|

| Tom Sawyer’s Fence, by Carol L. Douglas, oil on canvasboard. |

|

| Downdraft Snow by Carol L. Douglas is on exhibition at the Joseph A. Fiore Art Center this summer. |

|

| Marshall Point Rock Study, by Carol L. Douglas |

| Ottawa House, by Carol L. Douglas |

Watch Me Paint: World-Class Art, World-Class Instruction

|

| Tom Sawyer’s Fence, by Carol L. Douglas, oil on canvasboard. |

|

| Downdraft Snow by Carol L. Douglas is on exhibition at the Joseph A. Fiore Art Center this summer. |

|

| Marshall Point Rock Study, by Carol L. Douglas |

| Ottawa House, by Carol L. Douglas |

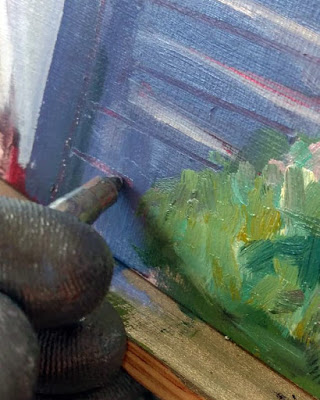

Brushes are ordinary; it’s what you can do with them that is extraordinary.

|

| Home Port, by Carol L. Douglas, 18X24, oil on linen. |

|

| What I was working on while painting with Ken DeWaard on Monday. Another day and I think I’ll be well on the way to finishing. |

|

|

Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight, 1500, Albrecht Dürer, courtesy Alte Pinakothek, Munich

|

|

|

Doge Leonardo Loredan, after 1501, Giovanni Bellini, National Gallery, London

|

|

| Perkins Point, by Carol L. Douglas. All the paintings in this post were done for Castine Plein Air last week. |

Often people ask me how we manage to get so many paintings done during an event. We avoid what my friend Brad Marshall called “flailing around.” That means those times when you seem to lose your way. We’ve all done it, when apparently everything we know falls out of our memory. I’ve written a simple protocol to avoid this. If you always work in this order, you’re less likely to flail around. Feel free to print this and tape it inside your paint box.

|

| Glacial erratic, by Carol L. Douglas |

1. Set up your palette with all colors out, organized in a rainbow pattern; may be done before going out.

|

| Lil’ Toot, by Carol L. Douglas |

|

| Tenney cottage, by Carol L. Douglas |

|

| Sunrise, by Carol L. Douglas |

|

| Water Street, by Carol L. Douglas |

| I spent most of my time yesterday moving the coffee table from place to place trying to make an interesting geometry of that bottom left corner. |

Mary Killen tells the story of Antony Armstrong-Jones (Lord Snowdon) and his lifelong enmity to Colin Tennant. It began when Armstrong-Jones was told to go to the tradesmen’s entrance while photographing Tennant’s wedding to Lady Anne Coke. The two men had been at Eton together.

|

| I’ve rearranged the furniture, set up my easel, and otherwise made a terrible mess of the drawing room. That’s a James Morrison landscape overlooking my shoulder there; a happy omen, if you ask me. |

|

| I captured my subject briefly for a quick drawing and managed to make her look all of fifteen years old. The bones are right, however, and I’ll try again today. |

It may seem like a fine brush is better, but that’s not true in wet-on-wet painting.

|

|

The Halve Maen passing Hudson Highlands, by Carol L. Douglas

|

|

|

Working backwards allows you to make clean edges without being overly fussy.

|

|

|

Start by getting rid of excess paint.

|

|

|

It’s easier to paint a line with a flat on its side than with a small round.

|

|

|

Then push the background color right up against the line.

|

|

| American Eagle in Dry Dock, by Carol L. Douglas |

| Camden harbor, by Carol L. Douglas |

Sometimes people ask me how we manage to get so many paintings done during an event. We avoid what my friend Brad Marshall called “flailing around.” That means those times when you seem to lose your way. We’ve all done it, when apparently everything we know falls out the bottom of our mind. I’ve written a simple protocol to avoid this. If you always work in this order, you’re less likely to flail around.

| Beach saplings, by Carol L. Douglas |

|

| Parrsboro sunrise, by Carol L. Douglas |

| Eastport harbor, by Carol L. Douglas |

|

Sea Fog on Main Street, by Carol L. Douglas. When painting plein air, you don’t have time to wait for the painting to dry to draw lines.

|

I’m working on a commission that has a lot of architectural detail. I don’t want the end result to be fussy. I’m not a clean renderer like Frank Costantino. He can drop a fine line with a rigger and it falls into the painting, cool and elegant.

|

| Working backwards allows you to make clean edges without being overly fussy. |

|

| Start by getting rid of excess paint. |

|

| The line going on with a bright. |

|

| It’s easier to paint a line with a flat on its side than with a small round. |

|

| Then push the background color right up against the line. |

|

| After two flags, a chair, and a lot of white trim, I was so cramped up by precision that I had to do this fast surf exercise to wash out my mind (and loosen up my hand). |

The best way to learn about your brushes is to experiment, but meanwhile, here’s a handy guide to oil painting brushes.

Above is a sable flat brush by Rosemary & Company. It can put down a very smooth surface and offers a lot of control, but it doesn’t carry the quantity of paint that an equivalent bristle brush will. I do have many sable brushes, but I save them for thin work in the studio.

This is a Robert Simmons Signet flat brush. The paint it lays down is both rougher and more impasto than the sable.

Flat brushes make an immediate, energetic mark. They’re excellent for fast, powerful surface work, long sweeping strokes, and blocking in shapes.

Used on their sides, they also make great lines, far more evenly than a small round can do.

Two rounds of very different sizes. A round is a more lyrical brush than a flat, and is a classic tool for painterly surface marks. It can be used to make lines that vary from thin to thick. A pointed round is used for fine detail. Bristle rounds tend to lose their points very quickly, however.

A bright is a less-flexible version of a flat. It’s great for short, powerful strokes or situations where you want a lot of control.

A fan brush probably has no place in a plein air kit, but I carry one anyway. I use it for blending, as on the left, although some people like using it to make whacked out marks as on the right. The problem is, it can carry very little paint, so its marks tend to be either gooey, as above, or very abrupt.

In my studio, I just use a clapped out soft-haired brush to blend.

| The float, by Carol L. Douglas. This is my first work out the gate at Joseph A. Fiore Art Center. I struggled with the aspect ratio. Is it done? Beats me. |

Last week I wrote about getting into galleries. The artist who prompted that post responded, “I would much rather discuss how I feel my work communicates the essence of wilderness and why it’s important to preserve wild places, than trying to convince them that I’m an accomplished painter and would be an asset to their gallery. I’d be much more comfortable discussing the importance of making sure people develop an appreciation for the wild places left on our planet, than the merits of my paintings.”

|

| My Mabef easel may nominally hold a 24×36 canvas, but in practice it’s too heavy. So it’s back to the Gloucester easel for oils. |

| Today I move over to Yupo and watercolor paper. |

| I was so taken by Yupo last month that I ordered twenty full sheets of it. Here’s hoping it works as well in that size. |

|

| Grain Elevators, by Carol L. Douglas, is an example of a cold-wax medium painting. I used it to add the rough texture of a beaten down industrial setting to the sky. |

|

|

The Sacrifice of Isaac, c. 1527, by Andrea del Sarto, courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art, shows a painting at the pre-glaze point.

|

|

|

The Sacrifice of Isaac, c. 1522, by Andrea del Sarto, courtesy of the Prado, shows the same subject in what del Sarto would have called its finished form, after meticulous glazing.

|

|

|

Self-portrait, c. 1655, Rembrandt van Rijn, courtesy Kunsthistorisches Museum. His technique involved painting impasto passages above transparent ones, or the opposite of glazing.

|