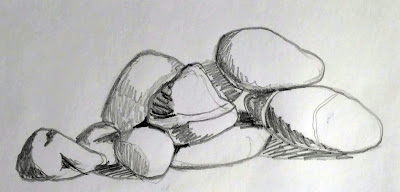

| Pile of rocks value study, by Jennifer Johnson |

Last week, I had you find and identify the simple shapes within a drawing. The prior week, we learned how to do abstracted value studies of our own homes. This week I want you to do a monochrome (black and white) painting based on a value drawing.

Jennifer Johnson is usually two steps ahead of me. At the end of Tuesday’s class she told me she’d done this assignment before I assigned it. She graciously offered her paintings to illustrate this post.

|

| Jennifer started by doing this meticulous, detailed drawing of her pile of stones. |

Before you can work successfully in color, you need to be able to work successfully in black and white. This is possibly the most valuable training an artist can give him or herself. I often do watercolor value studies before I paint in oils, but any painted medium will do for a monochrome study—gouache, watercolor, acrylic or oils. It is not necessary to use a pricey substrate for this exercise: gessoed paper is sufficient for acrylics and oils; use any paper you have for gouache or watercolor.

Jennifer was trying to teach herself about rock structure, so she set up a pile of stones. First, she drew a meticulous, careful drawing of her subject. This step is akin to research; you are learning the details of your subject.

|

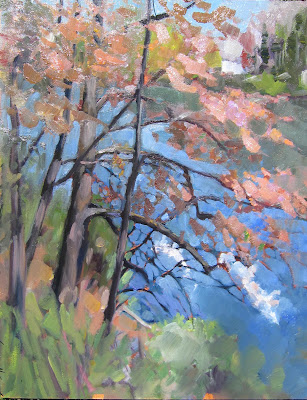

| She traced the basic shapes for each iteration. It saved her tons of time and made it easier to do multiple iterations of the same idea. |

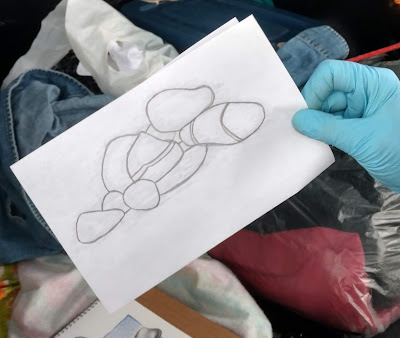

Next, she simplified and redrew her picture in graphite, focusing on the values, not the fine details. She then painted the rocks in monochrome acrylic. She added a final step, using five different colors to represent five different value levels. If you want to add this step, the exact colors you use are immaterial, but they should go from warm to cool or cool to warm as they get darker.

Jennifer used tracing paper to redraw her outlines. That’s perfectly fine, since she didn’t get hung up on the drawing. You may find yourself doing a half-dozen drawings before you get the levels and composition just right. Your goal isn’t to simply copy reality, but to design a construction that pleases your eye. It may be almost exactly what you see, or it may be very different.

|

| Next came a simple value sketch of the rocks. |

Value is the first and most important visual element available to the painter. Get it right, and you can be wrong about a lot of other things and still produce a stellar painting. It’s a lot easier to experiment with value when you’re not fussing about color management at the same time.

Why use paint instead of a pencil for your value study? In practice, many students have trouble applying different pencil tones to paper. They leave most of the paper white. Moreover, it’s hard to differentiate four or five value steps with a #2 pencil.

|

| In addition to her monochrome painting, Jennifer did a version where she assigned different colors to different values. If you do this, make sure the colors move warm-to-cool or cool-to-warm as they get darker or lighter. |

Work from light to dark. When you’re done, check where the area of highest contrast is. If that’s not where you wanted the focal point to be, you may have a design problem. If so, just do it again until your work can be read like a story: first focal point, next focal point, next focal point, etc.

Don’t be timid about laying in darks and don’t worry about neatness. This is rough work, and it should be done fast.

Why not do your value studies on the canvas you intend to work on? Once you cover it up, you no longer have it for reference. That becomes very important as the light shifts. Having a value study on hand can make the difference between being able to finish a painting or not.