Fabric is an opportunity to support the composition with line and shape, and insert abstract design into even the most hyper-realistic paintings.

| Underwear and glass head, by Carol L. Douglas. |

Every artist needs to be able to paint fabric, either to clothe his subjects or to support a still life. Drapery used to be an important element of art instruction; now, in the age of denim and t-shirts, it’s often an afterthought in figure classes.

It deserves more attention. It can be the most flexible element in a painting. The flow and rhythm of drapery are an opportunity to support the composition with line and shape. Fabric is a place to insert abstraction in even the most hyper-realistic paintings.

If you’ve never painted fabric before, keep it simple at first. Stay away from black in your first exercise; Bronzino and his pals might have made it look easy, but they had a lot of practice. Your composition can include an object as a focal point, or you can just concentrate on the fabric itself.

I find it easier to paint drapery with my glasses off, because it’s really a question of getting the values and shapes right. Details (if there are any) are almost irrelevant.

Start with shapes

|

|

Drapery for a Seated Figure, c. 1472, Leonardo da Vinci, courtesy the Louvre |

Leonardo da Vinci did the above study of drapery as preparation for a painting he completed around the age of twenty; he continued to draw drapery throughout his life. That was the norm for the Renaissance artist, and it’s something we can learn from.

The good news is that you can practice drawing drapery almost anywhere. People are always dropping jackets over chairs. I did years of these sketches in church.

|

| I drew my mittens in church about ten years ago. Boy, have they stretched out since then. |

The individual shapes within folds and shadows are irregular and arresting, but they must be accurate and properly measured or the whole picture will be off. This is much easier to realize with charcoal or graphite then in paint. Drapery is one area where a quick value study is not sufficient—if you draw the shapes properly, then the painting will flow almost as an afterthought.

Don’t overstate the value shifts

|

| The Laborer Resting, by Carol L. Douglas, has matte, shiny and lacy fabrics. |

Fabric can be highly reflective, as in a silk taffeta, or very matte. The difference is in the contrast range. Taffeta has deeper shadows and lighter highlights than linen. You must get these right for the fabric to be plausible. You can achieve this by premixing paints (in oils) or with a good monochrome study (in watercolors).

The darkest folds may not be much darker than the mid-tones, but they can have significantly different color. Fabric reflects on itself; the highest chroma is often within folds and shadows.

In oils, start by blocking in the large shapes in the proper values. This will be easy if your drawing is good and a nightmare if you skimped on that phase. In oils you can lay down the shapes without regard to edges; in watercolor you’re going to have to paint the edges accurately from the beginning.

| Teenage boy sleeping in church, by Carol L. Douglas. You can almost always find a drapery study to sketch wherever you are. |

Most of the edges in draperies are soft

Blending is oil paint’s greatest strength, and you can block in your whole drapery study before going back with a dry brush and softening the edges. If you overblend, just repaint that passage.

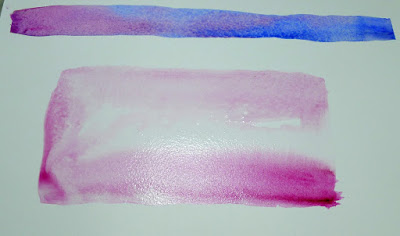

In watercolor, the soft edges must be painted properly from the beginning. If both sides of a shape are soft, use a wet-in-wet technique. If one side of the shape needs a hard edge and the other a soft one, you can soften the edge right after you’ve applied the paint. The amount of water needed is critical, and the technique requires practice.