If you have room for a cup of coffee, you have room to paint.

|

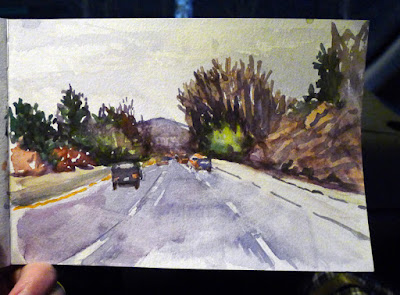

| I finished this sketch as the sun finally set. |

I painted across Canada (the first time) in a corner of an overloaded Suzuki Grand Vitara containing four people and all my daughter’s earthly belongings. Compared to that, the passenger seat of my Prius is downright spacious.

You will need a plastic cup, water, a small watercolor kit and a watercolor sketchbook. That will all fit in a roomy pocket or a purse.

|

| You should be carrying water when you drive. The plastic cup is just a refinement. |

“But the scene is constantly changing!” you say, and you’re right. You’re going to generalize rather than draw a specific moment on the road. This teaches us about composition and reducing our paintings to their essentials.

You can’t paint while driving, any more than you can text. (I would think this goes without saying, but apparently there is no idea so bad that someone won’t try it.) This is why I ended up doing this painting on I-495 instead of on scenic Route 1. It was my turn to drive during the interesting parts.

|

| This was the road I chose to demonstrate this technique. Not a Scenic Byway. |

I-495 is a contender for America’s most boring road, except when traffic stops and it becomes one of our most irritating roads. Yesterday, its monotony was compounded by a gloomy sky, the tail end of last week’s Nor’easter. There’s a lesson in that: you can find beauty anywhere, if you look for it.

I start car paintings by studying the passing scene. What is the line or motif that is most commonly repeated? In some cases, it’s the pitch and roll of the hills. In others, it’s the way farm buildings sprawl down hillsides.

|

| A generalization of the passing scene. |

Usually, I look out the side window, at about the point where old cars used to have vent windows with little cranks. That gives you a view of something other than the road, while still being comfortable.

However, in eastern Massachusetts the trees grow right up to the verge. You must look forward, straight down the road. The dominant motif is the stands of trees, and the question is how they interrupt the skyline. There are occasional hills in the distance, and there are other cars.

This was the point when I realized I left my pencil on my dining room table. It’s easily replaced, but not on a freeway on a Sunday evening. Miraculously, we stopped at a rest stop and parked next to a pencil stuck in the mud. Cleaned up, it was perfectly serviceable.

|

| Some light washes in place. I would normally use a different brush, but I want to demonstrate that this can all be done with a kit that fits in a pocket. |

I needed that pencil, because I always start with a line drawing incorporating those iconic features of the landscape. A light wash established the drear of the sky and the hill in the distance. I used the tiny brush from my field kit to make the point that you don’t need a lot of tools for this. This brush is great for fine lines, but it doesn’t make good washes. I laid it on its side and scumbled the grey sky in instead. If I were using a juicier brush, I’d have run the sky below the tree line.

Every watercolor painting needs a test sheet, because watercolor is all about density control. Luckily, you can test on the reverse of a prior page. It won’t hurt the painting on the other side. Or, if you want to conserve paper, stick a loose sheet in there and move it around as you need it.

|

| You always need a test sheet, even when you’re messing around. |

When it comes to observing details, the repetitiveness of the freeway helps. When I need a stand of spruces, there is always one more just up the road. There are dormant, deciduous trees everywhere, and Massachusetts has no shortage of rocks.

Of course, you’re not going to paint fine lines unless you’re stopped in a traffic jam. The roads in the northeast are too jarring for that. Thus, my taillights are just a suggestion, dripped onto the paper at the last minute. I finished just as the last light faded from the sky.

|

| St. Elias Mountain Range, Yukon Territory, painted from a car in 2015. |

This is a technique you can use to amuse yourself anywhere you have at least 40 minutes to kill—in a car, a train, on a plane. It’s the basis of our sketchbook technique for our

Age of Sail workshop, except we’ll be concentrating on water instead of pavement. Of course, Penobscot Bay is also much prettier than a Massachusetts turnpike.

I’m on the road to Alabama and points west this week. Tonight’s destination is the lovely Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. Stay tuned to this spot to follow my travels. (Or subscribe above; it’s probably easier.)