Today dories are an historical relic. When the Wyeths painted them, they were part of the saga of man and the sea.

|

|

Deep Cove Lobster Man, c 1938, N.C. Wyeth, oil, courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

|

What Bruce said that tripped my server was that the

catalogue, $45 from the museum gift store, was available for $24.50 from Amazon, including shipping. Even with his member discount, he saved $17, or 42%. I immediately ordered the same book and paid $28.49, because books aren’t always the same price on Amazon.

|

| Untitled, 1938, watercolor, Andrew Wyeth, sold at auction in 2017 |

That price difference is particularly noticeable in museum catalogues and fancy art books. I recently ordered an art text for my brother-in-law that was listed at over $200; he paid $24 for it. Because of this, I’ve learned to check my phone as I exit a show. Feel free to support an institution by paying a higher price in the gift shop, just be aware that you’re doing so.

|

The Lobsterman (The Doryman), 1944, N.C. Wyeth, egg tempera, courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

Bruce noted that the painting above, The Lobsterman (The Doryman), is “where people stopped and gazed longer than almost any other painting. There’s so much to see in its simplicity; it keeps people looking.”

This is one of five Maine dories I’m looking at today. All are by the first two Wyeths, père et fils, and all of the boats are occupied by people. The last image, Adrift, is almost funerary, and that points to the particular storytelling genius of the Wyeth clan. Was Andrew painting about the model or the working boat?

|

Adrift, 1982, Andrew Wyeth, egg tempera, private collection

|

“This is Walter Anderson, Andrew’s devilish friend since childhood, who his parents didn’t like Andrew associating with, who Ed Deci, former curator of the Monhegan Museum, considered a despicable crook, and who I knew when living on McGee Island, off Port Clyde for two years,” Bruce

wrote.

Andrew Wyeth was a young boy when he and his family first began summering in Maine. Andrew became friends with Walter and Douglas Anderson, son of a local hotel cook. Walt and Andrew became inseparable, and spent their days in a dory, exploring the coast and islands where locals fished. The two men remained friends for life. While Walt was clamming or otherwise ramshackling around, Andrew was painting.

|

|

Dark Harbor Fishermen, 1943, N.C. Wyeth, egg tempera, courtesy Portland Museum of Art

|

That’s the biggest difference between contemporary dory paintings and the Wyeths’ of nearly a century ago. They knew the boats and the men and boys who used them, intimately.

Before there were decent roads, working dories were the best way to move around coastal Maine. They were easily hauled up onto the beach. They could carry a few hundred pounds of fish or freight. From early settlement until mid-century, they were used as working boats, casually rowed (often standing) by working fishermen.

|

|

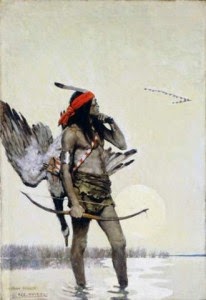

The Drowning, 1936, N.C. Wyeth, oil, courtesy Brandywine River Museum. This painting is in response to the drowning death of sixteen-year-old Douglas Anderson, who disappeared while lobstering. His body was found by his father and his younger brother, Walt.

|

Today they’re an historical relic, whereas to the Wyeths, they were part of the story of man and the sea. Dories today are divorced from their close association with working people. We paint them at their moorings, shimmering in the light, with no sense of the thin skin they once provided between the working fisherman and the cold, cold North Atlantic.