Your painting should be a carefully judged pas de deuxbetween reality and your own vision. That’s best worked out before you start adding a million different color variables.

|

| There are days when I just want to think compositionally, without any reality or detail cluttering up my mind. Monochrome is the best way I know to do this. |

I have a student who has started painting in monochrome as he learns to master color. It’s a great idea; I might insist on it, except it would result in revolution. People love ‘color’ but fail to see that value is color’s anchor. However one expresses darks, their pattern is what drives a painting. It’s best seen in monochrome, before you add in hues.

By removing the hue question, Mark is doing the equivalent of practicing one hand of his difficult piano sonata at a time. It’s a time-honored technique because it works.

|

|

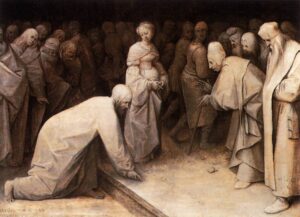

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery, 1565, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, courtesy the Courtauld Gallery |

A grisaille (pronounced ‘griz-EYE’) is a painting done entirely in shades of grey or another neutral. It can take the form of an underpainting or can be a finished painting in itself. It’s not generally done in lieu of a pencil sketch or notan, but rather as a discrete step in the process of planning a painting.

It is possible to start a painting with just hash-marks on the canvas. Some excellent painters do this; however, for the beginner, that’s the circus trapeze without a net.

Historically, grisaille has been used for finished works of art. This was particularly true in decorative painting, where grisaille might serve as a sort of trompe l’oeilfor sculptural relief. Paint, even in the hands of a master, is cheaper than marble.

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery, above, was a personal painting owned by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his descendants. It’s tiny, roughly 9X12. Its character and intimacy are enhanced by being in monochrome. In that way, it has the feel of a fine drawing.

|

|

Odalisque in Grisaille, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and his workshop, 1823-24, courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art |

Sometimes popular paintings were copied in monochrome to simplify life for engravers. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ copy of his La Grande Odalisque, above, is one such example. There lies a lesson for students: if engravers, who are skilled artisans in their own right, find it difficult to track value, how much harder is it for new painters?

Mostly, grisaille has been done as underpainting. Until the Impressionists, with a few exceptions, painting was done in what is called ‘indirect painting.’ Paint was applied in thin layers, or glazes. The underpainting was laid down in a thinned form, usually (but not always) in monochrome. This layer also served to tone the canvas. After it dried, subsequent thin washes of color were worked over the top. The underpainting was allowed to mingle with the glaze colors. It’s a powerful technique, but not as lyrical or free as alla prima painting.

|

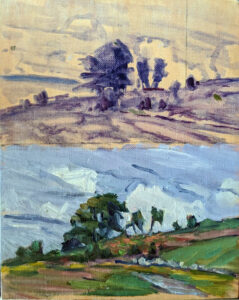

| A small underpainting grisaille example I made for my students. |

Alla prima doesn’t really require any underpainting, but it’s an act of incredible courage to just start daubing on a blank canvas. Few artists are that brave—or foolhardy, depending on how you look at it. So, we tend to do exactly the same thing as our predecessors—a thin wash of paint, usually in grisaille, that tells us where stuff is supposed to go. Of course, we must learn to judge that first wash to a nicety. Too stiff, and the underpainting is too thick. Too goopy, and everything above it turns to soup.

If the composition reads well at this value-study phase, the painting is almost always going to work, providing you stick with your plan. If it doesn’t, you’re unlikely to salvage it.

All value judgments are subjective. There’s no reliable way to measure the value of a color. The camera is as subjective as the human eye. Your painting should be a carefully judged pas de deux between reality and your own vision. That’s best worked out before you start adding a million different variables in the form of hues.